HONORING

Camille

On a warm, breezy day this past April, a World War I nurse named Camille O’Brien came to life as dozens of people gathered in Atlanta’s Greenwood Cemetery to commemorate the 100th anniversary of her death.

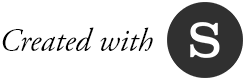

During the war, O’Brien, who grew up in a small town in Georgia, served with the Emory Unit in Blois, France. Largely staffed by faculty physicians and hospital nurses from Emory, the unit operated Base Hospital 43, where O’Brien worked long hours caring for sick and wounded soldiers. After becoming ill, she died at the hospital on April 18, 1919.

O’Brien eventually was laid to rest in Greenwood Cemetery. The site remained unmarked until this year, when Michael Hitt, a retired policeman turned historian from Roswell, Georgia, arranged for a marker to be placed on her grave.

“Camille represents everything you want in a nurse,” says Hitt. “She put her life second to her patients to the point that it cost her life. She was the only member of the Emory Unit who never returned.”

Hitt learned about O’Brien just over a year ago, when he met William Cawthon, a retired insurance claims adjustor from Roswell. Now 84, Cawthon wanted to find a permanent home for several personal items that had belonged to O’Brien, his great aunt.

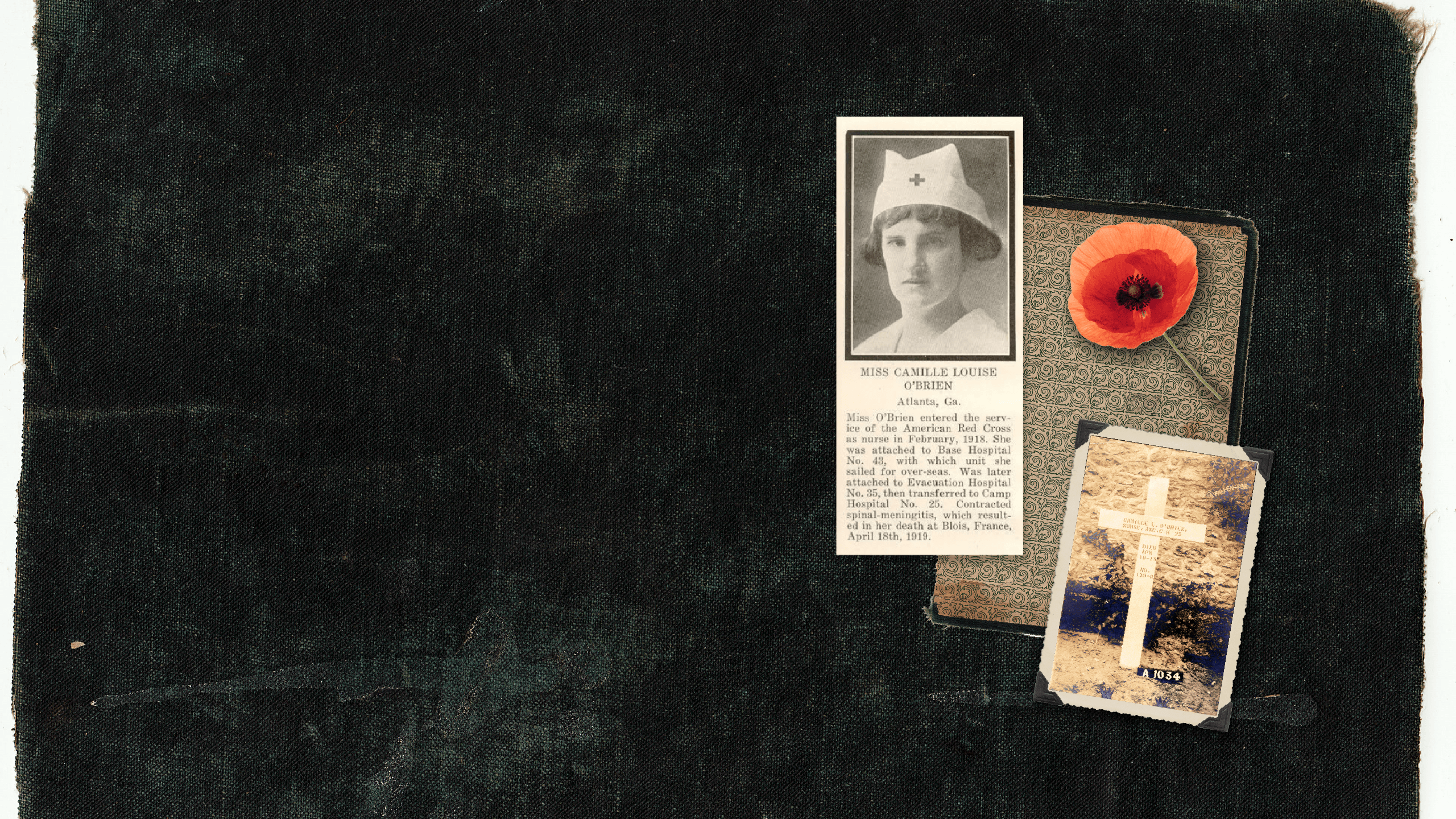

Cawthon knew little about her, other than that she had died while serving as a nurse in WWI France and that his mother was named for her. No photos of his Aunt Camille existed. Most of her belongings had been stored in a suitcase up in the attic of his family’s home. Among them was a yellowed letter, sent to O’Brien’s sister (and Cawthon’s future grandmother) when she died, and a photograph showing her marked grave in a cemetery near Base Hospital 43 in Blois.

Hitt was intrigued. With Cawthon’s permission, he arranged for O’Brien’s personal effects to be donated to the Atlanta History Center. He also thought it fitting that a simple ceremony be held at O’Brien’s grave in France to mark the 100th anniversary of her death in 2019. An acquaintance of Hitt’s on the Georgia World War I Centennial Commission reached out to the French Embassy for assistance.

“That’s when we learned that Camille’s body was brought back from France to Atlanta in 1921,” says Hitt. The question was, where was she buried?”

