Bitter, salty, sour, sweet

After cancer, he can taste them all

On your mark, get set, fight cancer.

On Saturday, Oct. 5, more than 3,200 participants joined in the annual Winship Win the Fight 5K, to raise funds for innovative cancer research at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University.

Now in its ninth year, the event has raised more than $4.9 million to support cancer research, and there's still time for you to help achieve this year's goal of $900,000. Learn how you can donate.

For chef Scott Adair, the diagnosis was a worst-case scenario. In 2014, he kept feeling short of breath when playing paintball with his son. “I thought I had inflamed lymph nodes or something,” he remembers. Instead, doctors gave the 49-year-old dad the news that there was a major mass in the back of his throat. A surgeon near Adair’s home in Asheville, North Carolina, told the chef that the only answer was surgery to remove his jawbone and almost half his tongue.

The news put Adair into a state of shock. “My greatest tool is my tongue,” Adair says. “I make a living using my taste buds.” Would he really have to lose his tongue to save his life?

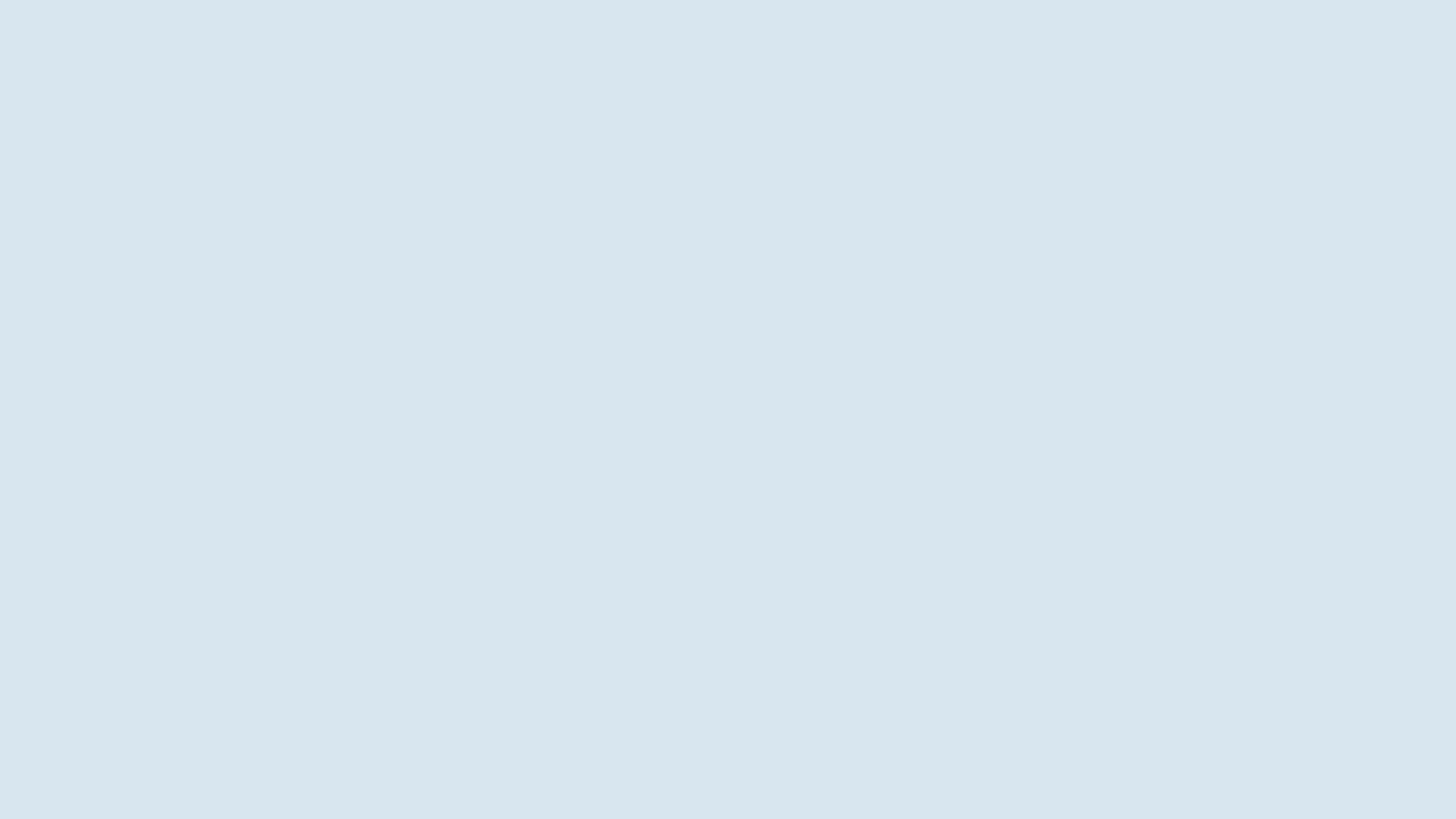

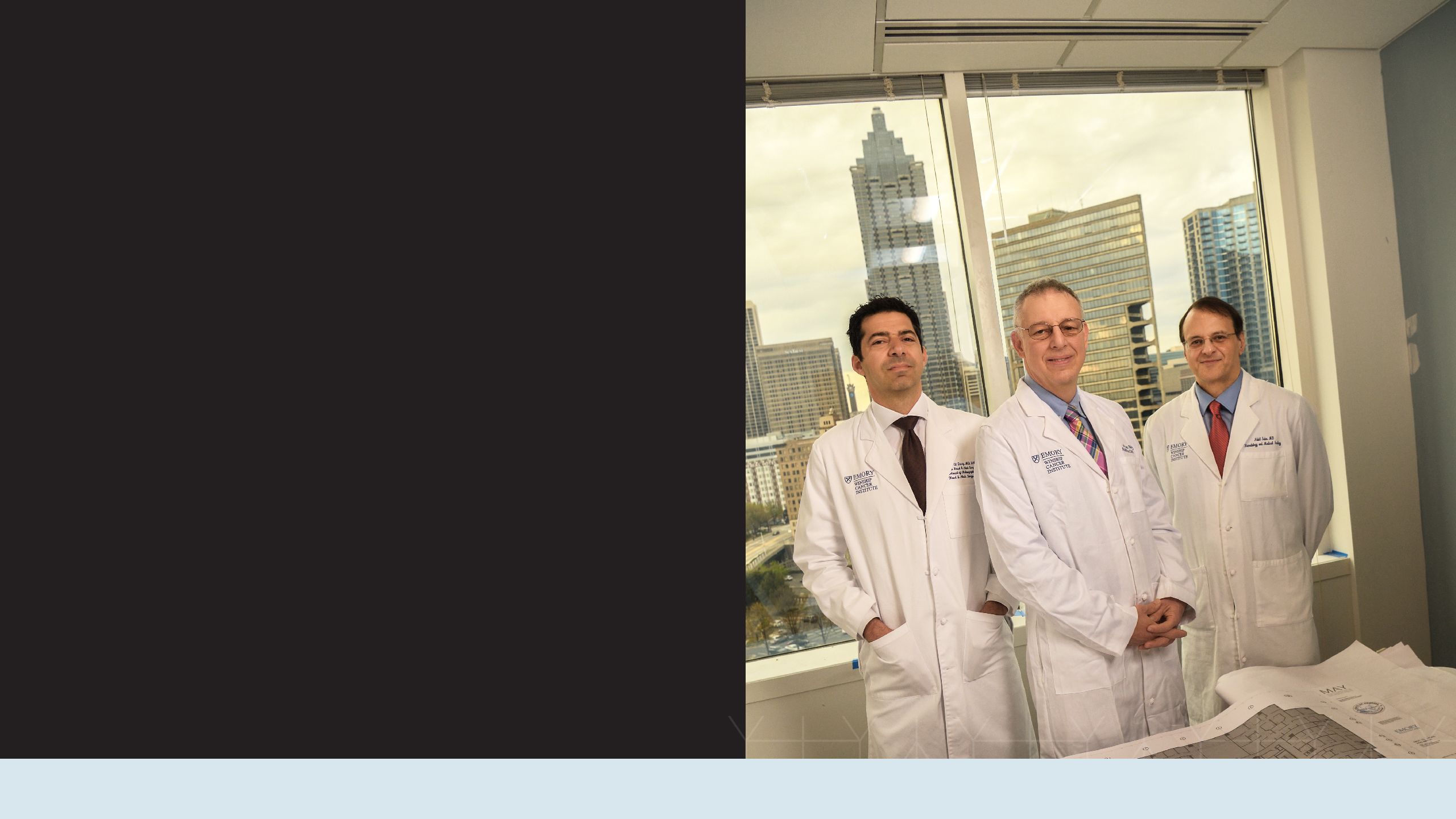

When Mark El-Deiry tells people he’s director of the Head and Neck Oncology Surgery Center at Emory's Winship Cancer Institute, he invariably gets asked what that means.

