High Time for Ticks

Tick-borne diseases are on the rise, from Lyme to alpha-gal. What is the actual danger and how can you avoid these tiny creatures that pack a big bite?

It’s as small and inconspicuous as a freckle, and that’s why you don’t notice it for a while. During its nymph stage, a tick is most likely to be undetected and transmit disease. You go about your days, running errands, going to work, cleaning house—all without knowledge of your little plus-one that you picked up from the camping trip last week.

While you were enjoying the heavily-wooded areas of the mountains, the creature decided to crawl up your pant leg and set up camp, burying its head right underneath your skin. As it feeds on your blood, it might be giving you something in return—perhaps Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrlichia, or alpha-gal allergy.

With the warmer months come yard work, hikes, soccer practice, dog walks, and a rising number of tick-borne illnesses.

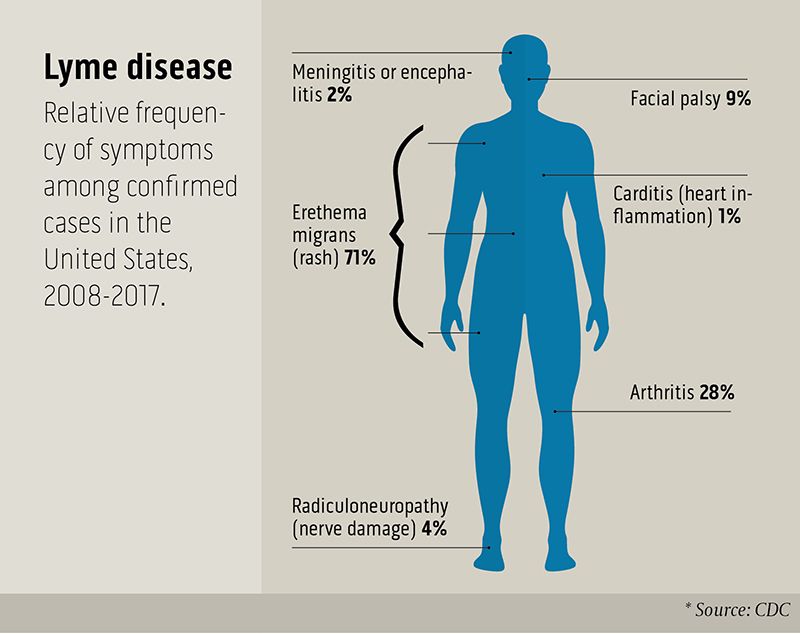

Lyme disease is the most common in the U.S., with more than 30,000 cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention annually—although experts say the actual number of infections is likely 10 times higher, into the hundreds of thousands.

Lyme is most prevalent in New England and the upper Midwest. But cases have been reported all over the U.S.—indeed, around the world. About half the cases occur in people under 21.

Boys between 5 and 9 are the most commonly affected group, perhaps because they spend the most time outside.

Symptoms include muscle fatigue and weakness, low-grade fever, headache, memory fog, and in serious cases, damage to the nerves that cause a tingling or numb sensation.

Marshall Lyon, an infectious disease expert, says people who spend a lot of time outdoors are more likely to have a tick-borne disease, but that everyone should be vigilant, even in their own backyards.

Don’t panic though: Just because you have the symptoms doesn’t mean you have a tick-borne illness. Marshall Lyon, an infectious disease doctor at Emory, sees about 100 patients a year with symptoms similar to Lyme disease, but only a handful test positive for it. “I always ask patients if they have traveled recently,” says Lyon. “If they have been hiking in the northern states, it is much more likely that they have Lyme than, say, a person who lives in Buckhead and their idea of going outside is walking to their car.”

Kendall Lasseter, a recent college graduate from the University of Georgia, is one of Lyon’s patients who tested positive for Lyme.

Lasseter never saw the tick on her and didn’t have the telltale bullseye rash associated with the Lyme tick’s bite.

For Lasseter, it started with migraines about two years ago. “But it wasn’t episodes,” she says. “It was continuous migraines that never went away. Doctors would ask me, ‘When was your last migraine episode?’ And I would try to tell them it was 24/7.”

“I had a list of symptoms, and it seemed like the problems just kept piling up. I had ear pain and hearing loss, neurological problems, and temporary vision loss due to the migraines. I couldn’t pay attention in class because I was so weak and tired all the time,” she says. “I stopped going to class because I couldn’t focus. Some doctors told me I was just stressed at school, but I knew something was wrong.”

A doctor in south Georgia diagnosed Lasseter with Lyme disease. She was referred to Lyon after seeing numerous other doctors.

“Dr. Lyon ran some more tests to confirm I had Lyme, and then I was put on antibiotics,” she says. “I’m definitely doing better now, but I still have neurological problems and just an overall tired feeling.”

Lasseter doesn’t know where she picked up the tick that gave her Lyme disease.

She had traveled to London, which is her best guess as to where she got bitten. Ticks transmitting Lyme have been found in parks within the city of London, and reported cases are on the rise there as elsewhere.

A sampling of tick diseases and allergies

Named for Old Lyme, Connecticut, where the disease was first recognized in 1975, Lyme disease is transmitted by the deer tick, also called the black-legged tick.

To call it a deer tick is a bit of a misnomer, says Lyon. “These ticks usually feed off of the white-footed mouse, not deer. This mouse is more common in the northern states, which is why Lyme is more common there. The mice carry Lyme, which is transmitted to the tick when it bites the mouse and then can be transmitted to humans through infected ticks.”

