OPENING DOORS

(and more)

The Storied Career

of Gary Hauk

If one were to accept his modest view, in the course of a 34-year career, Gary Hauk 91PhD has merely been opening doors — in his words, “smoothing the way and shepherding good ideas” through Emory.

To the rest of us, he has been a key figure in many major chapters in Emory’s evolution. Working closely with five presidents, his positions have included assistant secretary of the university, secretary of the university, vice president, deputy to the president, senior adviser to the president, and university historian. He retires on Jan. 1, 2020.

"Gary's presence and steady leadership across the university have had a lasting impact. His attention to Emory's history has shaped who we are as an institution and as an academic community over time."

—Emory President Claire E. Sterk

The graduate student shops around

Hauk, who attended Emory as a graduate student, came here as the result of a last-minute change of plans.

Having felt called to ministry but later drawn to academic career options, Hauk believed that the logical step after earning his MDiv at the Methodist Theological School in Ohio would be to pursue a doctorate as part of another school’s well-respected religion-and-literature program.

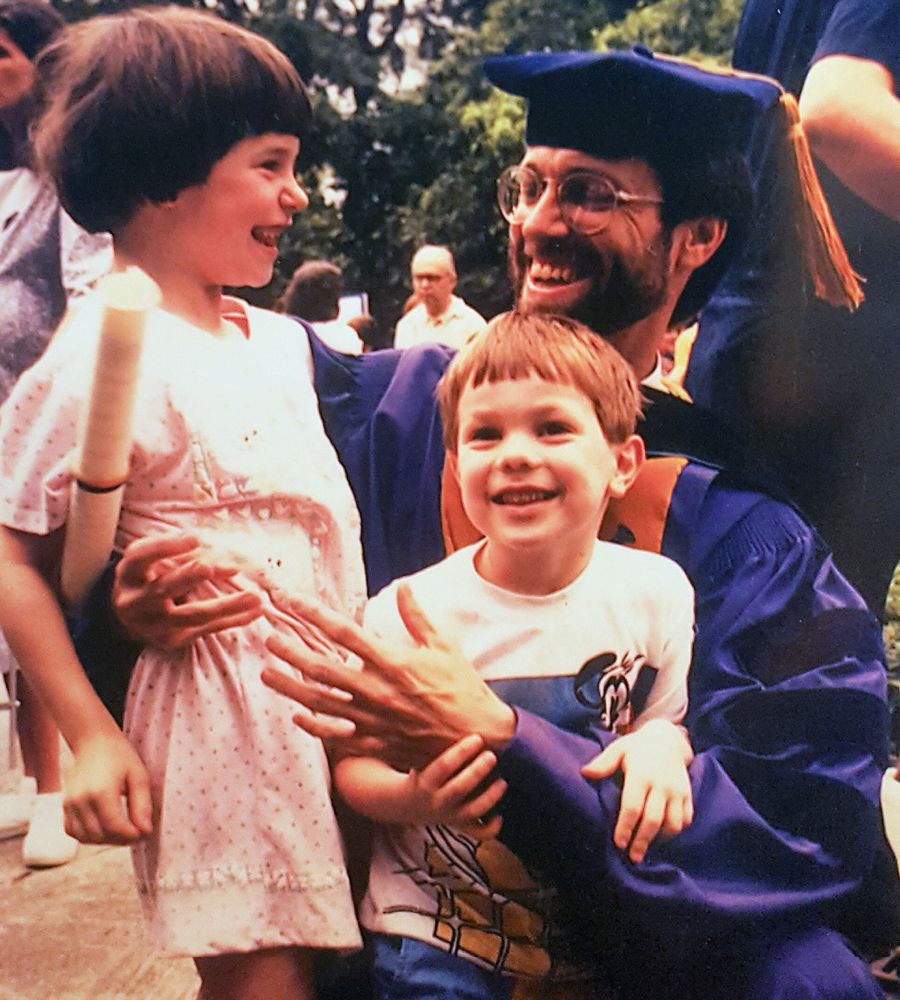

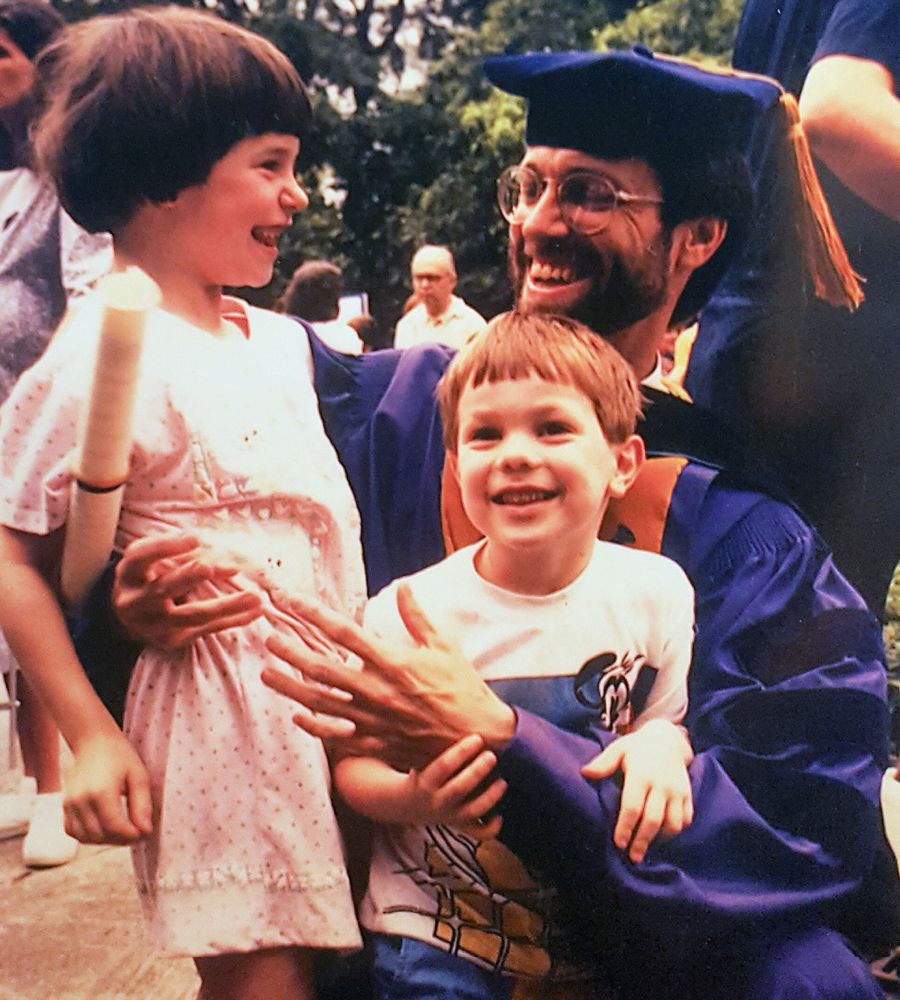

On the day he earned his Emory PhD in 1991, Hauk with his daughter Alexis and son Thomas,

But then he became aware of another option. “Emory, which I had never heard of, had started this new program in ethics and society,” says Hauk. In 1983, with President James T. Laney at the helm, the university was making good on the national competitiveness that the 1979 Woodruff Gift had made possible. One of Hauk’s professors knew several Candler School of Theology faculty members as well as Laney, who had risen to the presidency from the Candler deanship.

Finding the other program “very traditional” when he visited, Hauk came away from his Emory visit with everything but a ticker-tape parade in his honor. Numerous faculty meetings, including a half hour with Laney, were arranged. “I was struck by the dynamism, energy, and openness of this place,” notes Hauk.

Taking advantage of the unique opportunity to be taught by Laney — in a course titled Character and Moral Judgment — Hauk was turned on to Iris Murdoch after reading a collection of her essays as part of the coursework. Choosing her as the subject of his dissertation, he remains a lifelong admirer of Murdoch, saying, “Her book of essays turned me on to the complexities of human life and the ways in which ethical decision-making is other than we think. Often, our moral choices are made before we realize that we have made them.”

