RIGHT TIME.

RIGHT PLACE.

RIGHT LEADER.

Gregory L. Fenves brings an extraordinary set of skills and experiences to lead Emory University through extraordinary times as its 21st president.

Last November, when the Emory Board of Trustees began its search for the university’s 21st president, no one could have anticipated what lay ahead. Within a few months, a global pandemic would claim countless lives, paralyze communities, tax health care systems and threaten economies. At the same time, protests challenging America’s legacy of racist violence would erupt across the US and eventually, the world.

Arguably, there has never been a more challenging time to be a leader in higher education.

But Fenves, who stepped into his new role as Emory’s president on August 1, arrived understanding full well the unusual scope of what awaited him. And he knows key questions will need to be answered.

What is the role of higher education in the face of a pandemic? How do we develop a blueprint for moving forward? Quite simply, how do universities go on in this new environment?

We stand in a profound, complicated moment of humankind’s history, to be sure. For Fenves, however, it is also a catalytic moment — one charged with possibilities for innovation and discovery, collaboration and engagement. He sees universities as critical players in finding the way forward: pivotal change agents poised for just this kind of transformative, impact-driven work.

“It’s an unprecedented time,” Fenves says. “But I would like to use it as a time of not just surviving, but thinking critically and creatively about what we do, collaborating and continuing the education of students and the research that is vital to society. We’re at a moment of opportunity, one where Emory can show leadership. I was drawn to Emory because of its tremendous academic programs and its tremendous desire to be even better.”

Then again, he has never been one to back away from a challenge. Those who’ve worked alongside him will tell you that solving problems may well be among his greatest strengths, and Fenves approaches the task with a resolute sense of purpose.

In fact, much of his thirty-six-year career in higher education — as a professor, researcher, and administrator — has been spent unraveling problems. Listening, collaborating, gathering information, evaluating possibilities, and creating decisive solutions constitute a typical day at the office.

As a child, Fenves would dismantle a tape recorder to understand how it fit together — a future structural engineer in the making. And as a top university administrator, he has continued that reverse-engineering practice, carefully untangling issues and immersing himself in their inner workings to better inform his decisions.

That, say his higher education colleagues, is who Fenves is: engaged, practical, strategic.

“When President Sterk announced her retirement last fall, our commitment was to identify a group of superior candidates and move aggressively to secure the best one for Emory. Our criteria were clear: superior academic credentials, deep experience as a leader, a proven team builder, an excellent communicator, unimpeachable integrity and someone who understands and appreciates the potential for Emory.”

“Greg’s record as a professor, dean, and president is outstanding. He is highly regarded across the academic community, and he has also drawn rave reviews from students, parents, community leaders and others. What we were told, and confirmed in our interviews, is that Greg is a person with exceptional vision, drive, and creativity. I also found him to be highly confident but refreshingly humble.”

—Robert C. Goddard III, Chair of Emory’s Board of Trustees and the Presidential Selection Committee

ENGINEERING SOLUTIONS TO HIGHER EDUCATION'S CHALLENGES

For the past five years, Fenves served as president of the University of Texas at Austin (UT), the state’s top-ranked public university, a position that built upon earlier roles as UT’s executive vice president and provost, and dean of the Cockrell School of Engineering.

As president of the University of Texas at Austin (UT), Greg Fenves played an instrumental role in the creation of the Dell Medical School and in supporting health care innovation.

As president of the University of Texas at Austin (UT), Greg Fenves played an instrumental role in the creation of the Dell Medical School and in supporting health care innovation.

From his first days leading the state’s flagship university, Fenves faced tough issues and difficult choices. Under his tenure, UT Austin successfully defended the university’s practice of using race and ethnicity in admission decisions before the US Supreme Court. It expanded financial assistance and support to low- and middle-income undergraduates and raised four-year graduation rates to record levels. It also opened the Dell Medical School — the first new, from-the-ground-up US medical school to open at a major research university in nearly fifty years.

With an eye on strengthening academic excellence, under Fenves’ guidance the university also expanded interdisciplinary research and launched a faculty investment initiative to support competitive salaries, retention and senior recruitments.