“I tell them head and neck cancer includes all cancer above the collarbone, except brain tumors or cancer that starts in the eye,” says El-Deiry. He and his colleagues treat cancers centered around the mouth, throat, or nasal passages: tongue cancer and cancers of the larynx, sinuses, nasal cavities, oral cavity (mouth) or salivary glands.

Given their sensitive location, these cancers are difficult to treat and often debilitating. Unless doctors address them with the most advanced and targeted treatments, head and neck cancers also have the potential to be disfiguring and can impair a person’s ability to swallow, taste, smell and talk. But increasingly, there are alternatives. Many head and neck cancers can be treated using noninvasive and less-scarring technologies.

Now, as Winship’s head and neck experts move into a new multidisciplinary clinic at Emory University Hospital Midtown (EUHM), they’re even more determined to catch and treat head and neck cancer for patients throughout Georgia and the Southeast.

Adair met El-Deiry when he came to Winship for a second opinion. Would the chef have to lose his tongue? The answer was no. Adair was evaluated by Nabil F. Saba, director of Winship’s Head and Neck Cancer Medical Oncology Program, and radiation oncologist Jonathan Beitler, and the Winship team gave him the good news that advanced radiation and chemotherapy would be enough. They warned him, though, that he’d lose his taste buds, at least for a period of time.

Adair and his family moved to Atlanta for seven months so that Adair could undergo radiation and chemotherapy at Winship. The treatment worked, but Adair spent several months waiting nervously for his taste buds to return. They came back one at a time: first, salt. Then bitter, then sour. The last one was sweet. “I knew I was ok when I took a bite of chocolate cake and it tasted so great!”

Today, Adair is back in Asheville, cancer-free, and pursuing his passion as a chef. He says his sense of taste is stronger than ever. “I can pinpoint all kinds of great flavor notes,” he says with relief. “I’m back to doing the job I love.”

"I've been a chef for 28 years. It's my whole life. It's everything I do. I love it," says Scott Adair. He started in restaurant kitchens but now travels the country discovering the latest food trends as an executive chef for SupHerb Farms.

"I've been a chef for 28 years. It's my whole life. It's everything I do. I love it," says Scott Adair. He started in restaurant kitchens but now travels the country discovering the latest food trends as an executive chef for SupHerb Farms.

Adair was lucky his diagnosis happened quickly. In 2017, Rayford Cleveland, a retired mechanist, began noticing his voice was hoarse. Over the course of months, it became more and more hoarse. “My voice kept getting worse and worse until I couldn’t even talk,” he remembers. His doctors gave him antibiotics that didn’t help. By Thanksgiving, his voice was barely audible.

If chef Scott Adair is a new face of head and neck cancer—young with limited exposure to known carcinogens—Rayford Cleveland may fit a more traditional profile.

Until about 20 years ago, most head and neck cancers were associated with tobacco and other carcinogens, and largely occurred in adults over the age of 60. Cleveland, now in his 70s, smoked cigarettes and was exposed to the toxin Agent Orange while serving in the military in Vietnam.

Therapist Hannah Cornett checks Rayford Cleveland and gives some tips on swallowing technique.

Therapist Hannah Cornett checks Rayford Cleveland and gives some tips on swallowing technique.

Despite his risk factors, Cleveland was misdiagnosed for months as multiple doctors tried to make sense of his hoarseness. Finally he was diagnosed with stage III cancer of the vocal cords and came to Winship for treatment.

If Cleveland had been given the same diagnosis 20 years ago, he most likely would have undergone surgery to remove his larynx, making speech incredibly challenging. Winship doctors didn’t think invasive surgery was necessary but also didn’t think Cleveland could withstand chemotherapy. Immunotherapy specialist Nabil Saba explains, “Because he is older than 70, he is considered a somewhat high risk for the standard chemotherapy. Instead, we looked for an option that would be better tolerated for him.”

