ROLLINS RESPONDS

Faculty, staff, and students rise to the challenge of addressing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Never is the mission of public health—to promote, protect, and advance health in all communities across the globe—more critical than in a pandemic. This is our wheelhouse.

This is what we do.

—Dean James W. Curran

As the world reels from a lethal new virus with no current vaccine or treatment, all eyes turn to public health for answers and solutions. Rollins is providing them.

From advising state and local officials to appearing in the media to answer questions and dispel myths, and from devising models to predict hotspots to rolling up their sleeves and calling people who might be infected, Rollins faculty, staff, and students are focusing their skills, expertise, and passion on the outbreak response. One professor is advising correctional facilities on how best to deal with infected inmates. Another has turned the pandemic into a real-time case study for his students. And another is using data from the first quarantined cruise ship to study how the virus spreads in a dense environment.

That work will continue long after hospitals have discharged their last COVID-19 patients as public health professionals turn their attention to gaps highlighted by the pandemic. “We need to understand the underlying causes of the large disparities in mortality rates,” says Dean James Curran. “We must foster more transparent communication between countries and agencies. We need to evaluate our surveillance methods.

“This pandemic will be a defining moment in our careers,” Curran continues. “And I could not be more pleased with how the Rollins community is responding.”

Partnering with county and state

The Georgia Department of Public Health (GDPH) and the Fulton County Board of Health (FCBOH) are partnering with Rollins on their COVID-19 response. As chair of the board for the GDPH, Dean Curran has been consulting with Kathleen Toomey, the department’s commissioner, since the earliest days of the pandemic. More recently, Dr. Allison Chamberlain, acting director of the Emory Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research, has begun directing a school-wide partnership with the GDPH.

One group of Rollins faculty and students, led by Dr. Hannah Cooper, Rollins Distinguished Professor of Substance Use Disorders, and Dr. Carmen Marsit, associate dean of research, is helping GDPH understand the racial inequalities in the COVID-19 burden and mortality and identify hotspots through geospatial analysis. They are also conducting syndromic surveillance to detect places that are vulnerable to an outbreak before there are confirmed diagnoses, analyzing transmission dynamics, and modeling the impact of different interventions, among other things.

Julie Clennon works—remotely—with the Georgia Department of Public Health to interpret spatial analysis results.

Julie Clennon works—remotely—with the Georgia Department of Public Health to interpret spatial analysis results.

Another Rollins group—Dr. Julie Clennon, instructor in biostatistics and bioinformatics; Uriel Kitron, professor and chair of the environmental sciences department at Emory and professor of environmental health and epidemiology at Rollins; and Ian Hennessee, doctoral student in environmental health—is working with GDPH colleagues to look at the spread dynamics in space and time throughout the state, and to identify emerging clusters of concern.

“How do you go from getting spatial statistics to applying them to make decisions, such as where to best put your resources?” says Clennon. “We are all experienced in interpreting the data and that’s where we can help.”

In addition to her work with the GDPH, Chamberlain has worked as an epidemiology consultant with the FCBOH since 2017. She has supported high-profile response activities, including activation of the county’s emergency operations center for the 2019 Super Bowl and supporting its response to the deadly Legionnaires’ Disease outbreak associated with a downtown hotel in that same year.

Because of her consultancy, she was working with the health department even before COVID-19 was identified. More recently she has joined forces with Drs. Neel Gandhi and Sarita Shah, associate professors of epidemiology, to lead a group of Emory staff and doctoral students to assist with outbreak response.