Fenves is also widely credited with helping steady relations with UT system regents and elected leaders, some of whom had pushed to see the university function more like a for-profit business. His success in steering the university through those rough waters is frequently ascribed to his leadership strengths, particularly his analytical skills and unwavering composure. In fact, UT colleagues insist he’s often at his best in the face of challenge.

“He’s quite good at crisis,” says Clay Johnston, dean of UT’s Dell Medical School and vice president for medical affairs. “He loves to solve problems, bringing people together to study things from all angles. He likes to see the data behind an issue, but is also really careful and thoughtful about the human aspect of things, such as how would a decision impact this person, this group, this viewpoint.”

Johnston adds: “Greg is a real person and lets you know it. He’s comfortable in his humanity.”

Fenves has always loved to keep up with cutting-edge technologies, such as augmented reality systems pioneered at UT.

Fenves has always loved to keep up with cutting-edge technologies, such as augmented reality systems pioneered at UT.

In the search for a new president, Emory was seeking someone with just that kind of balance — a leader who offered both a well of experience and an approachable, human touch in meeting the opportunities and future challenges of higher education.

“Our criteria were clear: superior academic credentials, deep experience as a leader, a proven team builder, an excellent communicator, unimpeachable integrity, and someone who understands and appreciates the potential for Emory,” says Robert C. Goddard III, chair of Emory’s Board of Trustees and the Presidential Selection Committee.

Beyond Fenves’ outstanding record as a professor, dean and president, “he is highly regarded across the academic community, and he has also drawn rave reviews from students, parents, community leaders, and others,” Goddard says. “What we were told, and confirmed in our interviews, is that Greg is a person with exceptional vision, drive, and creativity. I also found him to be highly confident but refreshingly humble.”

Fenves poses with his two daughters and granddaughter at a UT game.

Fenves poses with his two daughters and granddaughter at a UT game.

Perhaps most exciting, says Goddard, is the confidence and enthusiasm Fenves has for Emory’s future. “It’s his view that Emory has the necessary ingredients to accelerate its climb to national and international leadership. I couldn’t be more excited about the opportunity to work with him.”

“These are challenging times — COVID-19 has changed the way we live, work, play, and learn. Like the rest of the world, many leaders across the Emory campus have been grappling with the uncertainty and ever-changing presence of this pandemic and what it means for our faculty, staff, students and trainees, patients, and community. And I can say without a doubt, Greg Fenves is the right choice for Emory.”

“The magnitude and fluidity of these issues are tremendous, and yet Greg continues to approach each one methodically — learning quickly and adapting along the way. Even more important than his measured approach to problem-solving is what he has revealed to us about his character; he is respectful, open-minded, decisive, calm, and above all, principled. I look forward to the days when the challenges become a little less complex, but trust fully, that Emory is in good hands.”

—Jon Lewin, Executive Vice President for Health Affairs

COURAGE TO MAKE THE RIGHT DECISIONS

To better understand Fenves’ decisive approach to leadership, it helps to start with a nine-foot-tall, twelve-hundred-pound bronze statue.

Years before the current national debate over Confederate statues, and only two months into his UT presidency, Fenves made a bold move. Since the 1930s, a towering bronze sculpture of Jefferson Davis, former president of the Southern Confederacy, had stood on UT’s Main Mall, the symbolic heart of the campus — among a series of statues commissioned long ago by a Texas businessman and Confederate army major, who had himself fought at Shiloh and Chickamauga.

Over time, the Davis statue had attracted controversy and protest, and a few months before Fenves took office, UT’s student government passed a resolution calling for its removal. Following the June 2015 slayings of nine Black parishioners in Charleston’s Emanuel A.M.E. Church, those demands intensified.

Fenves led the effort to remove Confederate statues from prominent public areas on UT's campus, including this statue of Jefferson Davis in 2015.

Fenves led the effort to remove Confederate statues from prominent public areas on UT's campus, including this statue of Jefferson Davis in 2015.

In response, Fenves quickly organized a task force to evaluate the “contextual appropriateness” of the statue, as well as others. “Basically, he used the expertise on campus to gain consensus among multilayered constituencies, and it worked,” recalls Cherise Smith, chair of the African and African Diaspora Studies Department at UT. “It was a decisive move, streamlined and deliberate. I was very, very impressed.”