With Lyme disease, the symptoms are many and varied. People who have been bitten by an infected tick often have a “bullseye” rash, named after the darkening red in the middle of a paler red ring that expands. (Like Lasseter, however, some people with Lyme never get this rash.) People with Lyme will often feel sluggish and tired, with muscle weakness and fatigue described as “flu-like.” Left untreated, the Lyme spirochete (spiral-shaped bacteria) can affect the heart, causing irregularities in rhythm, and can attack the nervous system, spinal fluid, and brain, causing “Lyme meningitis.”

Treatment for Lyme disease is a round of antibiotics for a few weeks to a month. If the disease is severe, patients receive IV antibiotics.

In severe cases, post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome, often including neurological symptoms, can linger for months to years. “I tell patients that if they were in an accident where nerves were cut off or damaged, the nerve will grow back at about an inch per month, so it takes a while to heal,” says Lyon. “With Lyme disease, there are often two parts to getting better. There’s the treatment, where we use antibiotics to kill the bacteria, and then there’s the healing phase, which can take a really long time.”

Ehrlichia, scientifically known as human monocytic ehrlichiosis, is more common in the southeastern U.S. and is transmitted by the lone star tick (the females have a distinctive white patch on their backs). Ehrlichia is an acute infection and isn’t likely to cause any long-term effects. Symptoms of ehrlichia resemble that of an infection: fever and chills, headache, and vomiting are the most common.

Ehrlichia is treated with antibiotics and symptoms can last up to a few weeks. If treatment is delayed, ehrlichia can cause severe illness, especially in the very old or very young, or those with weakened immune systems.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is similar to ehrlichia in that it causes a fever and headache, and a rash usually develops within two to four days (the rash can range from red splotches to pinpoint dots). But Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be much more serious than ehrlichia if left untreated, even causing deaths from bacterial infection. Rocky Mountain spotted fever is treated with a few weeks of antibiotics and is usually quickly cured if caught early, but can be deadly if not treated early with the right antibiotic.

Alpha-gal is transmitted by the lone star tick, which is mostly found in the southeastern U.S., and can make people who are infected allergic to red meat. Jennifer Shih, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at Emory and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, has seen a few cases of this rare allergy.

“The allergy itself is not well understood,” says Shih. “Alpha-gal is an allergy to the carbohydrate ‘galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose,’ or alpha-gal for short. This is strange in itself because 90 percent of allergies are caused by proteins, but this is caused by the carbohydrate in the tick’s gut.”

“What happens is the tick bites a deer and gets infected, then bites a human,” she says. “This is the patient’s exposure to alpha-gal. Then, when the patient eats red meat, they will have an allergic reaction.”

Stranger still, the symptoms of the allergic reaction—vomiting, hives, and occasional anaphylaxis—occur hours after eating the red meat. (Most allergic reactions are almost instantaneous.) One theory is that breaking down a carbohydrate versus a protein may delay reaction time.

Shih says that people with alpha-gal allergy can consume seafood, poultry, and eggs—the allergy specifically is to red meat, including beef, pork, lamb, and deer, and sometimes even milk and butter (which contain only small amounts of alpha-gal).

“There are no cases I know of where the allergy has been cured and the allergic reaction has just ‘gone away,’ ” says Shih. “But there’s so much we don’t know yet.”

One way to avoid ticks while enjoying the great outdoors is to tuck your pants in your socks. “It may not be fashionable, but it is practical,” says Emory infectious disease physician Marshall Lyon.

Tick avoidance

Precautions to avoid tick bites include the following: Use EPA-registered insect repellent when in woods, in underbrush, on sports fields, or in your own yard. Wear long pants and long sleeves. After being outside, always check for ticks on people and pets. Use a mirror to check your back. Shower within two hours of coming in from tick-infested areas. EHD

Infectious disease physician Marshall Lyon, above, sees patients with Lyme and other tick-borne diseases and recently recorded a video to call attention to tick dangers and prevention. Watch at emry.link/ticksvid1.

Infectious disease physician Marshall Lyon, above, sees patients with Lyme and other tick-borne diseases and recently recorded a video to call attention to tick dangers and prevention. Watch at emry.link/ticksvid1.

One way to avoid ticks while enjoying the great outdoors is to tuck your pants in your socks. “It may not be fashionable, but it is practical,” says Emory infectious disease physician Marshall Lyon.

One way to avoid ticks while enjoying the great outdoors is to tuck your pants in your socks. “It may not be fashionable, but it is practical,” says Emory infectious disease physician Marshall Lyon.

A Tick’s Best Friend

One of the many reasons pets, especially dogs, should be on a regular regimen of flea and tick medication is that they too can become infected and ill from tick-borne disease. Your four-legged friends are susceptible to many of these diseases, including Lyme disease, canine ehrlichiosis, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and bartonellosis, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever, to name a few. Dogs that have become infected with Lyme disease will act lethargic and may experience loss of appetite, fever, and fatigue. Other tick-borne diseases, like anaplasmosis, may cause your dog to experience vomiting, diarrhea, or seizures. While no method offers 100 percent protection, veterinarians suggest a tick collar or medication for your dog, especially during spring and summer. Be diligent in checking your dogs for ticks when outside.