Ever the detective, Hitt searched for clues. He consulted ancestry.com, state and city census records, Atlanta newspaper archives, and historic collections in Emory’s Woodruff Health Sciences Center Library (including the book History of the Emory Unit, U.S. Army, 1917-1919), and the Atlanta History Center. He also attended a lecture on the Emory Unit given by Render Davis 71C. His grandfather, Emory medical professor Edward C. Davis, organized and led the Emory Unit from 1917 to 1919.

“It was just like recreating a crime scene,” says Hitt. “No detail was too small to understand what happened to Camille.”

He found enough information to fill a thick white binder documenting her life.

A life story unfolds

Camille Louise O’Brien was born on November 9, 1883, in Warren County, Georgia. One of 13 children (10 boys and three girls) in an Irish Catholic family, she grew up in Barnett, a small town about 100 miles east of Atlanta. At its peak, Barnett had a railroad depot, several stores, many houses, and at least one church. The town is gone now except for Barnett Methodist, a white wooden structure that has been restored.

Ed O’Brien, Camille’s father, was a railroad man, postmaster, and mercantile business owner. From 1900 to 1901, daughter Camille attended the University of Georgia (UGA). She lived and studied at Georgia College in Milledgeville—female students weren’t allowed on the main UGA campus in Athens.

By 1910, census records showed her living in Atlanta with her aging father, who died in 1915. While caring for him, O’Brien entered Saint Joseph’s Infirmary School of Nursing in 1913. She graduated in 1916 and practiced nursing at Saint Joseph’s Infirmary (now Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital) for two years.

Patriotic fever ran high after the United States entered World War I against Germany in 1917. O’Brien joined the Army Nurse Corps in early 1918 and was transferred to the Emory Unit, led by Davis. In February, she was sent to Camp Gordon—the site of today’s Peachtree-DeKalb Airport—where Emory Unit physicians, nurses, and staff trained. They learned how to manage a military hospital and prepared for the grim realities of war—gas attacks, infectious disease, gunshot wounds, and amputations. Many learned to speak basic French.

In May, the Emory Unit nurses left Camp Gordon and boarded a train to New Jersey. On July 4, they marched with 15,000 Red Cross nurses in a parade in New York City, where O’Brien received a large Red Cross pin in a box from Tiffany & Co.