Despite a legal challenge, Fenves decided the Davis statue would be forklifted from its limestone pedestal and relocated to UT’s Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, destined to become part of an educational exhibit.

“While every historical figure leaves a mixed legacy, I believe Jefferson Davis is in a separate category, and that it is not in the university’s best interest to continue commemorating him on our Main Mall,” Fenves explained in a letter to the UT community.

Two years later, he did it again. Following violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, over the removal of a Confederate statue, Fenves revisited the 2015 task force findings.

While preparing for church, Leonard Moore, vice president of UT’s Division of Diversity and Community Engagement, recalls his phone ringing early one Sunday morning. At midnight, Fenves calmly told him, four more statues would be coming down — including two Confederate generals, Robert E. Lee and Albert Sidney Johnston, and Confederate cabinet member John Reagan — slated to join the Davis statue as part of the Briscoe Center collection. Moore was impressed, both with Fenves’ gutsy decision and the courtesy of an advance alert.

Days before students returned for classes — and with little fuss or fanfare — the statues were removed. In a community letter, Fenves said that after the violence in Charlottesville, it had become clear to him that Confederate monuments had become symbols of modern white supremacy and neo-Nazism. “We do not choose our history, but we choose what we honor and celebrate on our campus,” he wrote.

Earlier this year, Emory history professor Joe Crespino joined faculty colleagues on the presidential search committee for a luncheon with Fenves. To a person, they reported it was hearing his account of those decisions that convinced them: Fenves was the one. They believed he was the next person who should lead Emory.

Beyond Fenves’ broad knowledge about higher education — a wide range of experiences as an administrator, researcher, teacher, and scholar — “to hear him talk through the challenges he faced at the University of Texas, particularly the decision to remove the Confederate statues — as a historian, I found it enormously impressive,” says Crespino, Jimmy Carter Professor of History and chair of Emory’s Department of History.

Fenves has dived right in to his duties as Emory president, including hosting a virtual Q&A session on his first official day on the job.

Fenves has dived right in to his duties as Emory president, including hosting a virtual Q&A session on his first official day on the job.

“It showed he has an essential quality of leadership, a clarity of vision to know when to take a stand and where to draw the line,” he adds. “I think that was when I realized we had an incredible opportunity here.”

In her thirty-one years at Emory, Nancy Newman has served on more search committees than she can count. This one, she says, was different. “He’s a fabulous strategist who doesn’t shy away from the hard things,” Newman says about Fenves. “Through his experience, he’s shown us time and again, these are situations where he shines. The more we plumbed his depths, the more greatness we found.”

She left that day “with such excitement, absolutely energized.” Newman, LeoDelle Jolley Chair of Ophthalmology at the Emory School of Medicine, recalls thinking, “This is a guy who makes me want to work at Emory another thirty years.”

With a record of promoting social, economic, and racial equity for UT students, Fenves is already engaging with some of those issues at Emory. When a coalition of Emory Black student organizations reached out to administrators over the summer with concerns and demands, he helped lead efforts to listen, talk with them, and respond — well before he had actually stepped into his new role.

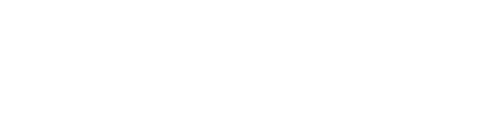

President Fenves recently toured Emory University Hospital, stopping frequently to thank frontline health care workers along the way.

President Fenves recently toured Emory University Hospital, stopping frequently to thank frontline health care workers along the way.

“When a president who doesn’t even officially start the job until August 1 has given students an audience, that’s a very good sign of things to come,” says Carol Henderson, vice provost for diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer. “He’s a motivator and a collaborator, already listening and connecting with community members.”

Across the nation, “we are at an enormous moment of change and reflection — so many institutions are being asked to address questions and think of history and racial legacies in ways they haven’t in many decades,” Crespino adds. “To have someone with Greg Fenves’ experience and also his own personal history, his own personal story, at Emory in this moment is so powerful.”

