Stopping COVID-19

Emory researchers embark on an epic journey to tackle humanity’s big test

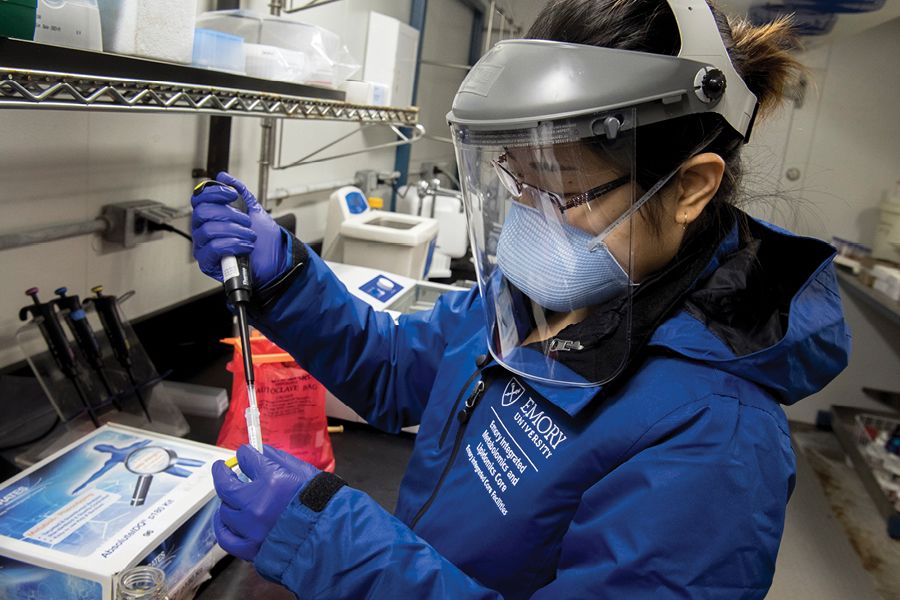

Dr. Aneesh Mehta at Emory University Hospital

Dr. Aneesh Mehta at Emory University Hospital

Dr. Aneesh Mehta stood in the still hallway outside the hospital room where his patient lay dying.

Just days earlier, Mehta had discussed treatment options with the vital and alert elderly businessman who came in with COVID-19. The patient was interested in Emory’s clinical trial of the antiviral remdesivir, which Mehta was leading.

Now he was in intensive care at Emory University Hospital, having taken a rapid turn for the worse. His only companion was a nurse in full protective gear. She held his smartphone in one hand. On the line, his family was saying goodbye, their grief playing out in a room far away. Mehta watched as the man’s granddaughter told stories of their life together. It was unclear if the man, who was heavily sedated, understood. He stopped breathing soon after.

Even months later, Mehta gets emotional as he recalls that day in April. An infectious disease doctor and researcher who cut his teeth during the Ebola outbreak, Mehta has seen his share of death. But to watch a man die without his loved ones at his bedside was wrenching.

“No one wants to see a patient die. What is heartbreaking about COVID-19 is that so many patients are dying and they are dying alone,” Mehta says.

It also crystallized for Mehta what was at stake. The final trial results for remdesivir, which had failed for this patient, turned out to be so promising that top infectious disease expert Dr. Anthony Fauci hailed it as the new standard of care. It became the first treatment for COVID-19 approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“It shows that what we do scientifically and medically has a tremendous impact,” Mehta says. “This is research being done to save the lives of our patients in our hospitals right now. This is why we are here.”