Winship doctors found a clinical trial combining radiation and immunotherapy that was a good fit for Cleveland. Immunotherapy works by enhancing the immune system’s ability to recognize abnormal cancer cells and kill them, and it can cause fewer and less intense side effects than chemotherapy and radiation.

Saba says immunotherapy is proving to be a literal lifesaver (and quality-of-life saver) for many patients like Cleveland whose bodies may not tolerate chemotherapy or for those whose cancer has been unresponsive to traditional chemotherapy and radiation.

“Head and neck cancer is very difficult to treat and has a significant mortality rate—especially if the cancer comes back after radiation and chemotherapy,” says Saba. “But now with immunotherapy we have a novel treatment that improves survival rates while preserving quality of life.”

Cleveland finished his treatment at the end of 2018 and is now disease-free. “Finding out the cancer was gone was one of the greatest moments I’d ever had,” he says. “I’m just so thankful.” He’s back to cooking, gardening, and doing his own yard work and housework—as well as speaking with ease.

Statistics from the National Cancer Institute.

Statistics from the National Cancer Institute.

Both Cleveland and his doctor are optimistic about the future. “I am hoping that Mr. Cleveland will have long-term disease control and cure,” says Saba.

While immunotherapy is still primarily being used for patients who’ve already tried other treatments, Saba is continuing research efforts through clinical trials combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy and radiation. He says that immunotherapy will likely become the new standard of treatment for patients with newly diagnosed or early stage diagnoses in the near future. “It’s changing the landscape of treatment completely,” says Saba.

Research advances leading to effective, less toxic treatments like immunotherapy promise long-term control of disease, even for some patients who were deemed incurable as recently as a few years ago. Winship’s team is at the forefront of new treatments that improve longevity and have better quality-of life outcomes. Proton therapy is another advanced treatment that can effectively treat some head and neck cancer patients and preserve quality of life.

Winship started treating patients at the Emory Proton Therapy Center in late 2018 and is the only cancer center in Georgia offering proton therapy. Proton therapy is a very precise form of radiation that targets the tumor and has minimal effect on healthy tissues surrounding it. Mark McDonald, Winship radiation oncologist and medical director of the Emory Proton Therapy Center, says proton therapy can reduce long-term side effects like dry mouth that can affect a patient’s ability to talk, swallow and taste.

Winship radiation oncologist Jonathan Beitler treats head and neck cancer patients with both traditional radiation therapies and with proton therapy (Scott Adair is one of his patients but did not have proton therapy), so he divides his time between EUHM and the Emory Proton Therapy Center. He says proton therapy has great potential for patients whose cancer has come back after chemotherapy and traditional radiation. “If someone’s cancer comes back, most of the time the recurrences are near critical areas, making surgery impossible,” he explains. “But the precision with which we can deliver proton therapy to address the recurrence is breathtaking.”

Winship specialists, who care for more than 50 percent of head and neck cancer patients from throughout the state, often diagnose cancers that other doctors miss. Part of the challenge of accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment relates to shifting risk factors.

The good news is that fewer people are smoking cigarettes, the most common cause of head and neck cancers. The not-so-great-news is that human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection, is now a leading cause of head and neck cancer (see HPV vaccination sidebar, end of story).

The CDC reports that HPV is so common that almost all people who are sexually active may get it at some point, though most people are asymptomatic. At the time of his diagnosis, Adair discovered that his cancer was HPV-related. “I didn’t even know I had HPV,” recalls Adair now. “I was blown away. I didn’t know what to think.”

Adair may have been surprised by the link between HPV and his cancer diagnosis, but Winship doctors are not. “Most adults who are sexually active have probably been exposed to the virus and never know it,” says El-Deiry. Research about HPV-related head and neck cancers is advancing rapidly as scientists, including those at Winship, collect more and more data. Today HPV-related head and neck cancers are considered among the most treatable.

Specialization enables the team to more quickly and correctly diagnose patients, implement an effective treatment plan, and achieve better outcomes. “If you see two head and neck patients a year, you won’t be as experienced as if you’re seeing 15 to 20 head and neck patients per day,” explains Saba.

Beitler adds, “We have an enormous team with a depth and breadth that is very hard to reproduce at a small hospital.”

The head and neck cancer specialists at Winship make the most of that depth and breadth through weekly multidisciplinary meetings called tumor boards, where they work together to review each patient’s care. “Head and neck cancer needs collaboration between experts,” explains Saba. “Together, we need to agree on a treatment plan.”