Earning a second doctorate in ‘Emory Studies’

As the Emory tour guide par excellence, Hauk can find his way to any nook or cranny on campus; he began this adventuresome spirit as a student, working as a reference librarian at Pitts Theology Library; a work-study student in Communications, writing press releases; and a production manager for Creative Services.

While still writing his dissertation in 1987, Hauk was asked to undertake what he describes as a “mega annual report — a retrospective of Laney’s first decade as president.” Titled “Emory at 150: A Report on the State of the University,” the project poised Hauk for deepening responsibility at Emory. “It was also,” he says, “me dipping my toe into the history of the institution.”

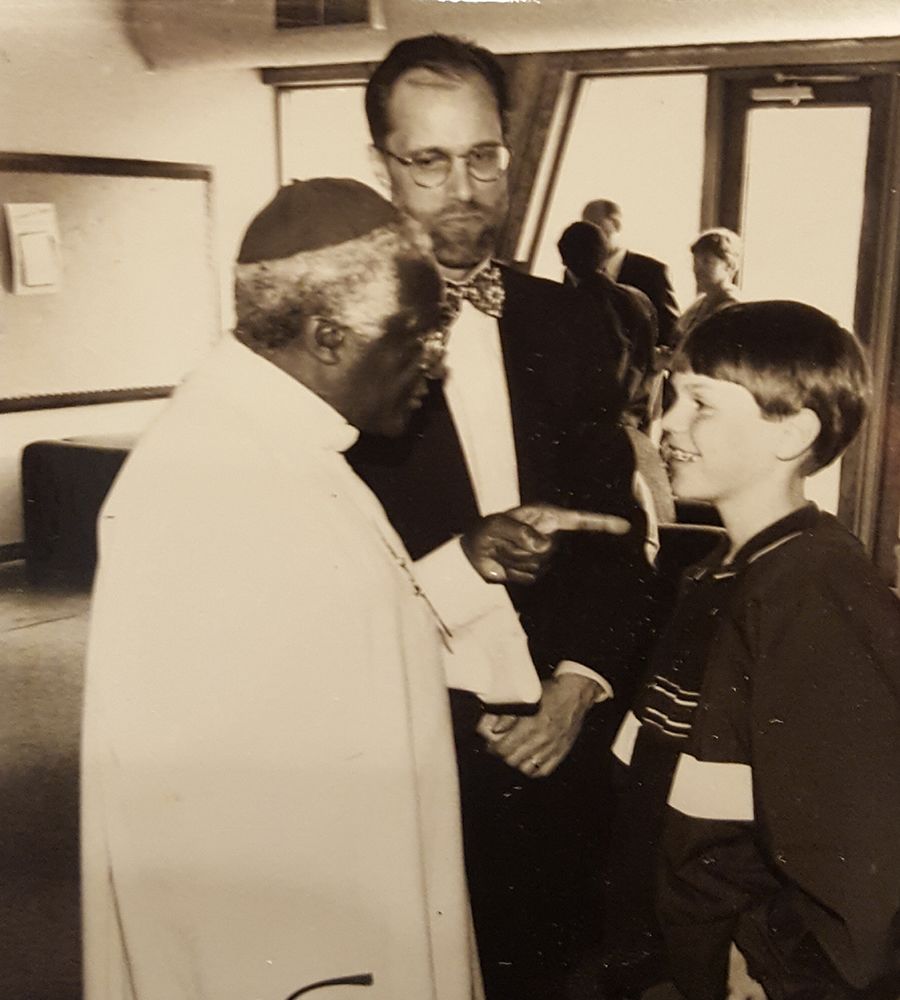

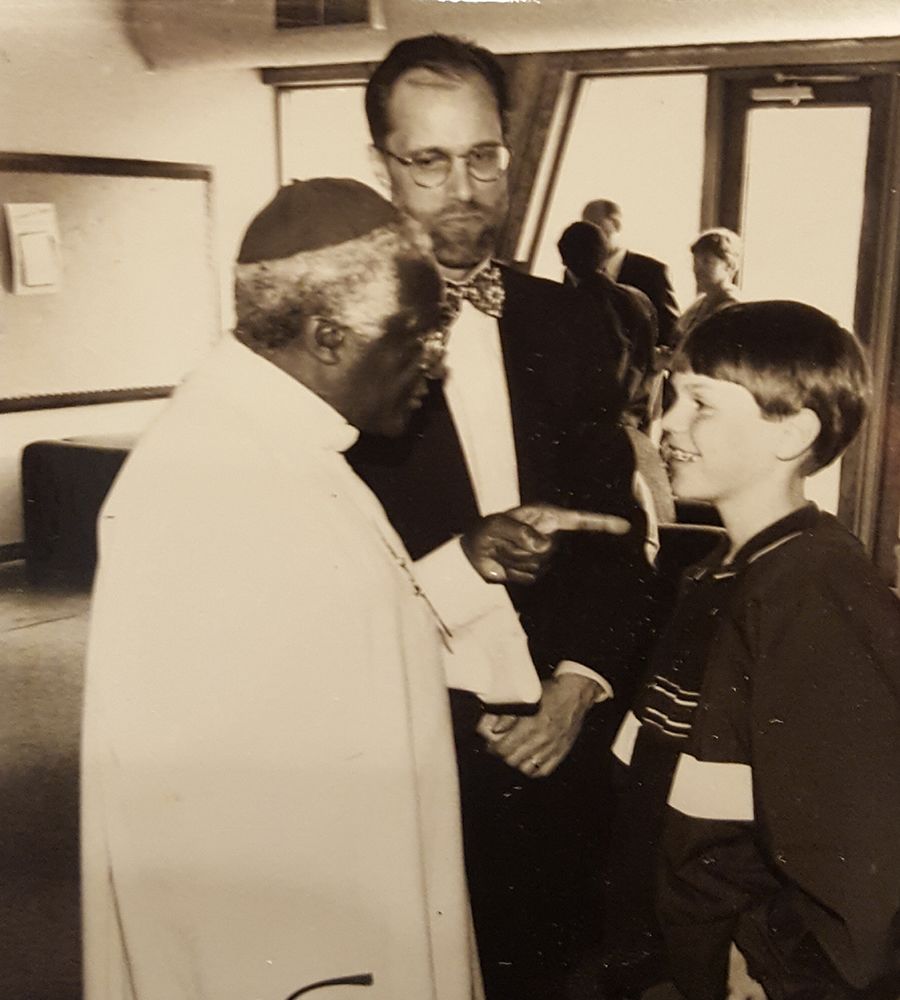

Hauk with Desmond Tutu during the archbishop's tenure as Visiting Woodruff Professor in 1998. Hauk's son Thomas is clearly receiving a strong recommendation from the archbishop.

One legacy of his time here is that Hauk has come to know major figures on the world stage, the first of which was Desmond Tutu — archbishop emeritus of Cape Town, South Africa — who spoke at Emory’s 1988 commencement.

Hauk was then interviewing for the position of assistant university secretary. Tom Bertrand, the university secretary, crafted a candidate exercise that required responding to an actual letter from an alumnus protesting Emory’s decision to invite Tutu.

Here, Hauk was called upon to do what would be required of him innumerable times during his tenure — to defuse tensions and respond thoughtfully to concerns about Emory’s positions or actions. In his response, Hauk wrote:

“The blood-letting that seems to lie in South Africa’s future — awful to contemplate and actively sought by few — is as eagerly to be prayed away as the repression exercised by the government of that country. I think Archbishop Tutu does not so much advocate justice by bloodshed as understand that it is already part of South Africa’s Gethsemane. But I should not presume to interpret him. And I do not hope to try to win over your opinion in one brief letter. Rather, I want to invite your further conversation with the university and the larger national community in this matter.”