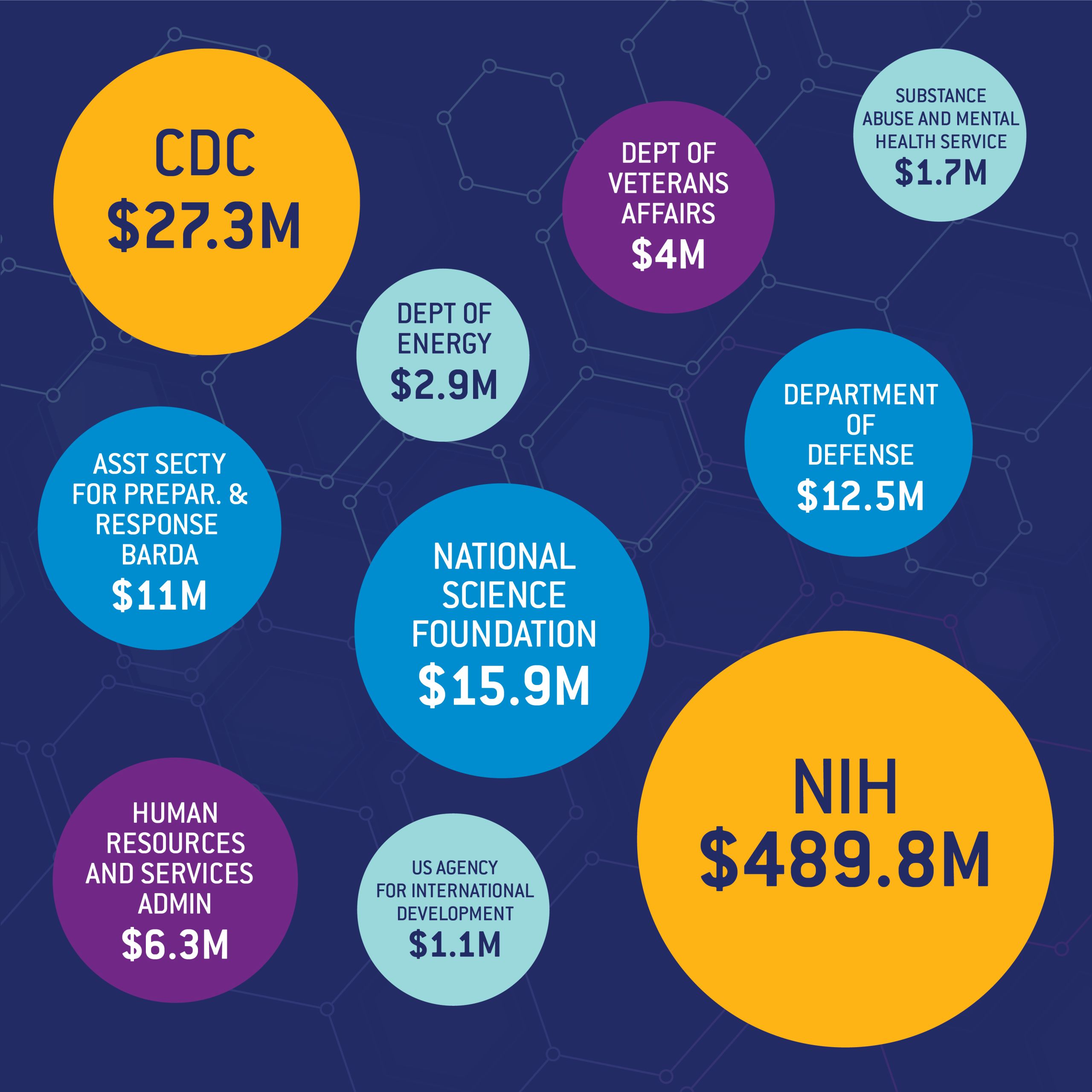

Since the pandemic began, federal funding agencies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have ramped up their support, entrusting academic research institutions such as Emory to do what they do best: help solve big challenges.

In response, Emory mobilized its discovery enterprise to safely and quickly accelerate research, emerging as a national leader in coronavirus-related research; in a span of months, its investigators had launched 177 studies, including more than 30 clinical trials, and published more than 350 papers on COVID-19.

When the fiscal year closed at the end of August, Emory had earned a record $831 million in research funding. More than 10 percent of the total ($88.3 million) was for COVID-19 research, a testament to the ability of researchers to shift course rapidly to tackle the world’s biggest public health crisis in more than a hundred years.