While Beitler, Saba and El-Deiry all have their specialties within the head and neck cancer treatment team, all three are united in their efforts to improve patient experience and quality of life after treatment.

“A lot of times when a patient comes in with cancer, the anxiety level is super high,” says Beitler. “It’s literally a life-threatening problem and anything we can do to make the process easier is important. We try to be responsive to patients on the physical level as well as the emotional level.”

For many patients, physician collaboration makes the difference between a cohesive, comprehensible treatment plan, and confusion. Studies show that multidisciplinary clinics where patients see all team members in one day and in one place result in better clinical outcomes.

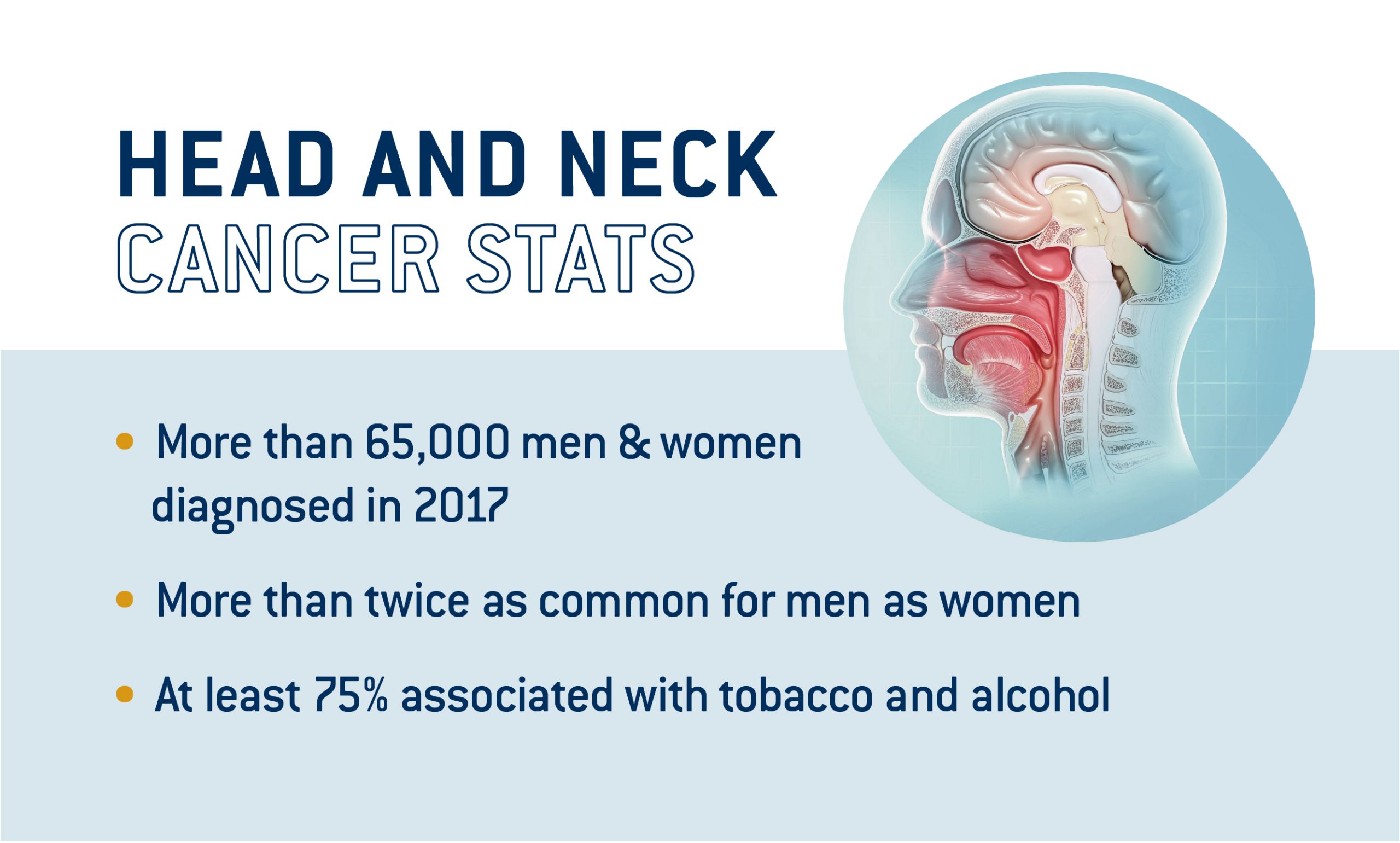

To that effect, a new head and neck cancer clinic recently opened in Emory University Hospital Midtown based on the knowledge that patients do better when clinicians can interact and collaborate.