“When it comes to navigating the challenges of leading a university, President Fenves has a long history of reacting promptly, thoughtfully and strategically — working collaboratively with his constituencies and investing in decisions that support students, faculty and researchers. He is a distinguished scholar and inspired leader whose vision reflects his own personal integrity and exceptional character. I am confident that he will lead Emory forward with boldness and ambition into a bright future.”

—Jan Love, Interim Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, Mary Lee Hardin Willard Dean of Candler School of Theology

GROWING UP ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES

Fenves grew up in the American heartland with a childhood spent around universities — one of four children born to Steven J. Fenves, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Norma Fenves, a clinical social worker.

For Fenves and his siblings, the university campus became as familiar as their own backyard. Visits to his father’s office meant running across the street to explore the student union, eat in the cafeteria, visit the bowling alley, or catch a campus movie. Summer months were spent at camps hosted at the university.

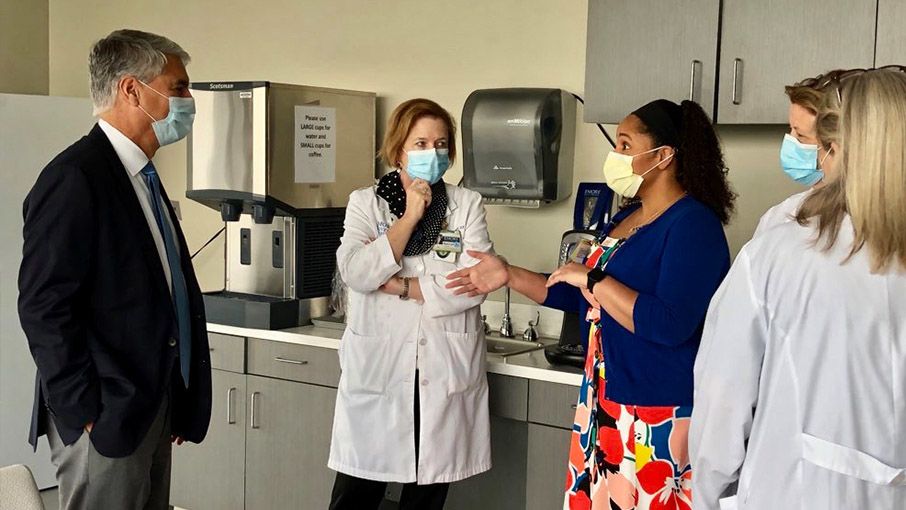

Fenves received master and doctoral degrees in civil engineering from the University of California, Berkeley in 1980 and 1984.

Fenves received master and doctoral degrees in civil engineering from the University of California, Berkeley in 1980 and 1984.

By high school, the Fenves family had moved just outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where his father joined Carnegie Mellon University as a widely respected professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. In 1976, Steven Fenves was elected to the National Academy of Engineering for his pioneering work in applying computers and problem-oriented programming to civil engineering.

Fenves will tell you that he was like many kids — interested in tinkering with erector sets, building things, and taking them apart. Even now, he enjoys watching his three-year-old granddaughter construct imaginary cities for her toy animals. By the time he was in high school, he traded toys for science projects and a growing interest in computers — a burgeoning new field at the time.

As a young child and teenager, Fenves spent a great deal of time at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and then at Carnegie Mellon University, where his father worked as a professor.

As a young child and teenager, Fenves spent a great deal of time at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and then at Carnegie Mellon University, where his father worked as a professor.

By the early 1970s, Fenves was already teaching himself programming, envisioning a career in computer science. He chuckles to recall the excitement of picking up Popular Electronics magazine to see an advertisement for the Altair 8800 — a kit to construct what was essentially the world’s first home microcomputer — and the disappointment of learning that his mother didn’t share his enthusiasm for the seven-hundred-dollar investment.

Greg Fenves began his undergraduate studies at Cornell University fully expecting to major in the emerging field of computer science. However, disappointed in his first computer programming class, he quickly switched to structural engineering. Today, he often shares that life lesson with students, urging them to approach college classes with an open mind: “One course or one professor shouldn’t determine your career,” Fenves cautions.

Ultimately, Fenves would pursue scholarship that blended both engineering and computer science. After earning his bachelor’s degree in engineering at Cornell with distinction, he headed to the University of California, Berkeley, to continue graduate studies, arriving about eight years after the deadly San Fernando Earthquake, a 6.5 temblor that left a wake of death and destruction in Southern California.

