COMMUNITY CONNECTIONS

Emory takes African American arts exhibit into Atlanta middle school

It’s a rainy spring evening at Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School, and the building is abuzz with Parents’ Night and the opening of “Speak What Must Be Spoken,” an Emory exhibit that’s been reimagined and reborn in this busy Atlanta public school.

Throughout the hallways, students are showing parents around the exhibit, which draws on materials from Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library. In the dance studio, large photos of choreographers Carmen de Lavallade and Geoffrey Holder, along with Alvin Ailey dancers in flight, decorate the walls. In the art studio, images of artists Benny Andrews, Romare Bearden, and Samella Lewis enliven the room.

The spark for this school-based initiative came from Emory Libraries’ “Still Raising Hell: The Art, Activism, and Archives of Camille Billops and James V. Hatch.” Held in Woodruff Library’s Schatten Gallery during the 2016-2017 academic year, that major exhibition showcased the collection of Billops and Hatch, a New York couple who have spent more than 40 years creating and collecting African American art and art history and documenting the work of other writers, dancers, and artists.

During its run, the exhibition asked viewers to consider how art in all its various forms, and particularly black art, could effect change. Brainstorming about how to extend the library’s K-12 outreach, organizers created “Speak What Must Be Spoken,” a traveling exhibit that pulled materials from Billops-Hatch and other collections and posed that question to students.

Now, images of African American artists and icons, many of whom were previously unknown to these King Middle School students, adorn the walls of their daily environment.

From the beginning, though, project organizers knew they wanted to do more than hang images in hallways: they wanted the items on view to create a lasting impact. That meant working with educators to incorporate art and activism into the curriculum and to weave those themes into lesson plans. And tonight, those lessons have come to life.

Students perform a dance routine inspired by the "Speak What Must Be Spoken" exhibit.

Students perform a dance routine inspired by the "Speak What Must Be Spoken" exhibit.

Audience members watch in amazement as students stage a performance of dance, music, poetry and acting in an original skit that encourages them to believe in themselves, pursue their dreams, speak their truth and stand up against injustice.

Between parts of the skit, students dance to recordings of Maya Angelou reading her poem “Still I Rise,” Alicia Keys singing “Girl on Fire,” Andra Day singing “Rise Up,” and Malala Yousafzai reading her 2014 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech.

“I was so impressed by the outcome,” says Emory University Librarian Yolanda Cooper. “They were able to develop a creative, thought-provoking program around the exhibit that I didn’t expect. We had two specialists develop curriculum related to the exhibition, but what I saw was more than curriculum. It was an artistic transformation that came out of the materials themselves.”

Emory in community schools

Seeing these middle school students apply their newfound knowledge of black art and activism to create new works left everyone involved in the project feeling uplifted.

“We hope that the images installed at the school will be meaningful to the kids,” says Pellom McDaniels III, Rose Library curator of African American collections, who curated both the original Billops-Hatch exhibition and this school-based exhibit. “They can see people who look like them and have had great careers in the arts, which will allow them to think about their own potential opportunities.”

As its first traveling exhibit into the Atlanta Public Schools, or any community schools, “Speak What Must Be Spoken” is a milestone for Emory Libraries and Information Technology Services (LITS). It reflects the Rose Library’s commitment to bring its archives out into the community and responds to the university’s strategic framework, which calls for deeper engagement with the Atlanta community.

“One of our goals is to create more points of access to the unique and rare materials in the Rose Library for the larger Atlanta community,” McDaniels says. “It’s one thing for us to make research materials available for our students and faculty and outside researchers. It’s another thing to interpret documents, photographs, and ephemera in ways that inform a public that’s hungry for these kinds of experiences.”

Launching pad for future projects

Cooper believed in the project from the start and was willing to invest in it with library reserve funds. “I liked the idea. I thought it was something we needed to do, to move more into community involvement,” she says. “We’ve had conversations about K-12, especially with the Rose Library, and how to make deeper connections with the broader community, so this would give us an opportunity to develop a concept model and see how we could fund it for the long term.”

The project team consisted of McDaniels; LITS exhibitions manager Kathy Dixson and her team members Caroline Corbitt and John Klingler; Emory Graduation Generation Education Partnerships manager Barbara Coble; LITS Campus & Community Relations director Leslie Wingate; and King Middle School curriculum specialist Johnnie Ford.