“We didn’t design a physician-centered clinic,” says El-Deiry. “We designed a better place for patients to see physicians, not for physicians to see patients.”

When Cleveland and Adair first step foot into the new clinic, they will do so as cancer survivors getting regular follow-up checks rather than as cancer patients. Adair will come, as he often does, bearing cupcakes for the staff as a sign of his gratitude.

“I love Winship, man,” he says. “Dr. Beitler has become like a friend to me and the staff are angels on this earth.”

These days, Adair shows his gratitude by spreading the word about HPV prevention and running a nonprofit literacy-focused camp called Bound for Glory to support low-income children with learning differences. He credits Winship for it all. “I probably would have never done any of this if I hadn’t had cancer.” He not only has his life back, but is determined—like his doctors—to help the lives of others.

Pictured at right Mark El-Deiry, Jonathan Beitler, Nabil Saba.

By Dana Goldman

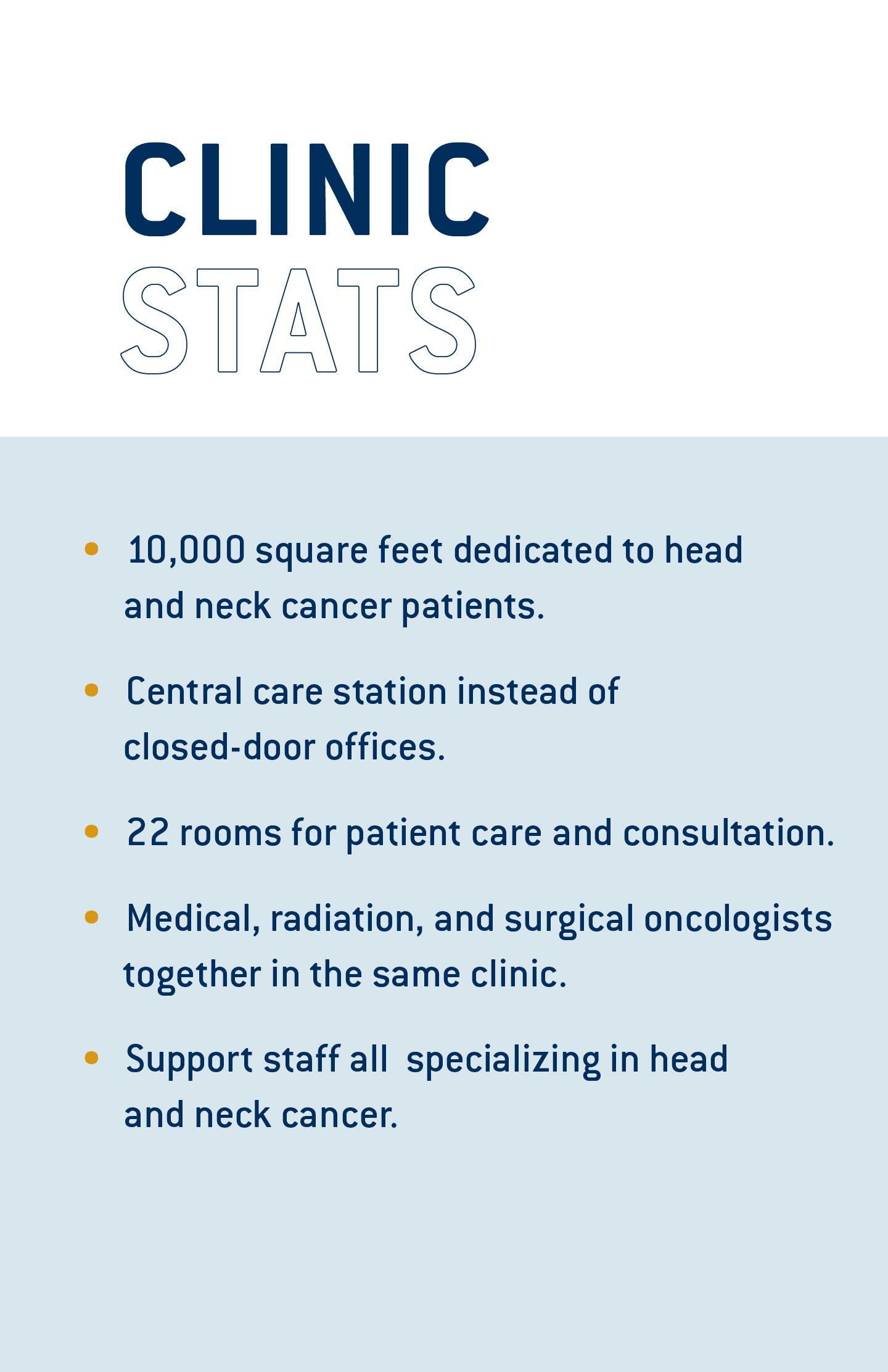

A patient-centered clinic

New 10,000-square foot head and neck clinic celebrates with ribbon-cutting

“Put the patient at the center.”

That’s been the guiding principle throughout the process of designing and building a new Head and Neck clinic on the 10th floor of Emory University Hospital Midtown, and it is now the model for how Winship is changing the way cancer patients will be treated throughout the system.

Clinic staff celebrated with an official ribbon-cutting Sept. 26, but it has been open for several months and staff say they can’t imagine going back to the old model.

Walter J. Curran Jr. (center, left), executive director of Winship Cancer Institute, and Mark El-Deiry (center, right), director of the Head and Neck Oncology Surgery Center, help cut the ribbon to celebrate the new head and neck clinic.

Walter J. Curran Jr. (center, left), executive director of Winship Cancer Institute, and Mark El-Deiry (center, right), director of the Head and Neck Oncology Surgery Center, help cut the ribbon to celebrate the new head and neck clinic.

Patients come to the one location to see all of their doctors and support staff. The clinic features a central area, known informally as “the fish bowl,” where doctors, nurses, therapists and other staff can gather to review a patient’s status. The patient doesn’t need to schedule additional appointments in other parts of the facility. It’s all centralized in the one clinic.

The innovative new 10,000-square foot clinic has 22 patient care rooms that may be used for appointments with any physician or health care provider at any time—so patients can stay put in one space and have multiple providers come to them during a single appointment.

In addition to the medical, radiation and surgical oncologists, the clinic is fully staffed with speech therapists, clinical trial researchers, advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, social workers, dietitians, nutritionists and dentistry experts, all specializing in head and neck cancer.