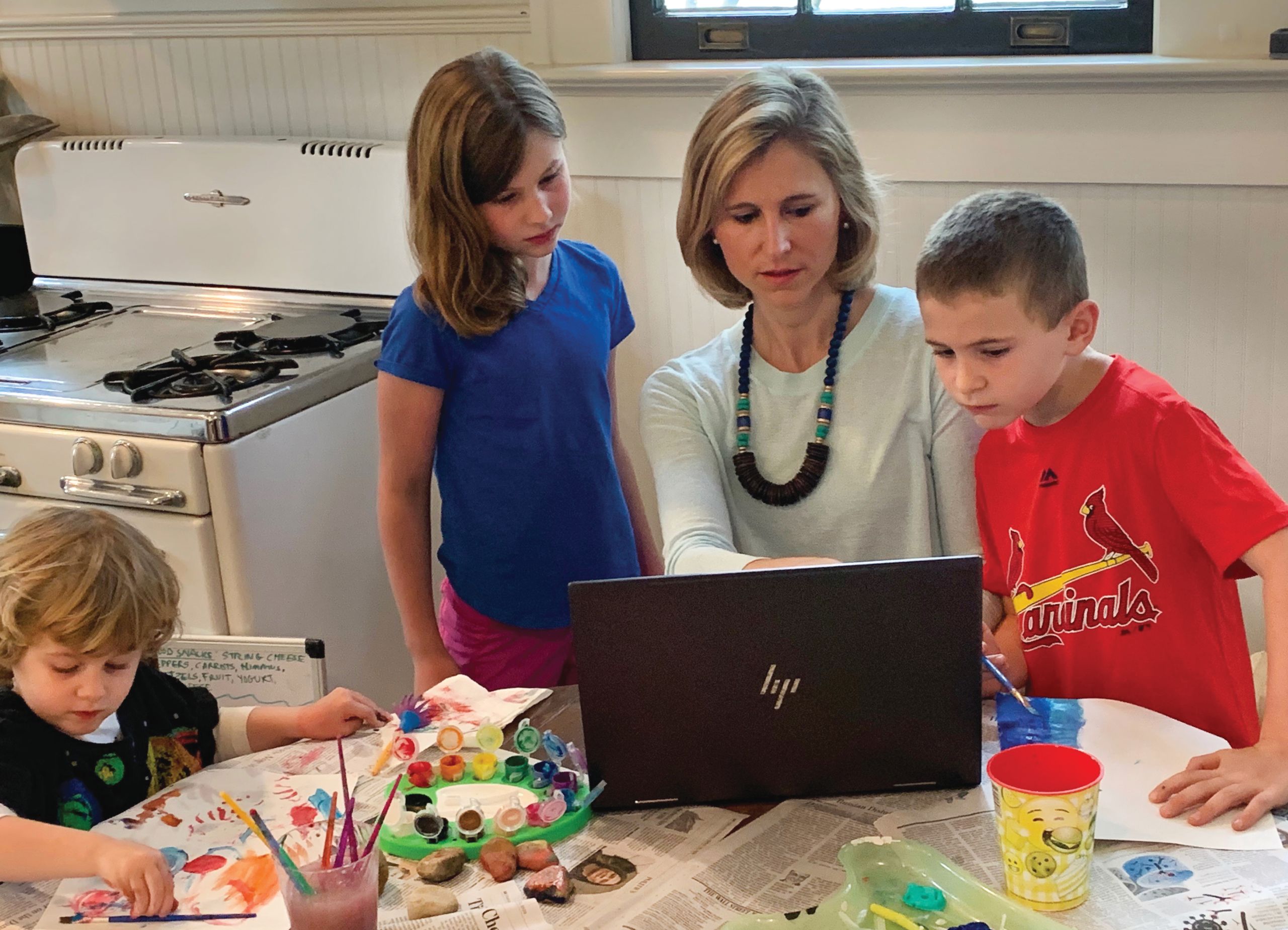

Allison Chamberlain directs the school’s collaboration with the Georgia Department of Public Health from her home.

Allison Chamberlain directs the school’s collaboration with the Georgia Department of Public Health from her home.

Chamberlain heads a surge capacity/case investigations team that calls people diagnosed with COVID-19 to glean extra data, such as date of symptom onset, their demographics, a more complete medical history, and course of the illness. Gandhi and Shah coordinate the analytics/data visualization team, helping with geospatial mapping of cases around the county to gain an understanding of changing rates of infection and hotspots.

“These are scary, uncertain times, but I am thrilled to see this level of collaborative engagement right now between Rollins and a local health department,” says Chamberlain.