Record year for research funding

Funding totals by source: fiscal year 2020

Funding totals by source: fiscal year 2020

“In my short time at Emory, I’ve been deeply impressed by the dedication of our researchers and clinicians, whose cutting-edge discoveries are opening new pathways of understanding in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Emory’s record research funding this year reflects well upon not only their expertise, but the trust they have earned in helping to meet the greatest global health challenges.”

—Gregory L. Fenves, Emory president

“At a time of great uncertainty, our researchers, staff, and clinicians are responding with grit, courage, and compassion. They are working day and night to improve lives and provide hope through the development of new vaccines and by discovering new ways to diagnose and treat people with COVID-19.”

—Dr. Jonathan S. Lewin, executive vice president for health affairs, Emory University; executive director for Woodruff Health Sciences Center; and CEO and chair of the board, Emory Healthcare

The Emory difference

A culture of collaboration and nimbleness

COVID-19 trained a spotlight on what Emory has long done well: Research with impact.

Soon after the pandemic swept the country, biomedical research found itself confined to a select few labs at Emory. Researchers pivoted, shifting their expertise and resources toward fighting an unprecedented threat in a variety of ways. For instance:

- Specialty experts such as Dr. Denise Jamieson, chair of gynecology and obstetrics, joined colleagues across the country to develop national guidelines for pregnant women with COVID-19.

- Virologist Dr. Mehul Suthar and immunologist Dr. Jens Wrammert took on the ambitious task of understanding immunity among those infected with SARS-CoV-2. One strand of their research looks at the durability of immunity—in other words, could those who were once infected be reinfected? How long will protection provided by a vaccine last?

- Rheumatologist Dr. Ignacio Sanz and colleagues shifted gears from studying autoimmune diseases to severe COVID-19. They identified similar activation patterns as they had seen in lupus, which has possible implications for survivors with recurring “long-haul” symptoms.

- Oncologists at Emory who had experience with radiation treatment or studying graft-versus-host disease adapted their therapies to tamp down COVID-19 inflammation.

Groundwork for successful COVID-19 research was laid a long time ago

Emory’s deep background in HIV research paved the way for an experimental COVID-19 treatment, illustrating how life-saving research sometimes happens. It began with virologist Dr. Raymond Schinazi, who had a theory that anti-inflammatory drugs being tested for HIV could help COVID-19 patients. He and his team partnered with infectious disease specialist Dr. Vince Marconi, who tried out the experimental therapy at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs hospital—with encouraging results. The collaboration between these two researchers from different disciplines, combined with their external partnerships and associations, sowed the seeds for the drug’s inclusion in a federally sponsored nationwide clinical trial. How? Watch the video below.

COVID-19 and beyond

2020’s brightest moments for research faculty

“This research funding milestone is a wonderful tribute to our faculty and staff and demonstrates the confidence our peers and funding agencies have in Emory’s ability to generate impactful research even under extraordinary pressures. Infectious diseases research continues to be a jewel in Emory’s crown, and I am proud of the richness of our diverse research portfolio that spans many disciplines from health sciences to environmental studies to the arts and humanities.”

—Deborah Bruner, senior vice president for research, Emory University

Click on the images below to see what a few of our brightest minds were up to in fiscal year 2020.

Nichole Phillips | Theologian

Nichole Phillips has long been fascinated by the convergence of science and religion, and is now helping to lead a sweeping new study exploring that complicated nexus. Working with a few congregations in Atlanta, Phillips is drawing on the legacy of social traumas—such as the Tuskegee syphilis study—to understand how scientific beliefs and attitudes shape religious identity.

"There’s not much research at the intersection of religion and science when it comes to Black faith practitioners. I’m bringing in cultural memory studies to focus on social and cultural traumas and how they may be transferred generationally and impact the way people think. This is all so relevant now as we look at the disparities of COVID-19."

Nichole Phillips is associate professor in the Practice of Sociology of Religion and Culture at Candler School of Theology.