The nurses then traveled by train to Montreal, where they boarded the Durham Castle, a troop transport ship. On July 20, the ship set sail from Halifax, Nova Scotia, in a convoy to Wales. During the voyage, the nurses witnessed three attacks by German submarines. When one of the U-boats surfaced right behind the ship, the gunner aboard was said to have gotten it.

After the Durham Castle arrived in Wales, the nurses were transferred to South Hampton, England, where they set sail again on the Gilford Castle, a hospital ship bound for Le Havre, France. From there, they traveled by train to the medieval town of Blois, where Base Hospital 43 had become operational in July, a month before the nurses—100 in all—arrived on August 6.

Base Hospital 43 occupied several buildings, including Annex Ecole Superieure, a school building with the largest hospital bed capacity. There, O’Brien and other nurses assisted Lieutenant Colonel Frank Boland, chief surgeon and an Emory School of Medicine faculty member.

Initially, Base Hospital 43 was outfitted for 500 patients but housed up to 2,341 patients at one time. During the hospital’s six months and 18 days of operation, doctors and nurses treated 9,034 patients. Total deaths numbered 102. The Emory Unit, The Atlanta Journal reported at the time, had the lowest mortality rate of any hospital in France.

Although Armistice Day was declared on November 11, 1918, the Emory Unit was not ordered home until January 21, 1919. Several nurses, including O’Brien, volunteered to stay behind to care for soldiers too injured or sick for transport. At one point, she caught the Spanish flu but continued working. Too many soldiers needed care, she told her superiors.

O’Brien recovered. Later, on April 2, she complained of a headache but refused to see a doctor, her nursing superior later recounted. O’Brien became ill once more, this time with spinal meningitis. Two nurses watched over her day and night as she slipped in and out of consciousness. On April 18, 1919, O’Brien died in the hospital where she had nursed so many soldiers. She was 35 years old.

News spreads back home

Back in Atlanta, news of O’Brien’s death spread quickly. One newspaper story quoted Frank Boland, the surgeon with whom O’Brien had worked at Base Hospital 43:

Members of American Legion Post 143, Carrollton, Georgia, post colors during the ceremony for Camille O’Brien at Greenwood Cemetery.

“It distressed me greatly,” said Colonel Boland, “to learn of the death of this accomplished and lovable young woman. She was one of the finest nurses with the Emory unit and one of the hardest workers I ever saw. She was loved by all the men and took a personal interest in every case that she attended. Miss O’Brien was at the very top of the list and I’m sure no more popular or capable woman served in France.”

Michael Hitt, wearing a World War I uniform, and William Cawthon, O’Brien’s great-nephew, stand at her newly marked grave on the 100th anniversary of her death this past April.

Caroline Dantzler, the chief nurse at Base Hospital 43, sent a two-page, typewritten letter to Gladys Harbin, O’Brien’s married sister, in Decatur, Georgia. Dantzler wrote:

“She was a soldier true and on the 19th Saturday afternoon we buried her in line and beside our soldier boys with full military honors. Possibly you, her people may feel hurt more keenly that she shall go among strangers. But the ravages of this war has brought about a bond that is unexplainable. And you can never realize what it meant to us to give her up.”