Sharing expertise

Never is concise, evidence-based communication more important than in a time of crisis. Radio, TV, and print journalists have called on the expertise of Rollins scientists again and again to help understand and explain the fluid complexities of the novel COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Carlos del Rio, executive associate dean for Emory at Grady and professor of infectious diseases, epidemiology, and global health, has appeared in national media on a seemingly daily basis. Drs. Matthew Freeman and Karen Levy, associate professors of environmental health, and Dr. Ben Lopman, professor of epidemiology, have been widely interviewed in the local and national media about the epidemiology of the outbreak. Levy helped coalesce a group of infectious disease scientists and clinicians in an open letter covered in Science magazine calling for quick and comprehensive action from governments.

Lopman and Chamberlain participated in virtual town halls with state representatives Hank Johnson (4th District) and Lucy McBath (6th District), fielding questions from more than 7,000 concerned constituents who called in to ask about vaccine development, effectiveness of wearing masks, how long the virus can live on surfaces, and much more.

Carlos del Rio is widely quoted in the media. Here he gives an interview on WABE before shelter-in-place orders went into effect. Photo credit: LaShawn Hudson, WABE

Carlos del Rio is widely quoted in the media. Here he gives an interview on WABE before shelter-in-place orders went into effect. Photo credit: LaShawn Hudson, WABE

Serving different communities

Dr. Anne Spaulding, associate professor of epidemiology and director of the Center for the Health of Incarcerated Persons at Rollins, has long studied the health of a particularly vulnerable population— residents of prisons and jails. Given that half of people who are incarcerated have a chronic medical condition and many are older thanks to spillover from the “three-strikes” law, this population is at high risk for COVID-19.

Spaulding has been spending the bulk of her time since the pandemic hit advising correctional leaders and staff across the country and the world on how to protect themselves and their charges. A lot of facilities built in the 1990s opened when there was still a lot of tuberculosis circulating within the prison population, so those facilities tend to have many negative-pressure rooms in which sick, infectious prisoners can be isolated. How should isolation be handled in other facilities? Is reducing prison populations by releasing vulnerable prisoners a good idea?

Anne Spaulding advises leaders of correctional facilities on dealing with COVID-19 in their populations.

Anne Spaulding advises leaders of correctional facilities on dealing with COVID-19 in their populations.

The Interfaith Health Program, led by Dr. John Blevins, associate professor of global health, and Mimi Kiser, assistant professor of global health, has developed a platform of resources for faith communities and religious leaders to support a scientifically sound and pastorally sensitive response to the COVID-19 outbreak. The site offers resources on everything from infection control to congregational care and from community support to specialized ministries, such as homeless ministries, food pantries, and eldercare.

Blevins and Kiser are working with the World Health Organization and other global partners to adapt guidance for infection control and prevention developed in high-resource countries for use in low-resource countries. “The current guidance assumes socioeconomic contexts that simply don’t apply in much of the world,” says Blevins. “There is a huge need to adapt it so it is practical and effective for communities and households in lower- and middle-income countries.”

John Blevins and Mimi Kiser lead the Interfaith Health Program, which has developed a platform of resources for faith communities.

John Blevins and Mimi Kiser lead the Interfaith Health Program, which has developed a platform of resources for faith communities.

Refocusing research

Where is COVID-19 likely to spread next? When a vaccine becomes available, what is the most efficient way to distribute it? When will disease incidence peak in different areas?

For answers to questions like these, government and public health officials turn to infectious disease modeling experts. Ben Lopman and Dr. Sam Jenness, assistant professor of epidemiology, are just such experts, and they have been retooling previous research to address COVID-19.

Lopman was already planning a study to evaluate the value of people working from home rather than in offices during a flu pandemic to see if it was an effective way to slow the spread of disease. He was gearing up to start the study in the fall when COVID-19 hit. “We are dealing with a pandemic that has driven people to teleworking in unprecedented numbers,” he says. “So we are moving quickly to conduct this study with a number of companies in the Atlanta area to look at how people’s patterns of social mixing have changed and how that has impacted the spread of COVID-19.”

Ben Lopman is retooling modeling work he has done on other infectious diseases to apply to COVID-19.

Ben Lopman is retooling modeling work he has done on other infectious diseases to apply to COVID-19.