Nichole Phillips | Theologian

Nichole Phillips has long been fascinated by the convergence of science and religion, and is now helping to lead a sweeping new study exploring that complicated nexus. Working with a few congregations in Atlanta, Phillips is drawing on the legacy of social traumas—such as the Tuskegee syphilis study—to understand how scientific beliefs and attitudes shape religious identity.

"There’s not much research at the intersection of religion and science when it comes to Black faith practitioners. I’m bringing in cultural memory studies to focus on social and cultural traumas and how they may be transferred generationally and impact the way people think. This is all so relevant now as we look at the disparities of COVID-19."

Nichole Phillips is associate professor in the Practice of Sociology of Religion and Culture at Candler School of Theology.

Susan Margulies | Biomedical engineer

For Susan Margulies, 2020 has been a momentous year; she was inducted into both the National Academy of Engineering and the National Academy of Medicine. The work of Margulies in biomedical engineering has focused on injuries to the lungs and the brain where she has pioneered new ways to look at cause and effect in vexing problems. Margulies leads a joint department at Georgia Tech and Emory that is consistently ranked among the top in the nation.

"In each of my fields, there has been an 'aha moment' when a hypothesis that once seemed outlandish in the scientific community is accepted. That is deeply rewarding."

Susan Margulies is the Wallace H. Coulter chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University.

Susan Margulies | Biomedical engineer

For Susan Margulies, 2020 has been a momentous year; she was inducted into both the National Academy of Engineering and the National Academy of Medicine. The work of Margulies in biomedical engineering has focused on injuries to the lungs and the brain where she has pioneered new ways to look at cause and effect in vexing problems. Margulies leads a joint department at Georgia Tech and Emory that is consistently ranked among the top in the nation.

"In each of my fields, there has been an 'aha moment' when a hypothesis that once seemed outlandish in the scientific community is accepted. That is deeply rewarding."

Susan Margulies is the Wallace H. Coulter chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University.

Wilbur Lam | Pediatric hematologist and bioengineer

Dr. Wilbur Lam seems to be everywhere. When he’s not seeing patients, he’s co-developing a new app to detect anemia or helping to lead a team of researchers vetting COVID-19 diagnostic tests for a $50 million federally funded initiative. Lam’s lab explores new ways that microtechnology can diagnose and treat blood disorders, cancer, and childhood diseases.

"Academia has a reputation for being slow. But, from a research perspective, it can be super nimble. If you have the right people and if you have the right place with the right amount of resources, like Emory, you can ask and answer almost any scientific question."

Wilbur Lam is an associate professor at the School of Medicine and at the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University. He is also affiliated with the Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

Wilbur Lam | Pediatric hematologist and bioengineer

Dr. Wilbur Lam seems to be everywhere. When he’s not seeing patients, he’s co-developing a new app to detect anemia or helping to lead a team of researchers vetting COVID-19 diagnostic tests for a $50 million federally funded initiative. Lam’s lab explores new ways that microtechnology can diagnose and treat blood disorders, cancer, and childhood diseases.

"Academia has a reputation for being slow. But, from a research perspective, it can be super nimble. If you have the right people and if you have the right place with the right amount of resources, like Emory, you can ask and answer almost any scientific question."

Wilbur Lam is an associate professor at the School of Medicine and at the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University. He is also affiliated with the Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

Jericho Brown | Poet and writer

Jericho Brown challenged the rules of poetry by drawing deeply on its traditional forms. His creation—the duplex—blends the rigor of a sonnet and the repetition of the ghazal with the flavor of the blues. In awarding Brown’s most recent work, The Tradition, the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, jurors labeled it “a collection of masterful lyrics that combine delicacy with historical urgency in their loving evocation of bodies vulnerable to hostility and violence.”

"For poets and other writers, research becomes a way of looking at the history of all things and taking them down to the scale of one so that people can have access."

Jericho Brown is the Charles Howard Candler Professor of English and creative writing and director of the Creative Writing Program in Emory College of Arts and Sciences.