Wingate describes the project as one of the most meaningful of her 15-year Emory career. “Getting to work with such a talented team and doing work that is so impactful to both children and adults was deeply enriching for me,” she says. “And the connection we forged with Johnnie Ford and King Middle School will serve as a launching pad for us to deepen relations between Emory Libraries and the Atlanta K-12 community even more.”

The team brought Coble on board, who has fostered many Emory partnerships with area schools over the years. She created the curriculum around the exhibit materials with the help of Emory student interns and collaborated with Ford, who worked with the middle school teachers and students.

“We hope that the images installed at the school will be meaningful to the kids,” says Pellom McDaniels III, Rose Library curator of African American collections, who curated both the original Billops-Hatch exhibition and this school-based exhibit. “They can see people who look like them and have had great careers in the arts, which will allow them to think about their own potential opportunities.”

A year of art and activism

The “Speak What Must Be Spoken” lesson plans began with the fall 2018 classes, and as the students became immersed in their work, they explored an online version of the Billops-Hatch exhibit, answered related questions, and studied black artists from the 1960s and their activism.

Last October, the library exhibitions team began installing materials throughout the school, including filling its dance and art studios with photos from the Billops-Hatch collection. Those images will stay on after the rest of the exhibit comes down, McDaniels said, to serve as lasting role models to classes there.

In another part of the school, along the hallway that leads to the lunchroom, Atlanta-based artist Keef Cross’s portrait series, “A Change is Gonna Come,” lines the orange walls. The series, which also appeared in the previous exhibition, includes James Baldwin, Aretha Franklin, Maya Angelou and other black artists and activists. On the day he visited an art class, Cross talked about the path he followed and answered questions from students, and Coble developed a lesson around the people featured in his series.