Lopman and his team have already done a lot of work modeling norovirus and rotavirus vaccines, simulating the impact of vaccination at different coverage levels on child deaths and illness. “We are adapting those models to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19,” he says. “When a vaccine becomes available, we want to be ready to advise on the best way to distribute it to optimize the public health impact.”

Jenness and his team have developed network models to represent infectious disease transmission in dense environments, using data from the Diamond Princess cruise ship, the first ship quarantined for COVID-19. His research seeks to evaluate the performance and timing of different behavioral (social distancing, isolating) and biologic (wearing masks, better hand hygiene) interventions in curbing transmission in dense environments. His findings would be applicable not only to cruise ships, but also to college dorms, nursing homes, and other places where people live in close quarters.

Earlier in his career, Jenness created a modeling tool, EpiModel, that is open source and freely available to researchers who want to model virus transmission. He is updating it to better work with SARS-CoV-2, and scientists have begun using it to model coronavirus transmission.

Students respond

When the pandemic spread to Georgia, members of the Student Outbreak and Response Team (SORT) were ready to help. Founded after 9/11, SORT partners with the CDC and state and local health departments to give Rollins students opportunities for hands-on experience responding to public health emergencies. Over the years, SORT members have worked with these partners on outbreaks of Ebola, SARS, and Zika.

SORT members first got involved with the GDPH, where SORT co-president Katelin Reishus 21MPH has been working on a viral respiratory pathogens team since October. In March, Reishus was asked to coordinate SORT volunteers to help with the outbreak response. Reishus and her colleagues were involved in active monitoring of travelers coming from China, Iran, and other high-incidence countries and contact tracing when COVID-19 cases were confirmed. As cases mounted and contact tracing became unsustainable, students switched to helping coordinate testing requests.

By mid-April, SORT students were volunteering their time and talents across the city. At the CDC, SORT students are fielding calls from quarantine stations. At the FCBOH, students are helping in the emergency operations center and bolstering the roster of the Medical Reserve Corps by reaching out to people with a background in public health or medicine.

They are lending their epidemiology skills to Emory University Hospital to help forecast personal protection equipment needs. SORT copresidents Reishus and Paige Harton 21MPH were tapped by Rollins to connect with leaders of all the other Rollins student organizations to make sure that the student perspective was included in the quickly developed plan for leaving campus for online learning.

Katelin Reishus (left) and Paige Harton lead the SORT COVID-19 response.

Katelin Reishus (left) and Paige Harton lead the SORT COVID-19 response.

“This is exactly the type of thing SORT was developed to do,” says Allison Chamberlain, the organization’s academic adviser. “This is their Super Bowl. This is all of our Super Bowl.”

The pandemic spurred the creation of a new student initiative, the COVID-19 CROWN Student Task Force. Bria Jarrell 21MPH wanted to gather student volunteers to help with the university’s COVID-19 response, so she posted on her class’s FaceBook group page to see if anyone was interested. They were.

The 40 slots were filled within a few days—participation in the initiative was capped to keep things manageable—and 25 students have signed up to be on the waiting list in case a spot opens.

The CROWN in the group’s name stands for each of the four volunteer teams, which include: Community Outreach, Research Monitoring, Outreach and Well-Being, and Needs Assessment.

The Community Outreach team recruited volunteers to help track COVID-19 in jails and to help the GDPH with contact tracing. In addition, team members are working with a local assisted-living facility, pairing students with residents to talk on the phone on a regular basis. The Research Monitoring team is the “lit review crew.” They monitor the literature and updates on the most current COVID-19 findings and translate them into easily understandable graphics and flyers.

The Outreach and Well-Being team partnered with Emory Campus Life to develop a “Distancing with Dooley” health communication campaign and with Emory’s counseling psychological services to host virtual peer- support groups for Rollins students. The Needs Assessment team developed a survey to assess student needs during this time, which they will share with the school’s administration.

“This group is 100 percent student-driven,” says Joanne Williams, assistant director for student engagement, who helped Jarrell in the early stages. “Students conceived it. They lead it. They make it work. It’s an incredible testament to the commitment and compassion of the students at Rollins.”

Story by Martha McKenzie

Designed by Linda Dobson

Want to know more? Please visit

Rollins Emory Public Health Magazine

Emory News Center

Emory University