EXPERT WITNESS

Forensic nurse Trisha Sheridan testifies in classrooms and courtrooms to help victims of violence

Forensic nurses are a special breed.

They provide specialized care to victims of child abuse and neglect, domestic violence, sexual assault, human trafficking, elder abuse, and other forms of trauma and harm often experienced by vulnerable and high-risk populations.

Trisha Sheridan is one of 25 certified forensic nurses in Georgia.

Trisha Sheridan is one of 25 certified forensic nurses in Georgia.

These advanced practice nurses (APNs) may be called upon in the aftermath of mass disasters, but much of what they regularly see is the result of personal violence that too often is hidden away out of shame or fear. Forensic nurses are experts in recognizing signs of abuse, detecting and treating injuries, collecting evidence, and providing testimony to apprehend and prosecute perpetrators.

Nationally, the number of forensic nurses, especially those certified as Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs), is rising thanks to growing awareness about sexual assaults and other forms of violence and the need to expand SANE education and certification.

Unfortunately, says School of Nursing forensic expert Trisha Sheridan DNP WHNP-BC SANE-A SANE-P, the majority of Georgia’s 170 hospitals lack access to this kind of expertise. Many people in the health care and legal systems—not to mention the general public—don’t fully understand the role and value of forensic nursing.

Sheridan, one of 25 certified forensic nurses in Georgia, was recruited to Emory four years ago after Dian Dowling Evans 90MSN PhD FAAN, specialty coordinator of the Emergency Nurse Practitioner program, heard her teach an elder abuse course through the International Association of Forensic Nursing (IAFN). At the time, Sheridan had just updated the IAFN’s elder abuse guidelines.

She already knew a lot about the School of Nursing. Angela Amar PhD RN FAAN, who previously taught forensic nursing at Emory and is now dean of nursing at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, had been her mentor.

Today, as assistant professor and coordinator of Emory’s Women’s Health Nurse Practitioner program, Sheridan offers two elective forensic courses. In the course for BSN students, medical examiners and other community partners deliver guest lectures on how the health care and legal systems deal with different types of violence—and the role nurses can play within their specialties.

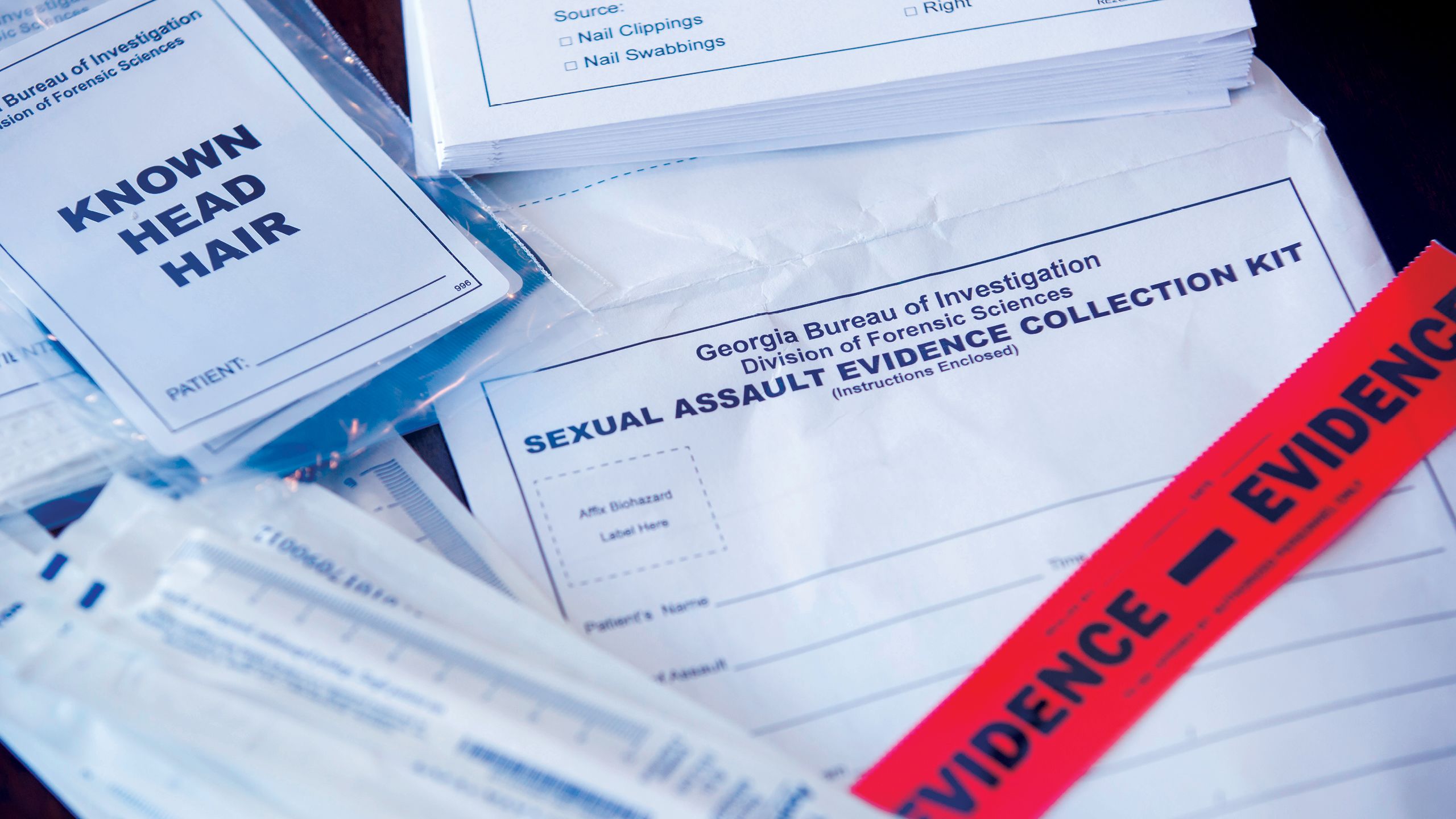

In the advanced course, MSN students learn how to perform forensic exams and collect evidence, making Emory one of the few nursing schools that offer forensics in the basic curriculum.