Suffice it to say that Hauk got the job. Laney recalls the promise and poise that Hauk exhibited as a student. “When a new position opened up for an assistant secretary of the university in my office, it was a foregone conclusion that he would be the top candidate,” Laney says. “Once in office, he quickly became indispensable and was soon promoted to university secretary and my chief assistant, advising on a range of issues. His auspicious future here had just begun when I left Emory for Korea a short few years later.”

On the day he earned his Emory PhD in 1991, Hauk with his daughter Alexis and son Thomas.

On the day he earned his Emory PhD in 1991, Hauk with his daughter Alexis and son Thomas,

Hauk with Desmond Tutu during the archbishop's tenure as Visiting Woodruff Professor in 1998. Hauk's son Thomas is clearly receiving a strong recommendation from the archbishop.

Hauk with Desmond Tutu during the archbishop's tenure as Visiting Woodruff Professor in 1998. Hauk's son Thomas is clearly receiving a strong recommendation from the archbishop.

“Start small and see where it goes”

Beyond the regular responsibilities Hauk carried out so well, he led several groundbreaking efforts, including the university’s relationship with His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama and the creation of the Emory-Tibet Partnership, now the Center for Contemplative Science and Compassion-Based Ethics.

“From the beginning,” says Geshe Lobsang Tenzin Negi, the co-founder and executive director of the partnership, “the idea of an exchange with Tibetans needed a champion in the central administration. Gary was that person. Without his steadfast work, the partnership would never have achieved the great success it enjoys today.”

The first Emory visit of the Dalai Lama — who spoke at Glenn Memorial Auditorium to a packed house — came in 1987 at the invitation of a faculty member. Ironically, says Hauk, “engaged with work, dissertation, and kids, I didn’t get to see him that day.”

In spring 1995, Hauk fielded a call from investment banker Tom Beard, who was on the Atlanta host committee seeking space in which a large public audience with the Dalai Lama could take place. The Woodruff PE Center became the site, and Hauk was honored to make the introduction of the Dalai Lama.

Hauk, Provost Billy E. Frye and other Emory leaders went to see the Dalai Lama while he was still in town to discuss possibilities for an academic partnership. The Dalai Lama’s response was, “Start small and see where it goes.” By 1998, the Dalai Lama was invited to be commencement speaker, following which he and President William M. Chace signed an agreement unique in American higher education annals. The relationship with the Dalai Lama would deepen further when, in 2007, President Wagner extended an invitation to him to join Emory’s faculty as Presidential Distinguished Professor. It would mark the first, and only, time that the Dalai Lama has accepted an appointment with a Western university.

A career continually sprouting new roots

During James Wagner’s presidency, he and Hauk agreed on a redirection of Hauk’s efforts, deciding that they would seek a full-time university secretary — Rosemary Magee — and have Hauk focus on his duties as deputy to the president and the work to complete the CONTACT (Committee on Traditions and Community Ties) Emory initiative that had begun under Chace. In that regard, Hauk readily agreed to chair what became the Traditions and History Committee.

Student interest was high to revive Charter Day, which the university had stopped observing in 1965. Hauk helped relaunch it in 1999. Five years on, Charter Day gave way to something new: Hauk partnered with Emory College of Arts and Sciences, which was looking for a midyear academic convening — something to energize faculty and students between Convocation and Commencement. Thus was born Founders Week, events celebrating the diversity of academic and campus life.

The former university secretary shares a celebratory smile with the current university secretary, Allison Dykes

The former university secretary shares a celebratory smile with the current university secretary, Allison Dykes

Having planned more than his share of graduations, Hauk was the hands-down choice as committee chair for the university’s 175th anniversary in 2011. Ron Sauder, then vice president for communications and marketing, wryly observes, “For starters, only Gary knew what to call this celebration: our quartoseptcentennial.”