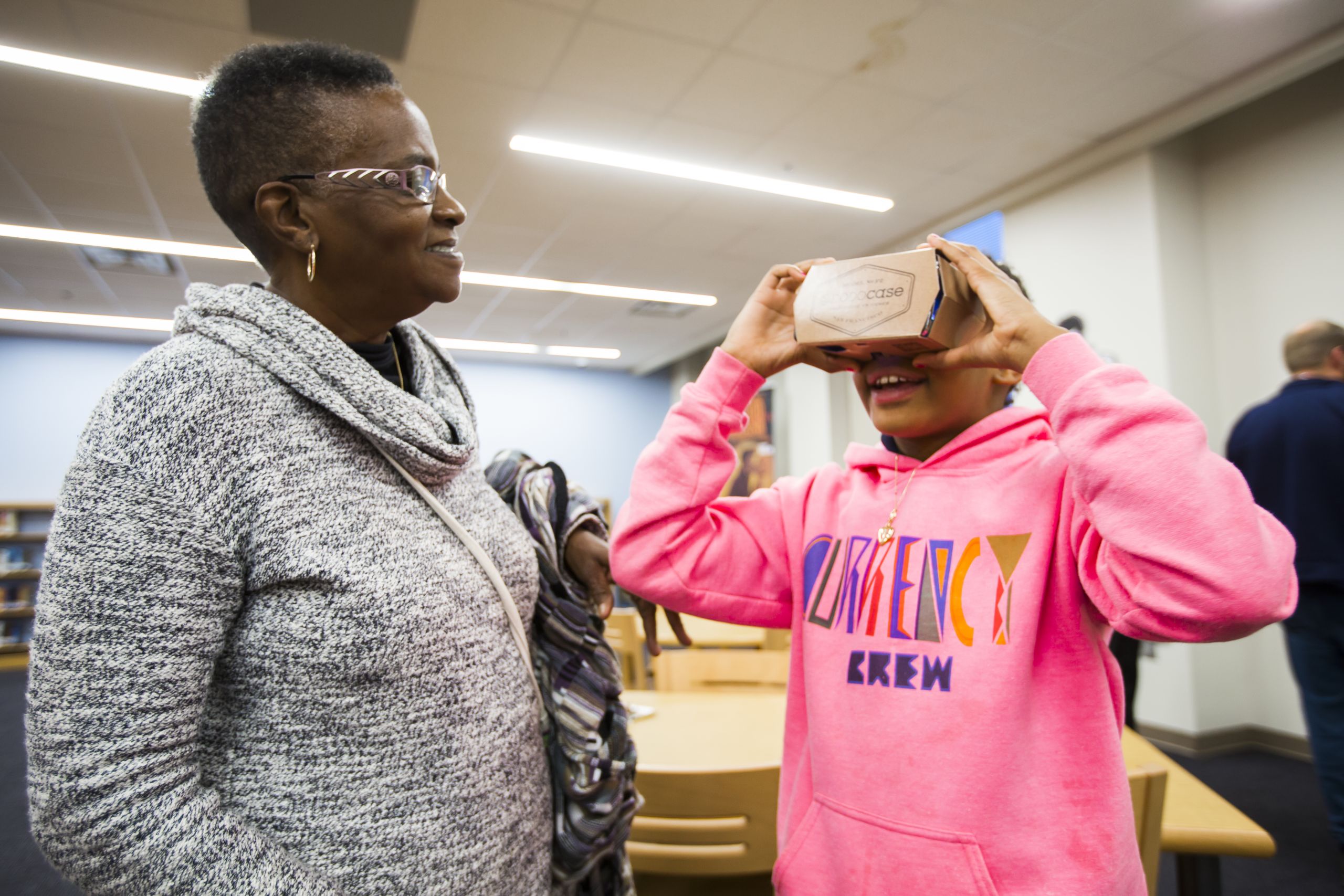

Elsewhere in the building, panels depicting the streets of the Brotherman/Big City Maps project, created by Emory’s Center for Digital Scholarship, brighten the school’s media center. Students can virtually enter the imaginary streets of Big City with 3-D viewfinders that remain with that exhibit section.

Dawud Anyabwile (seated, with tablet), illustrator and co-creator of the “Brotherman” superhero comic book, shows the printed comic book and the digital project to students and their families.

Dawud Anyabwile (seated, with tablet), illustrator and co-creator of the “Brotherman” superhero comic book, shows the printed comic book and the digital project to students and their families.

Dawud Anyabwile, illustrator and co-creator of the “Brotherman” superhero comic book, spoke to the students and parents during the opening performance about his career journey with the Brotherman series. He told them how the lack of positive African American role models in comic books led him to create his own lead character, an everyman who engages in heroic deeds at night in his town, Big City.

The impact for Atlanta students

After the opening night performances, the students dispersed to various sections of the exhibit to introduce parents and guests to the materials and activities. Sixth-grader S’Yona Kelly demonstrated how to make origami butterflies near section titled “A Veneration of Ancestors.” This exhibit area features student-made origami butterflies and enlarged slides from the 1960s on a banner that depicts Billops and Hatch with artists and friends who have since passed away.

Kelly says the slides are her favorite part of the exhibit.

“It reminds us that we’ve lost a lot of loved ones and shows that they’re still in our minds and we haven’t forgotten them,” she says. “And it makes me feel inspired.” She has started taking photographs, she adds, and recently got her own camera and tripod. “I’m a beginner. I just started in January,” she says.

For sixth-grader Legend Jones, his favorite part of the exhibit was the Brotherman section with Big City’s 3-D maps, where he could zoom in to the street level and take a look around. But Anyabwile’s story of how he started on his path, particularly how he created the first black superhero in the indie comics world, will also stay with Jones.

“I think it’s cool that before he got started, there weren’t really any black superheroes in comics,” Jones says. “I’m not good at drawing, but he told me that’s okay, as long as you keep trying.”

The future of traveling exhibits

Even before the exhibit closes in June, plans are under way for a version of it and its accompanying curriculum to move to another, to-be-determined Atlanta school this fall.

“We have very deep collections that a lot of these kids may not ever have a chance to see,” Cooper says. “It’s important for the university to have this kind of connection with the community. The university, through its strategic plan, supports new outreach activities like these traveling exhibitions.”

For now, Ford says it’s a thrill to witness the material making an impression on the students.

“You see them lingering in the halls sometimes near one of these exhibit panels on the wall, and you want to tell them out of habit to keep moving,” she says. “But then you see that they’re reading the exhibit panel so intently, and you can see on their face that something is happening, and they’re making a connection. That’s so exciting. You just let them be when that happens.”

ABOUT THIS STORY: Written by Maureen McGavin. Photos by Kay Hinton.

To learn more, please visit

Emory University, the Emory News Center and Emory Libraries.