It’s important that providers learn to recognize signs of abuse. Victims may be unwilling to volunteer information out of embarrassment or fear. For example, young victims of human trafficking average seven encounters with the health care system before someone realizes their situation.

—Forensic nursing expert Trisha Sheridan

While Sheridan would like to encourage more students to become forensic nurses, she’s also intent on making sure that every nurse, no matter her or his specialization, is familiar with the goals, methods, and manners of forensic nursing.

“Unless a forensic specialist is on staff at a health care facility, a nurse with even limited training is likely to be best prepared to work with victims of child, sexual, elder, or other abuse and trauma,” says Sheridan.

It’s also important that providers learn to recognize signs of abuse. Victims may be unwilling to volunteer information out of embarrassment or fear. For example, young victims of human trafficking average seven encounters with the health care system before a clinician realizes their situation.

Sheridan writes and speaks to reach as many nurses as possible. She now leads a two-day clinical skills training course through the Emory Nursing Professional Development Center. The first class drew 20 registrants, and more classes are on the books.

To further widen understanding of forensic nursing, Sheridan teaches residents in Emory School of Medicine, partnering with emergency medicine physician Lauren Hudak MD. Just recently, she worked with the DeKalb County District Attorney’s office to instruct staff about child abuse medical examinations.

The experience that set Sheridan on the path to forensic nursing happened a decade ago, when she worked as an APN in a family planning clinic in greater Washington. D.C. A young woman arrived in so much pain she could barely walk. Although she had been sexually assaulted four days earlier, she did not go to the hospital until Sheridan agreed to go with her.

Once at the local emergency room, the nurse on duty grew impatient when the woman was reluctant to report the assault. Then why are you wasting our time? The physician called in to do a pelvic examination barely spoke to the woman except to ask if she ever had herpes. No? Well you do now. He handed her a prescription and left.

Sheridan asked herself: What just happened here? She soon began studying to become a forensic nurse and, three years later, a SANE nurse.

All too often, sexual assault victims believe health care providers focus solely on collecting evidence, which prevents many from seeking care. In addition to collecting evidence to aid in criminal prosecution, providers assess and treat injuries; prescribe prophylactic medication to prevent pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and HIV; and, most importantly, help victims regain a sense of autonomy and power.

That may be especially true for victims of sexual trauma. “Rape is always about exerting power, never about sex,” says Sheridan. “That’s why everything in the patient encounter—from history-taking to head-to-toe physical examination and data collection—must be done respectfully and with the patient’s consent.” May I touch you here? Do you want to apply the swab yourself?

Sheridan’s desire to better understand violence and trauma led her to pursue a doctorate of nursing practice at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center. Her dissertation focused on sexual assault, specifically on HIV prophylaxis for assault victims. But her greatest lessons come from the victims of violence she has met in clinical practice, primarily in Texas, where she was the only forensic nurse in a highly populated seven-county area. Her patients? Women, men, and transgender individuals. Children and senior citizens. People from all ethnicities, socioeconomic classes, and walks of life. Successful professionals and young men and women caught up in human trafficking.

What she learned from them has continued to shape what she teaches her students in health care and law. The right response to victims, she says, can empower them, alleviate their distress immediately after a trauma, contribute to their recovery, and positively affect long-term outcomes such as depression, shame, or suicide risk. The right response can help them resume living a normal life.

Story by Sylvia Wrobel | Photography by Stephen Nowland

Designed by Linda Dobson

The Evolution of Forensic Nursing

Although nurses had long included aspects of forensic nursing in their practice, the field first gained formal recognition by the American Nurses Association Congress on Nursing Practice in 1995. Leading the way were Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs), who sought to standardize and be recognized for their work with sexual assault victims and their families and expand and strengthen their relationships with medical examiners and legal professionals.

Today, other forensic nursing specialties include correctional nurses working in prisons and correctional facilities, forensic nurse death investigators (in some areas nurses may serve as coroners), intimate partner violence specialists, child abuse and neglect specialists, elder abuse specialists, forensic psychiatric nurses, legal nurse consultants, and clinical risk managers who deal with falls, injuries, and deaths among patients and staff in hospitals and in-patient facilities.

What these nurses have in common is education in specialized care to address the physical, psychological, and social trauma of assault or abuse and working with the legal system.

How many such nurses are there? The International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN) has more than 4,200 members—three-fourths of whom identify as SANE nurses—but its leaders believe the number is considerably higher. IAFN has certified 1,140 SANE-A nurses working with adults and adolescents and 465 SANE-P nurses working in pediatrics. Certification is not required to become a SANE or general forensic nurse, however. Nurses learn in the classroom, virtually, and through continuing education programs like the one offered by the Emory Nursing Professional Development Center. Other education sites are listed on the IAFN website (www.forensicnurses.org). Nurses must make sure their education meets the requirements of the state where they practice.

Want to know more? Please visit

Emory Nursing Magazine

Emory News Center

Emory University