Jericho Brown | Poet and writer

Jericho Brown challenged the rules of poetry by drawing deeply on its traditional forms. His creation—the duplex—blends the rigor of a sonnet and the repetition of the ghazal with the flavor of the blues. In awarding Brown’s most recent work, The Tradition, the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, jurors labeled it “a collection of masterful lyrics that combine delicacy with historical urgency in their loving evocation of bodies vulnerable to hostility and violence.”

"For poets and other writers, research becomes a way of looking at the history of all things and taking them down to the scale of one so that people can have access."

Jericho Brown is the Charles Howard Candler Professor of English and creative writing and director of the Creative Writing Program in Emory College of Arts and Sciences.

Sarah Finch | Doctoral student

What if talking to your smart speaker felt like talking to a friend? That’s the goal of Sarah Finch, whose research focuses on the juncture of technology and natural language. Working with faculty adviser Jinho Choi, Finch and her team of fellow Emory students used artificial intelligence to create “Emora,” a social chatbot able to carry on a conversation with warmth and personality. The team won this year’s Alexa Prize sponsored by Amazon.

"Dialogue is innately human. We don’t want to talk to a robot and think ‘I’m talking to a robot.’ It’s very stiff and very unnatural and not warm and welcoming. We’re trying to capture what talking to your friend or family member feels like to you. It feels supportive and welcoming and like you want to come back and do it again."

Sarah Finch is a PhD student at Laney Graduate School in the Department of Computer Science and Informatics.

Sarah Finch | Doctoral student

What if talking to your smart speaker felt like talking to a friend? That’s the goal of Sarah Finch, whose research focuses on the juncture of technology and natural language. Working with faculty adviser Jinho Choi, Finch and her team of fellow Emory students used artificial intelligence to create “Emora,” a social chatbot able to carry on a conversation with warmth and personality. The team won this year’s Alexa Prize sponsored by Amazon.

"Dialogue is innately human. We don’t want to talk to a robot and think ‘I’m talking to a robot.’ It’s very stiff and very unnatural and not warm and welcoming. We’re trying to capture what talking to your friend or family member feels like to you. It feels supportive and welcoming and like you want to come back and do it again."

Sarah Finch is a PhD student at Laney Graduate School in the Department of Computer Science and Informatics.

Victoria Pak | Translational research scientist

The average person will spend about a third of their life sleeping. Victoria Pak is exploring how disturbances in sleep may predict negative health outcomes. Her current research is focused on understanding the mechanisms of sleepiness in individuals with sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease.

"My passion for research and commitment to health promotion drives my scientific exploration. Throughout my work, I strive to improve sleep and the quality of life of individuals and families."

Victoria Pak is an assistant professor at the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

Victoria Pak | Translational research scientist

The average person will spend about a third of their life sleeping. Victoria Pak is exploring how disturbances in sleep may predict negative health outcomes. Her current research is focused on understanding the mechanisms of sleepiness in individuals with sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease.

"My passion for research and commitment to health promotion drives my scientific exploration. Throughout my work, I strive to improve sleep and the quality of life of individuals and families."

Victoria Pak is an assistant professor at the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

Aneesh Mehta | Infectious diseases specialist

For many patients hospitalized with COVID-19, the drug remdesivir is now the standard of care. And Dr. Aneesh Mehta is part of the reason why. Under Mehta’s leadership, Emory enrolled more participants than any site around the globe in a clinical trial of the antiviral. Mehta is now investigating how the drug works when paired with other drugs, including a powerful anti-inflammatory.

"This isn’t research that’s being done to answer some abstract, obscure, or esoteric question. This is research being done to save the lives of our patients in our hospitals right now."

Aneesh Mehta is associate professor at the School of Medicine and chief of infectious diseases services at Emory University Hospital and Emory University Orthopaedics & Spine Hospital.

Aneesh Mehta | Infectious diseases specialist

For many patients hospitalized with COVID-19, the drug remdesivir is now the standard of care. And Dr. Aneesh Mehta is part of the reason why. Under Mehta’s leadership, Emory enrolled more participants than any site around the globe in a clinical trial of the antiviral. Mehta is now investigating how the drug works when paired with other drugs, including a powerful anti-inflammatory.