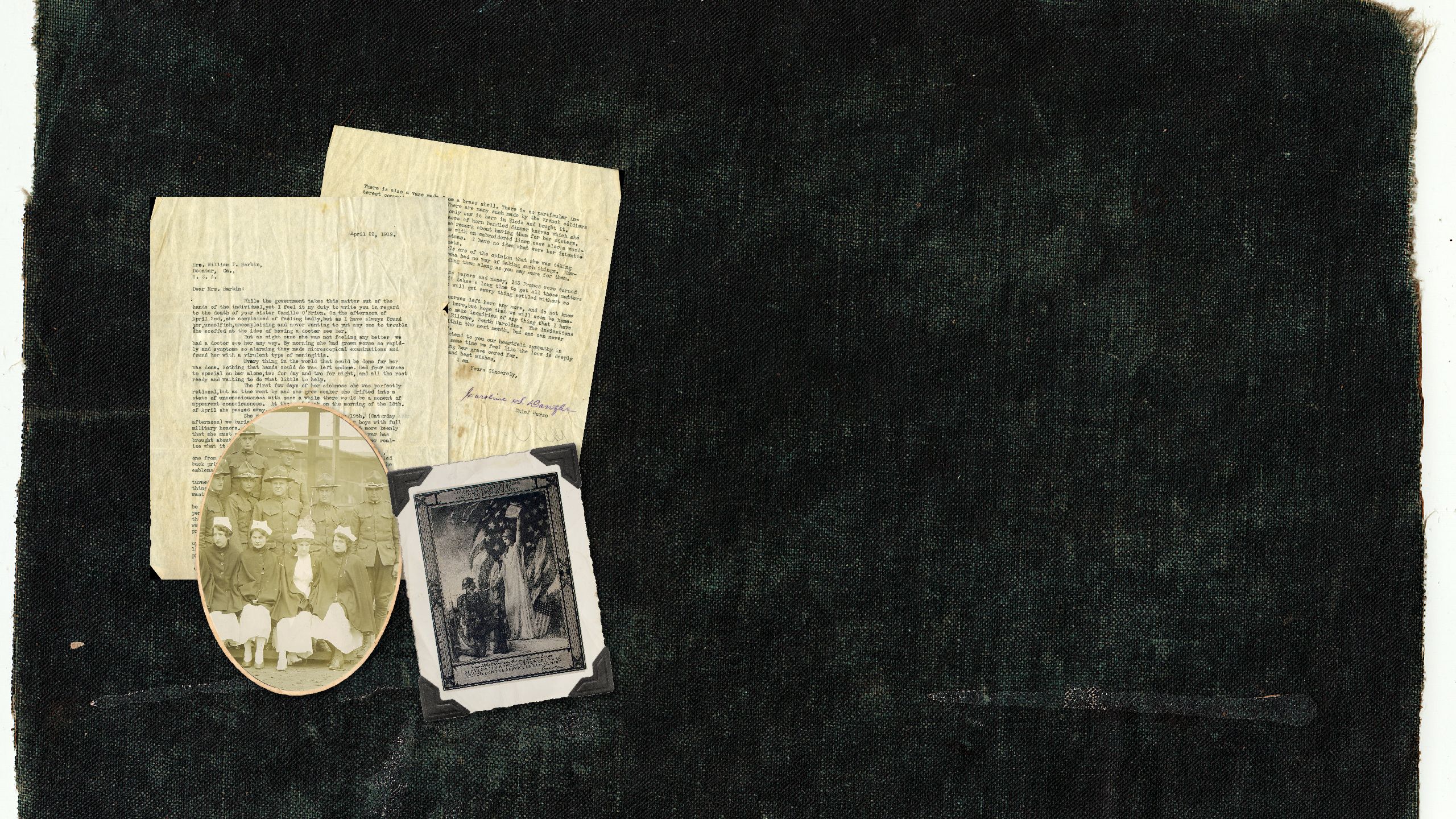

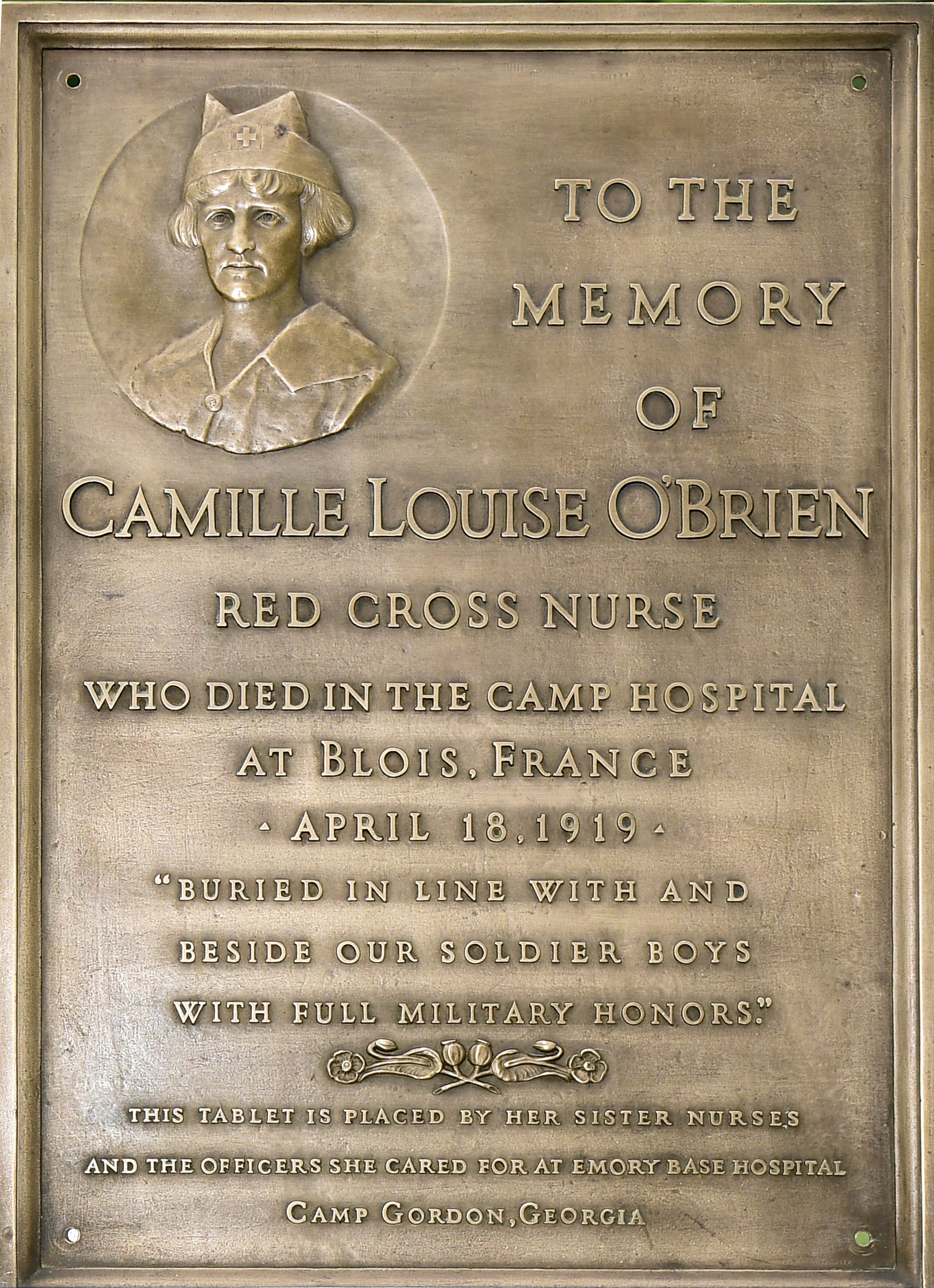

This newly restored plaque was originally commissioned by the Emory Unit, five months after her death in 1919.

Dantzler’s letter also mentioned O’Brien’s personal effects, to be sent to Harbin by the War Department. Among the items: a Red Cross pin and two large brass artillery shells—one German, one French—that O’Brien had picked up near the battlefields of Verdun. (Years later, Cawthon’s family used the German artillery case as an umbrella stand; the French artillery case, fashioned into a decorative piece known as trench art, held matches for the fireplace).

In September 1919, five months after O’Brien’s death, the Emory Unit unveiled a plaque in her honor at a building occupied by Emory School of Medicine near Grady Memorial Hospital. Two years later, O’Brien made headline news again when her family brought her body back from France for reburial. Her coffin, draped in a U.S. flag and guarded by an Army escort, arrived by train in Atlanta’s Terminal Station on December 29, 1921.

O’Brien received this American Red Cross pin in New York.

O’Brien received this American Red Cross pin in New York.

At her memorial service the following day, Jackson L. Allgood, the chaplain for the Emory Unit, recalled how O’Brien worked during the days of fighting despite being ill. When admonished, she was said to have replied, “I cannot rest while men are being brought in faster than their wounds can be dressed.”