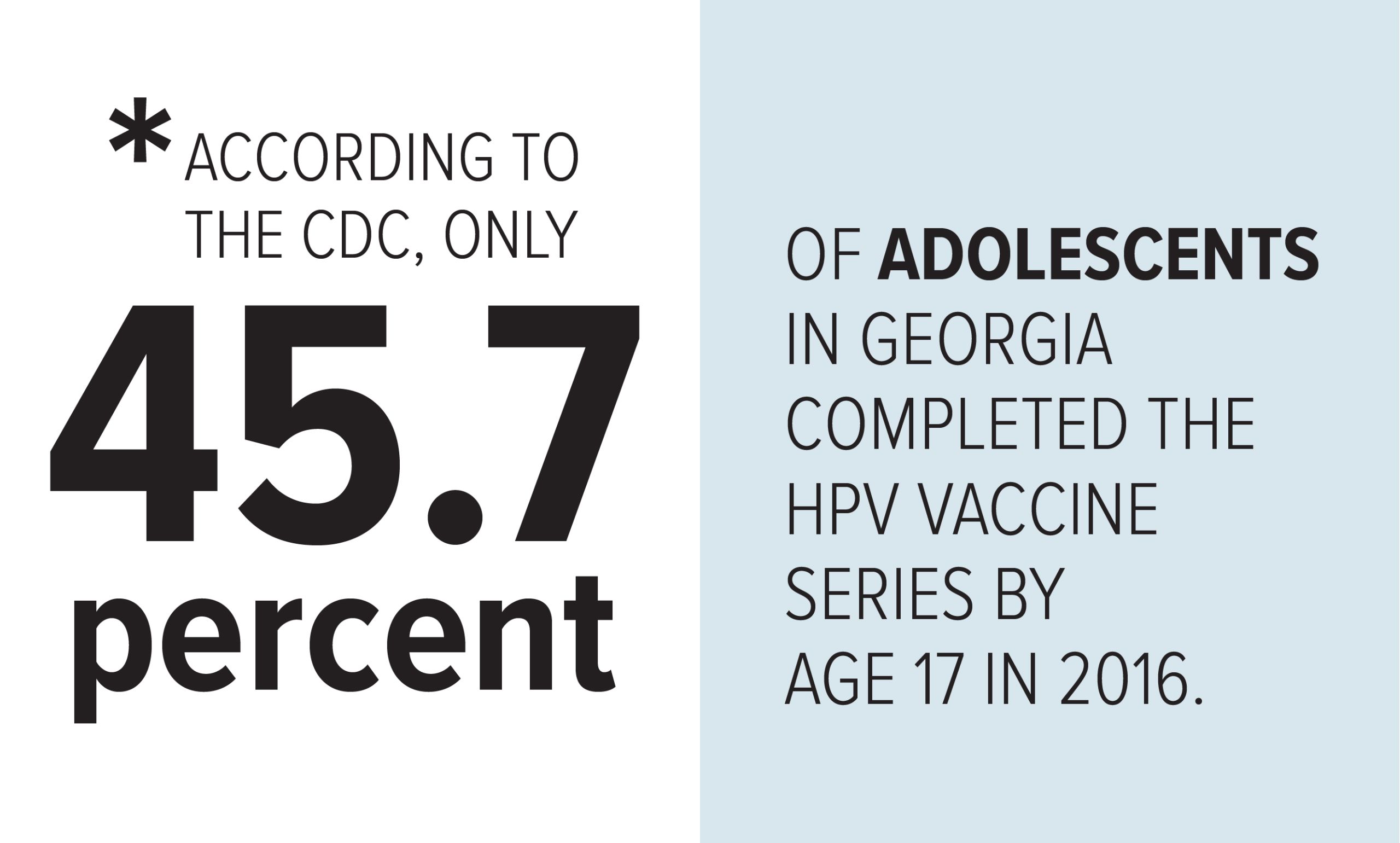

What Georgians know about HPV

Two common misperceptions about HPV (human papillomavirus): only women get cancers from HPV infection; if you don’t have symptoms of HPV infection, then you haven’t been exposed to the virus.

Adrian King, coordinator of a Winship project that researched attitudes about HPV vaccination in Georgia, heard these misconceptions and many more when he conducted 23 focus groups around the state and a survey of 700 Georgia parents of 9 to 17-year-olds.

The project, led by Robert Bednarczyk, Winship member and HPV researcher in Emory's Rollins School of Public Health, was launched in 2017 by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) that is a supplement to Winship’s NCI Cancer Center Support Grant. Working closely with regional cancer coalitions, the researchers dug deep into rural areas throughout Georgia and talked to parents, health care providers, religious and community leaders, and to the adolescents themselves, to find out what they know about HPV and what information is needed to help people understand the value of HPV vaccination.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States. It’s known to be the most common cause of cervical cancer and is now thought to be associated with 70 percent of oropharyngeal cancers (back of the throat, including the base of the tongue and tonsils), which are affecting younger people, particularly men ages 40 to 55, in greater numbers.

The HPV vaccine is most effective when given to boys and girls at ages 11 to 12, but vaccination rates are low. King, a public health program associate at Rollins, says their research showed that parents think their children are too young to be vaccinated against a sexually transmitted virus. Other findings point to a general lack of information and knowledge about vaccinations and a disconnect in communication between doctors and parents. Although health care providers reported that they “strongly recommended” the vaccine to parents, parents didn’t remember hearing that message.

Adrian King (left) and Robert Bednarczyk led a team of researchers who gathered data from throughout Georgia.

Adrian King (left) and Robert Bednarczyk led a team of researchers who gathered data from throughout Georgia.

Bednarczyk says the research highlights the importance of understanding belief systems and how people make decisions. Discussing people’s misconceptions, he says, is more effective than dismissing them: Everybody is trying to do the best for their children. We’ve discovered that it’s not just what we’re communicating, but how we’re communicating it.

King says he’s keen to take the next step and use the research and momentum of the project to develop messages and tools to communicate them. Bednarcyzk says they’re hoping for two grants to come through that will enable them to do that.