"This isn’t research that’s being done to answer some abstract, obscure, or esoteric question. This is research being done to save the lives of our patients in our hospitals right now."

Aneesh Mehta is associate professor at the School of Medicine and chief of infectious diseases services at Emory University Hospital and Emory University Orthopaedics & Spine Hospital.

Allan Levey | Neurologist

For more than three decades, Dr. Allan Levey has worked to decode the mysteries of Alzheimer’s. Now, he says, major breakthroughs in both treating and diagnosing the disease may be imminent. Levey—and Emory—are again at the forefront, leading a new $37 million international program to accelerate the development of promising new therapies. In the future, Levey says, a blood test could determine who’s at risk of developing Alzheimer’s and then preventative treatment could begin to head it off.

“There’s no such thing as failure, in my view. Failure is a vital and inevitable part of scientific success. Progress is born from failure and motivates us to continue the discovery process.”

Allan Levey chairs the Department of Neurology at the School of Medicine and is director of the Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

Allan Levey | Neurologist

For more than three decades, Dr. Allan Levey has worked to decode the mysteries of Alzheimer’s. Now, he says, major breakthroughs in both treating and diagnosing the disease may be imminent. Levey—and Emory—are again at the forefront, leading a new $37 million international program to accelerate the development of promising new therapies. In the future, Levey says, a blood test could determine who’s at risk of developing Alzheimer’s and then preventative treatment could begin to head it off.

“There’s no such thing as failure, in my view. Failure is a vital and inevitable part of scientific success. Progress is born from failure and motivates us to continue the discovery process.”

Allan Levey chairs the Department of Neurology at the School of Medicine and is director of the Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

Samuel Sober | Neurobiologist

When Samuel Sober wanted to understand how the brain controls muscle movement, he turned to finches. This year, a journey that began by exploring how songbirds learn to sing resulted in the creation of an Emory-led international consortium studying the mysteries of motor control. The research, funded with a $2.5 million grant from the Simons Foundation, could eventually help those suffering from neural system injuries.

"The goal is to understand how the brain controls the body through all these incredibly precise movements. And then the question becomes, what can you do with that? That’s an exciting question."

Samuel Sober is associate professor in the Department of Biology in Emory College of Arts and Sciences.

Samuel Sober | Neurobiologist

When Samuel Sober wanted to understand how the brain controls muscle movement, he turned to finches. This year, a journey that began by exploring how songbirds learn to sing resulted in the creation of an Emory-led international consortium studying the mysteries of motor control. The research, funded with a $2.5 million grant from the Simons Foundation, could eventually help those suffering from neural system injuries.

"The goal is to understand how the brain controls the body through all these incredibly precise movements. And then the question becomes, what can you do with that? That’s an exciting question."

Samuel Sober is associate professor in the Department of Biology in Emory College of Arts and Sciences.

Madhav Dhodapkar | Immunologist

Dr. Madhav Dhodapkar doesn’t just want to treat multiple myeloma. He wants to cure it or prevent it altogether. The immunobiologist and his team are investigating promising new cell therapies for the blood cancer that kills more than 12,000 people a year. Dhodapkar believes lessons from this research could help other cancers as well.

"When I started in this field, an average myeloma patient used to live only a couple years. Now it’s common for our patents to live six to eight years after diagnosis. Some live 15-plus years. That’s the reward of seeing this develop."

Madhav Dhodapkar is a professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at the School of Medicine and is director of the Center for Cancer Immunology at Winship Cancer Institute.

Madhav Dhodapkar | Immunologist

Dr. Madhav Dhodapkar doesn’t just want to treat multiple myeloma. He wants to cure it or prevent it altogether. The immunobiologist and his team are investigating promising new cell therapies for the blood cancer that kills more than 12,000 people a year. Dhodapkar believes lessons from this research could help other cancers as well.