Hauk and a committee of alumni and development staff members selected the 175 Emory makers of history, who were invited to campus for a convocation at the close of the anniversary year. He also worked with Emory videographer Corey Broman-Fulks to produce “Emory History Minutes,” a video series. Says Sauder, “Planning the 175th anniversary brought out Gary’s best qualities — as writer, editor, fact-checker, heritage-keeper and choreographer. And he did so with good humor, erudition lightly worn and unfailing efficiency.”

Truth-teller

To understand the issues that have come before him and be effective adjudicating them, Hauk has asked hard questions, his devotion to Emory notwithstanding. As he stresses, “Unless the university finds ways to delve into its history, there will always be inaccurate stories to disrupt us, and we will always be surprised by the true stories that make us feel uncomfortable.” He continues: “Often it is the unpleasantness of being shaken awake. I learned this from President Laney, who has been an exemplar of moral leadership.”

Hauk led a Journeys of Reconciliation trip to Montana in 2009 that incuded visits to the Crow and Northern Cheyenne reservations as well as conversations with government officials related to race, poverty, health and indigenous culture.

Hauk led a Journeys of Reconciliation trip to Montana in 2009 that incuded visits to the Crow and Northern Cheyenne reservations as well as conversations with government officials related to race, poverty, health and indigenous culture.

Hauk played a significant role in coming to terms with anti-Semitism in Emory’s dental school under the reign of its dean from 1948 to 1961. He worked with others to acknowledge such disturbing individual and institutional behavior and also to recognize the hardship that many endured from these actions. The New York Times in 2012 quoted Hauk saying: “There are often things we regret about our past, but there is the possibility of making amends and of building on the acknowledgment of those things.”

Says Magee, “Gary believes that we all have the capacity to transcend the separate silos and points of view that we naturally inhabit. He has sought to strengthen the ties that connect us by upholding our fundamental values.”

Through the Transforming Community Project, Hauk similarly brought the attention and energies of the entire community to work through differences. He sought and drafted a statement of regret for the history of slavery and racial discrimination, subsequently adopted by the Board of Trustees in 2011.

A distinctive voice

From that first annual report prepared for Laney, Hauk not only has been sure-footed in describing Emory and its arc over the years; he also has been inspirational, solidifying community.