But the devastating event had also fed a fast-growing field of study: earthquake engineering. And on the West Coast, UC Berkeley sat at its epicenter. From analysis and modeling to studying the spectrum of earthquake motions, computers would play an essential role in that scholarship.

After earning a master of science degree, Fenves stayed at UC Berkeley for doctoral studies, where he found satisfaction in both research and teaching. In the classroom, “there was a sense of excitement, new ideas, new problems to be confronted, and new ways to solve those problems,” he says.

After launching his teaching career at UT Austin in 1984, Fenves returned to UC Berkeley in 1988, where he would eventually chair the university’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, among the nation’s top programs. Three decades later, in 2014, he was elected to the National Academy of Engineering for his own groundbreaking research in earthquake engineering, as well as his academic leadership.

Universities, he found, were unique institutions, “where very smart people have the freedom to think deeply as individuals and as an intellectual community about humanity, society, and addressing difficult problems.”

As a university president, Fenves is used to being front and center at campus events, and relishes the opportunities to listen and learn from students, parents, and alumni.

As a university president, Fenves is used to being front and center at campus events, and relishes the opportunities to listen and learn from students, parents, and alumni.

“And you are always dealing with young people and education in an environment that changes all the time,” he reflects. “In fact, some of my closest relationships have been with my former students, who still keep in touch.”

“President Fenves is a great fit for Emory, especially in these unparalleled times. He brings an outstanding record of administrative and academic excellence that includes an unwavering commitment to unlocking the full potential of students.”

“At his previous institution, he spearheaded innovative programs and expanded education resources for undergraduate and graduate students. The result was enhanced student success, improved retention, and record increases in four-year graduation rates. Along the way, Dr. Fenves has demonstrated an exceptional ability to engage students, from enjoying fun moments like carpool karaoke to addressing challenging issues like race and social justice.”

—Enku Gelaye, Vice President and Dean of Campus Life

DRAWING UPON THE POWER OF HIS FAMILY’S STORY

As a university president, Fenves is experienced in presenting a public face for the university — his focus understandably on the institution. He’s less accustomed to putting the spotlight on himself.

But a few years ago, Fenves surprised many colleagues by opening up about his own family story. While receiving the Guardian of the Human Spirit Award at the Holocaust Museum Houston in 2017, Fenves spoke “more personally than I am used to” as he shared a deeply American story, one “that helps define who I am, and a story about our nation — my father’s story.”

Fenves (right) poses with his father, Steven, and mother, Norma, at the Holocaust Museum Houston's Guardian of the Human Spirit Award ceremony in 2017, where he told his family's story of survival.

Fenves (right) poses with his father, Steven, and mother, Norma, at the Holocaust Museum Houston's Guardian of the Human Spirit Award ceremony in 2017, where he told his family's story of survival.

Fenves was eight years old when he learned that his father was a Holocaust survivor. He recalled slipping into his parents’ bedroom while his father napped to peek at the telltale numbers tattooed upon his arm. And he described his father’s harrowing journey, from growing up in a prosperous, educated Jewish-Hungarian family in Yugoslavia to seeing their home, business, and possessions confiscated under Nazi occupation.

In 1944, thirteen-year-old Steven Fenves and his family were placed in cattle cars destined for Auschwitz. Steven’s grandmother was quickly taken to the gas chamber; his mother would later die in a separate compound. He and his sister were assigned to youth blocks, where he worked in a slave labor camp. At the war’s end, young Fenves was among only a handful of relatives to emerge from the camps — including his sister and his father, who was near death. Before his passing, the elder Fenves wrote to a friend in New York, with the hope that his children might move to America.

In 1950, Steven Fenves and his sister arrived in Chicago. He was drafted into the US Army and, in an ironic twist of fate, was eventually deployed to join the country’s occupation forces in Germany.

Speaking at the award ceremony, Greg Fenves acknowledged that he had never before discussed his father’s story outside the family. But by sharing it, by understanding history, “we understand our own story — as individuals, as a society, and as a nation,” he reflected. “That is the power of a story.”