"When I started in this field, an average myeloma patient used to live only a couple years. Now it’s common for our patents to live six to eight years after diagnosis. Some live 15-plus years. That’s the reward of seeing this develop."

Madhav Dhodapkar is a professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at the School of Medicine and is director of the Center for Cancer Immunology at Winship Cancer Institute.

Dabney P. Evans | Public health leader

The research of Dabney Evans lives at the intersection of public health and human rights. Her work leading a new partnership to end sex trafficking in Atlanta focuses on girls and women of color as well as the trans community. Evans is also investigating whether COVID-19 has led to increases in domestic violence.

"Most of the work I have done deals with stigmatized issues—difficult and challenging issues. Wicked problems. But these are the things that fascinate me and are the knots that I want to untangle."

Dabney Evans is an associate professor in the Hubert Department of Global Health at the Rollins School of Public Health.

Dabney P. Evans | Public health leader

The research of Dabney Evans lives at the intersection of public health and human rights. Her work leading a new partnership to end sex trafficking in Atlanta focuses on girls and women of color as well as the trans community. Evans is also investigating whether COVID-19 has led to increases in domestic violence.

"Most of the work I have done deals with stigmatized issues—difficult and challenging issues. Wicked problems. But these are the things that fascinate me and are the knots that I want to untangle."

Dabney Evans is an associate professor in the Hubert Department of Global Health at the Rollins School of Public Health.

What’s next:

Finding answers to six big COVID-19 questions

1. How do we prevent COVID-19 transmission?

Public health experts agree that while nonpharmaceutical measures may reduce transmission, only effective vaccines will help end the pandemic.

In March, a record-short 66 days after the coronavirus’s genetic sequence was first published, Emory was one of two sites to begin testing the first COVID-19 vaccine in the United States. The vaccine, which uses a new mRNA approach, harnesses the body’s own cells to produce SARS-CoV-2 viral spike proteins. That Phase I trial , led at Emory by investigators Dr. Nadine Rouphael and Dr. Evan Anderson, has since progressed to an advanced-stage efficacy study that has completed enrollment nationwide. Preliminary results released by the company are encouraging.

“Having this trial take place at Emory gives Atlanta-area residents the opportunity to participate in a study that, if successful, has the potential to help stem the tide of this disease,” says Anderson, who has also advocated for accelerating clinical trials for vaccines in children.

Emory is also testing a single-dose vaccine candidate in a Phase 3 trial. Additionally, researchers at Emory are in the middle of developing a vaccine that is currently being evaluated in animal models. Apart from vaccines, Emory investigators are also studying therapeutics as preventive agents and antiviral antibodies in high-risk environments, such as nursing homes.

2. What can we learn from modeling disease transmission and super-spreading events?

Governments around the world are discussing how to ensure people’s safety while lifting lockdown restrictions. Emory public health researchers Ben Lopman and Samuel Jenness are on the trail for answers. They are looking at how people interact to understand how educational, work, and leisure spaces should modify practices.

“Given that we’re often presented with two extremes—where we do nothing or we completely shut society down—the interesting scientific question is, where do we find that middle ground?” Jenness says.

He and Lopman adapted a model that simulated COVID-19 transmission on university campuses. They used the tool a few months ago to help Emory safely reopen for its fall semester.

A phenomenon seen in COVID-19 is the ability of a tiny number of infected people to spread the disease to a much larger group. Lopman and another colleague, Max Lau, studied what are known as “super-spreaders” in Georgia using data from the state’s department of health. They found that 2 percent of symptomatic COVID-19 cases appeared to be responsible for 20 percent of new infections during spring.

The study found that younger people seemed to be the main drivers of super-spreading events. The results indicated that maintaining social distancing is crucial and curtailing super-spreading events will be essential to control the pandemic.

3. How long does immunity to SARS-CoV-2 last?

News reports in summer 2020 conveyed some anxiety over this issue: how fast does immunity drop off after SARS-CoV-2 infection? Levels of antibodies do decline after an acute infection has passed but Emory experts say this is normal – it is how the immune system de-escalates to avoid injury to the body.