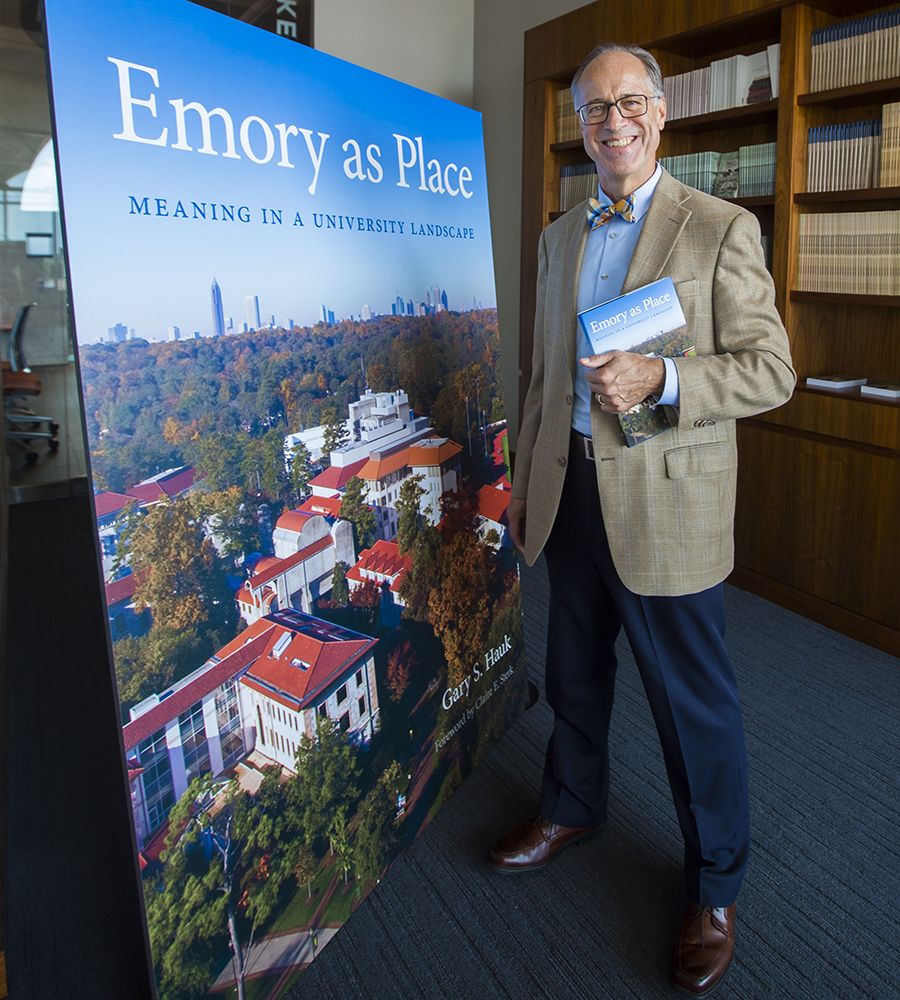

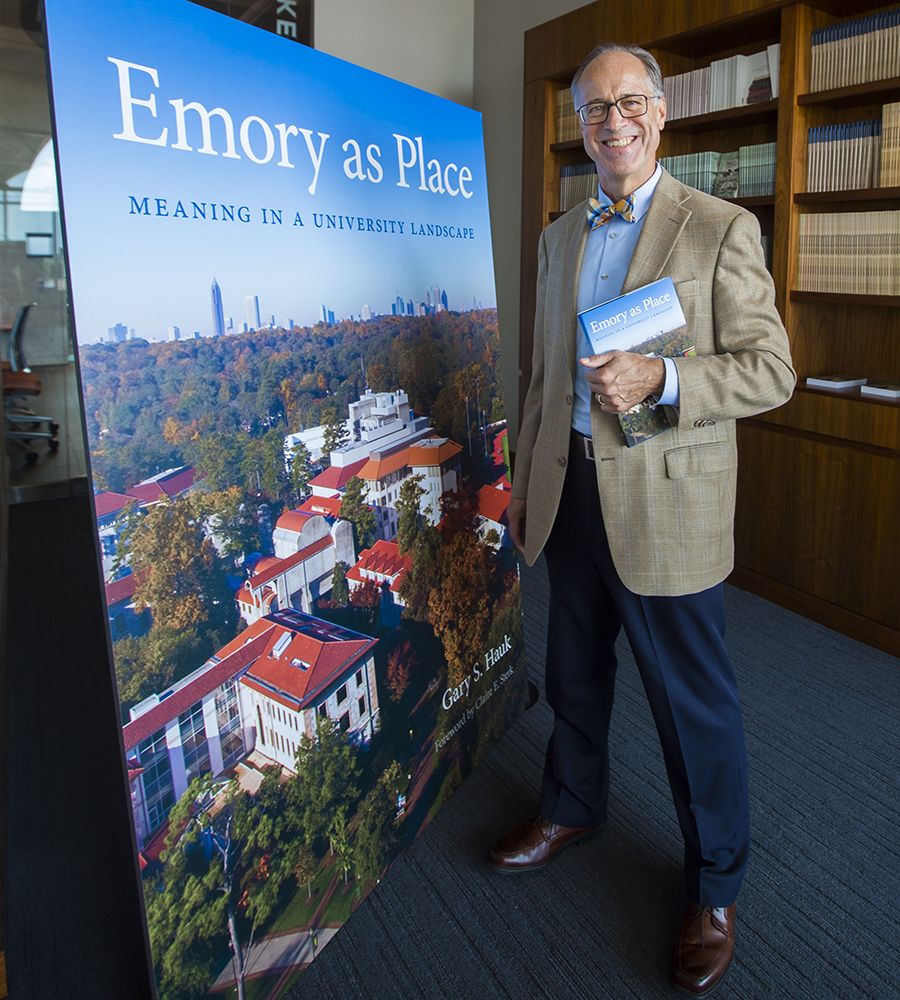

In Hauk's latest book, "Emory as Place," President Sterk contributes a foreword in which she writes, "Gary knew the story behind the story of Emory."