O’Brien was laid to rest in Greenwood Cemetery, next to her older brother, Joseph. The DeKalb County chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) offered to erect a headstone on her grave. When the family decided on a larger marker, the DAR could not afford the cost. O’Brien’s grave remained unmarked for nearly a century.

Members of American Legion Post 143, Carrollton, Georgia, post colors during the ceremony for Camille O’Brien at Greenwood Cemetery.

Members of American Legion Post 143, Carrollton, Georgia, post colors during the ceremony for Camille O’Brien at Greenwood Cemetery.

Michael Hitt, wearing a World War I uniform, and William Cawthon, O’Brien’s great-nephew, stand at her newly marked grave on the 100th anniversary of her death this past April.

Michael Hitt, wearing a World War I uniform, and William Cawthon, O’Brien’s great-nephew, stand at her newly marked grave on the 100th anniversary of her death this past April.

This newly restored plaque was originally commissioned by the Emory Unit, five months after her death in 1919.

This newly restored plaque was originally commissioned by the Emory Unit, five months after her death in 1919.

A day of remembrance

When Hitt learned why O’Brien’s grave was never marked, he set out to finish the task. He visited the sexton at Greenwood Cemetery to determine where she was buried, arranged for a marker to be laid, and organized a ceremony to unveil it on the 100th anniversary of her death. If it weren’t for Hitt, Cawthon would never have known that his great aunt had been brought back from France and reburied in Atlanta.