Watch an excerpt from President Fenves’ Guardian of the Human Spirit Award acceptance remarks at the Holocaust Museum Houston in 2017.

At Emory, Fenves has arrived prepared to help tell another important story: the next chapter in the life of the university. It will no doubt be a tale that features remarkable challenges and unexpected plot twists, struggles, and surprises.

But it will also be one of incalculable contributions, with possibilities for discovery and learning and unimagined advances in the service of humanity — poised to unfold at this important, catalytic moment.

That story now rests in Greg Fenves’ capable hands. And he’s ready to turn the page.

By Kimber Williams. Photography by Kay Hinton, the Fenves family, and the Holocaust Museum Houston. Design by Elizabeth Hautau Karp.

THE PRESIDENT'S PARTNER

With a background steeped in family, creativity, and culture, Carmel Martinez Fenves brings her own brand of warmth and engagement to work on campus.

While sharpening his amateur sailing skills with friends on the San Francisco Bay decades ago, Emory President Greg Fenves charted an unexpected, life-altering course: He met the love of his life and his future wife, Carmel Martinez.

Greg and Carmel share a special, complementary partnership both on and off campus.

Greg and Carmel share a special, complementary partnership both on and off campus.

A textile artist and first-generation college student, Martinez had grown up in the Bay Area within a large, extended family that met for boisterous weekly gatherings filled with food and laughter and music. Her parents’ roots extended back into Mexico, and her mother’s plan was always to see her children attend college. After two years at Santa Rosa Junior College, Martinez transferred to UC Davis, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in textile arts.

On the day she met Fenves, she had been invited by mutual friends to join them for a sailing cruise. When the group later migrated to a bar in Tiburon, she found herself in conversation with the sailing vessel’s dark-haired young deckhand, whom she learned was an engineering student at University of California, Berkeley.

A family portrait of Greg and Carmel with their two daughters, granddaughter, and son-in-law.

A family portrait of Greg and Carmel with their two daughters, granddaughter, and son-in-law.

In time, she would come to admire him for his intelligence, composure and ability to focus on what really matters. “I like the way he analyzes things,” she explains. “He’s quick, very logical; he sees past a lot of stuff to grasp what is immediately important.”

Together, they’ve been married thirty-six years, and raised two daughters, both now adults — the rhythm of their family life always tied to an academic calendar. Fenves considers his wife an important partner in his presidential role. Friends describe them as two sides of the same coin. If he is introspective, she is an unrepentant extrovert — quick to laugh and willing to talk with everyone.

“No matter who you are, she greets you with an authentic warmth and interest — a model of accessibility and welcome without the slightest pretense,” says Paul Goldbart, dean of the College of Natural Sciences at UT Austin. “I know that she meets hundreds of people, but it’s almost as if you’re bumping into a cousin you haven’t seen in a while.”

Greg and Carmel dance at a University of Texas event in 2010.

Greg and Carmel dance at a University of Texas event in 2010.

At UT Austin, Carmel Fenves played an active role in the university’s initiative to support first-generation students and she looks forward to exploring those interests at Emory. “I love to hear First-Gen stories — every one is slightly different,” she says. “I also like to look beyond their university experience. What happens to you and your family when that First-Gen student is successful and their life changes? How does that fit back into your family life? Each family has a different response. … I’m always interested in what happens next.”

Though to date, neither Fenves has spent a great deal of time in Atlanta, they’ve been reading up on the region, particularly its role in the US civil rights movement. Carmel Fenves says she will especially enjoy learning more about how the history of the university fits within the history of Atlanta.

Following their many years in Texas, Greg and Carmel Fenves are excited to take on new adventures at Emory and learn more about Atlanta.

Following their many years in Texas, Greg and Carmel Fenves are excited to take on new adventures at Emory and learn more about Atlanta.

And though it is somewhat bittersweet to arrive on campus amid a pandemic — she knows it will be a while before she experiences the Emory campus as it existed this time last year —there is still much to look forward to.

“I’m very excited to be Greg’s partner in this,” she says. “We’re so grateful for the opportunity.”

By Kimber Williams. Photos courtesy of the Fenves family. Story design by Elizabeth Hautau Karp.

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Magazine, Emory News Center and Emory University.