He has authored or edited four books on the history of Emory, including his most recent, “Emory as Place.” Asked how he describes his voice as a writer, Hauk says, “I have aimed always for a kind of understated elegance. I have wanted to be motivating, to communicate that everything we are doing at the university has a moral purpose. There is something above us, calling us.”

One expression of that moral purpose is clear in this excerpt:

“Of protests against injustice there will never be an end because, unfortunately, injustice will always be around to be protested. Yet the opportunity (the responsibility) remains for a university to ensure that the voice of the meek as well as the mighty can be heard. That really is the true work of the university.”

In Hauk's latest book, "Emory as Place," President Sterk contributes a foreword in which she writes, "Gary knew the story behind the story of Emory."

In Hauk's latest book, "Emory as Place," President Sterk contributes a foreword in which she writes, "Gary knew the story behind the story of Emory."

"It’s an odd job, the role of university secretary. It’s nothing that anyone grows up aspiring to be — or even knows about."

—Gary Hauk

One element of the university's 175th anniversary celebration was a relay run between Emory's birthplace on the Oxford campus and the Druid Hills campus.

One element of the university's 175th anniversary celebration was a relay run between Emory's birthplace on the Oxford campus and the Druid Hills campus.

The relay featured an appearance by President Wagner, performances by the university's a cappella groups as well as food and games. Pushball also made a reappearance during anniversary activities.

The relay featured an appearance by President Wagner, performances by the university's a cappella groups as well as food and games. Pushball also made a reappearance during anniversary activities.

What the future holds

Beyond Emory, Hauk will fill his days in a variety of creative ways, continuing, as he has since 2017, as senior editorial consultant and member of the international editorial board of the Emory Center for the Study of Law and Religion’s (CSLR) Cambridge Law and Christianity book series. Hauk especially prizes these duties because they take him back to his days as a religious scholar. Calling him a “brilliant stylist and editor,” CSLR Director John Witte Jr. has asked Hauk to write a history of the center, which will observe its 40th anniversary in 2022.

Hauk also recently was elected chair of the Georgia Humanities Council, whose board he has served on for the past eight years.

Writing projects may include a work of fiction and perhaps a study of Atlanta through the lens of its educational institutions.

Meanwhile, Emory will remain a daily part of his life, as his wife, Sara Haigh Hauk, continues her career in the Advancement and Alumni Engagement Division. The two met at Emory in 2001—ironically, at a retirement party for a colleague.

“Secretary of the Univers”

Throughout a career notable in many ways, surely the signature element of Hauk’s time has been carrying out twin roles as a student of Emory and teacher about Emory.

One element of the university's 175th anniversary celebration was a relay run between Emory's birthplace on the Oxford campus and the Druid Hills campus.

The relay featured an appearance by President Wagner, performances by the university's a cappella groups as well as food and games. Pushball also made a reappearance during anniversary activities.

A bold initiator, Hauk repeatedly stepped forward to provide leadership for plans and programs. At the same time, he generously opened doors, facilitating others’ innovative projects for the common good.

In “Emory as Place,” Hauk pokes fun at the man in the mirror, saying, “It’s an odd job, the role of university secretary. It’s nothing that anyone grows up aspiring to be — or even knows about.” He goes on, describing a piece of mail he received addressed to “Secretary of the Univers” (yes, it did cut off the word “university”). “Now that,” he concludes, “would be a fascinating job.”

He knows, though, that the fascinating job is the one he made here, the one he is about to leave, buoyed by the thanks of a grateful community.

By Susan Carini 04G • Photography: Emory Photo/Video and Gary Hauk

Want to know more? Please visit

Emory University • Emory News Center