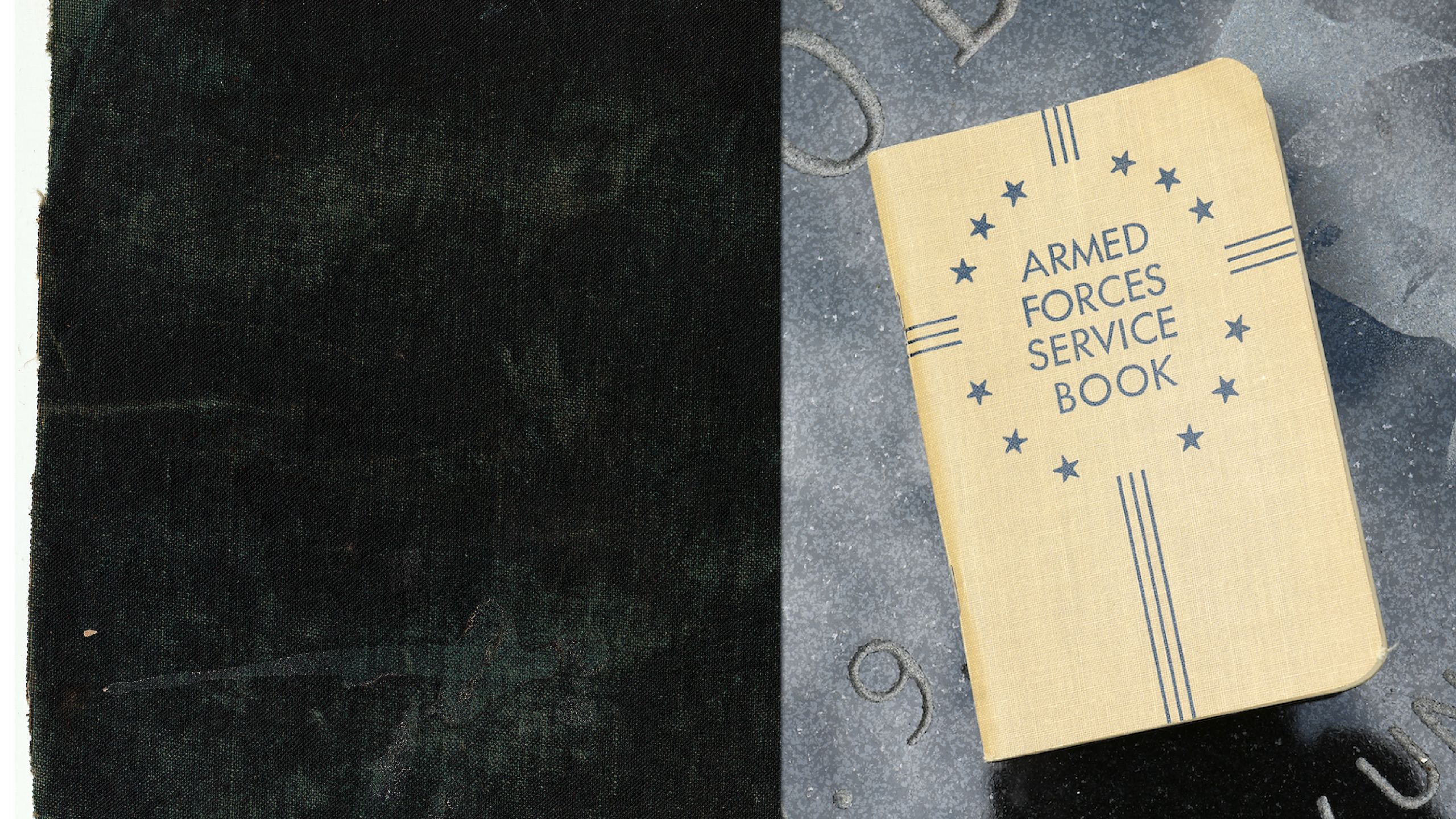

Woody Spackman, retired Emory Healthcare chaplain, used this World War I prayer book (shown right) during the commemoration ceremony for O’Brien.

Woody Spackman, retired Emory Healthcare chaplain, used this World War I prayer book (shown right) during the commemoration ceremony for O’Brien.

“My family didn’t talk much about Camille,” Cawthon says. “I remember very little about her, other than the items in her suitcase. It’s unbelievable what Michael found when he started digging around. He showed me her picture for the first time.”

Hitt was able to identify O’Brien in a photo that Render Davis uses in talks about the Emory Unit. The huge panorama photo shows more than 200 unit members at Camp Gordon, including his grandfather Edward Davis. Pictured in the front row are the nurses. All are seated, including O’Brien, who is second from the right. When the photographer snapped the photo, O’Brien was caught looking down at her nurse’s cape, apparently blown open by a breeze.

Several people paused to look at the panorama photo, displayed at the commemoration ceremony for O’Brien on April 18 this year. Robin Lnenicka, a longtime nurse at Emory University Hospital, was among those who had come to pay her respects. She paused before explaining why she had come.

“Camille O’Brien left everything she knew behind to care for soldiers in a war zone,” says Lnenicka. “She did not know what she would face. She put her patients first. That is the legacy for nurses today.”

Robin Lnenicka and her husband, Wade (far left), attend the ceremony with members of American Legion Post 160 from Smyrna, Georgia. Robin is a nurse at Emory University Hospital.

Robin Lnenicka and her husband, Wade (far left), attend the ceremony with members of American Legion Post 160 from Smyrna, Georgia. Robin is a nurse at Emory University Hospital.

During the ceremony, Lnenicka and other Emory nurses stood with attendees from the American Legion, the DAR, the Georgia World War I Centennial Commission, the American Red Cross, the Patriot Riders of Georgia, the French and Irish embassies, and H.M. Patterson & Son Funeral Directors, which covered the cost of O’Brien’s marker.

Hitt spoke during the ceremony, as did Woody Spackman, retired Emory Healthcare chaplain, and Davis, who re-unveiled the Emory Unit plaque honoring O’Brien, now refurbished. For years, the plaque was hidden from view in a basement hallway at Emory University Hospital. It will now hang in a prominent place at the hospital for all to see.

As the ceremony ended, O’Brien’s black granite grave marker, etched with her likeness, was unveiled, completing a task that should have happened long ago.

Some of the tributes commemorating Camille O'Brien 100 years after her death during World War I.

Some of the tributes commemorating Camille O'Brien 100 years after her death during World War I.

“It’s the end of the story,” says Hitt, dressed in a WWI uniform for the occasion. “We’re finally giving Camille her due by remembering her with honor.”

By Pam Auchmutey, Photos by Jack Kearse, Design by Angela Vellino. Historic images courtesy of Woodruff Health Sciences Center Library/Emory University, the Atlanta History Center, and Michael Hitt.

To learn more, visit

Emory University

Emory News Center