Still, a quick decline could set limits on what levels of protection a vaccine could achieve and how long it could last. To answer these questions in a detailed and comprehensive way, Emory Vaccine Center director Rafi Ahmed along with researchers Jens Wrammert and Mehul Suthar will look at both antibody levels and memory B and T cells, the reserves for reengaging the antiviral immune response, over the next two years.

They have teamed up with their counterparts at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. Their goal is to have 500 participants from the Seattle and Atlanta areas— all COVID-19- confirmed, with a mix of milder, nonhospitalized and more severe hospitalized cases.

4. How many people have been exposed to the virus?

In early summer 2020, the United States was not even close to “herd immunity.” About 3 percent of first-time blood donors had antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, according to the American Red Cross. Later estimates put exposure in some areas of the country at more than 10 percent.

For a more definitive answer to this question, we can look to studies such as Emory’s COVID-Vu, a nationwide, population-based study using antibody and virus tests taken at home. In June, Emory public health researchers Aaron Siegler and Patrick Sullivan received a $6.6 million grant to launch the study, which is designed to sample everyone, whether they are sick or not.

Soon after receiving the award, the COVID-Vu team began mailing out test kits, reporting a few months ago that 15,000 test kits had already been sent. Once the researchers have gauged how response rates vary geographically and among different demographic groups, they will adjust to ensure that the study looks at the population proportionally.

The surveillance data will help public health agencies better understand how the virus is spreading through the population over time. The antibody test results will also provide information about previous infections in people who may have been asymptomatic.

5. What type of tests are accurate, quick, and easy to administer?

Fast, affordable, and accurate testing is crucial to help treat, isolate, or hospitalize people who are infected with COVID-19. Access to rapid and reliable testing remains important for containing the spread.

Emory and partners are playing a leading role on this front as part of a national initiative supported by more than $50 million in federal funding.

In a three-phase vetting process that includes a Shark Tank-style competition, biomedical engineer and pediatrician Dr. Wilbur Lam and his colleagues at the NIH-funded Atlanta Center for Microsystems Engineered Point-of-Care Technologies are evaluating hundreds of diagnostic products for COVID-19 submitted by private companies. The eventual goal is to provide millions of accurate and easy-to-use COVID-19 tests available for at home or other point-of-care use as early as this winter.

Lam, critical care specialist Dr. Greg Martin, and Georgia Tech nano-engineer Oliver Brand and their team have been assessing hundreds of tests; some resemble pregnancy kits, with specimen swab, reagents, and test strip combined into a single tube. Others are more Star Trek tricorder-like, capable of providing results with a hand-held machine in 30 minutes. Emory was involved in evaluating most of the tests chosen by the NIH in its first round for scale-up.

6. How do we roll out a vaccine equitably?

When a COVID-19 vaccine is ready, who gets it first? The elderly? Essential workers? Persons of color? People who live in underserved communities? These are some of the questions being explored before a vaccine becomes available because even if more than one vaccine is approved, supply is expected to lag demand for the first months.

Delivering the vaccine will also need to take into account community context and the differential impact of COVID-19. The virus has hit some communities much harder than others, with racial and ethnic minorities at increased risk of getting sick and dying. To track and respond to this differential health impact, public health researcher Shivani Patel and her colleagues have developed the COVID-19 Health Equity Dashboard to show the interplay between social determinants and COVID-19 epidemiological metrics at the county level. The public-facing tool curates, disseminates, and ultimately synthesizes actionable information to guide localized response to the epidemic over time.

A national committee co-led by former CDC director and Rollins distinguished professor emeritus Dr. Bill Foege has advocated for a phased approach to vaccine allocation that is based on assessing individual risk factors. “The virus simply doesn’t understand race, color; it does understand vulnerabilities,” he says.

Want to learn more? Please visit:

Emory University

Woodruff Health Sciences Center

Emory Healthcare

Support Emory’s COVID-19 Response

Emory News Center