Restoring vision

and hope to refugees

Emory Eye Center physicians are making a difference to Syrian refugees in Jordan

In the summer of 2016, when Emory Eye Center cornea specialist Soroosh Behshad, MD, MPH, kept seeing news stories and social media posts about the hardships and trials of Syrian refugees (particularly children), he knew he wanted to use his career as an ophthalmologist to effect a positive change not only in his own community, but internationally as well. Although the Emory faculty member had no connection to Syria, he has always been interested in refugee health care.

“Unfortunately, the situation within Syria is too dangerous to travel there, so my initial involvement was based on using technology to make an impact,” he says. By August 2016, he began offering tele-ophthalmology consultations to first responders in Syria and consultation for management of difficult cases (specifically ocular trauma) to hospitals in the Syrian conflict zone.

He continued to work with non-governmental organizations who were providing care to Syrian refugees residing in neighboring countries and then began collaborating with the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) to set up ophthalmological care for Syrian refugees living in refugee camps in Jordan. Since January 2017, he has traveled every few months to Jordan to provide surgical and clinical eye care for refugees.

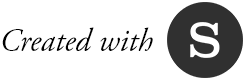

Initially, he started by providing cataract surgery, eye injections, laser procedures, and giving out glasses. After the first trip, Behshad noticed a large incidence of amblyopia (sometimes known as “lazy eye”) in the children. Untreated amblyopia in children can lead to irreversible blindness. Normally, the condition is diagnosed during routine vision screenings in school. Most of the refugee children were not in school because they worked to help support their families, so the blindness caused by amblyopia was being missed.

Behshad then collaborated with Emory Eye Center pediatric ophthalmologist Natalie Weil, MD, to establish a program to screen and treat pediatric amblyopia in the refugee camps. They work directly with local ophthalmologists, residents, and medical students to provide the services.

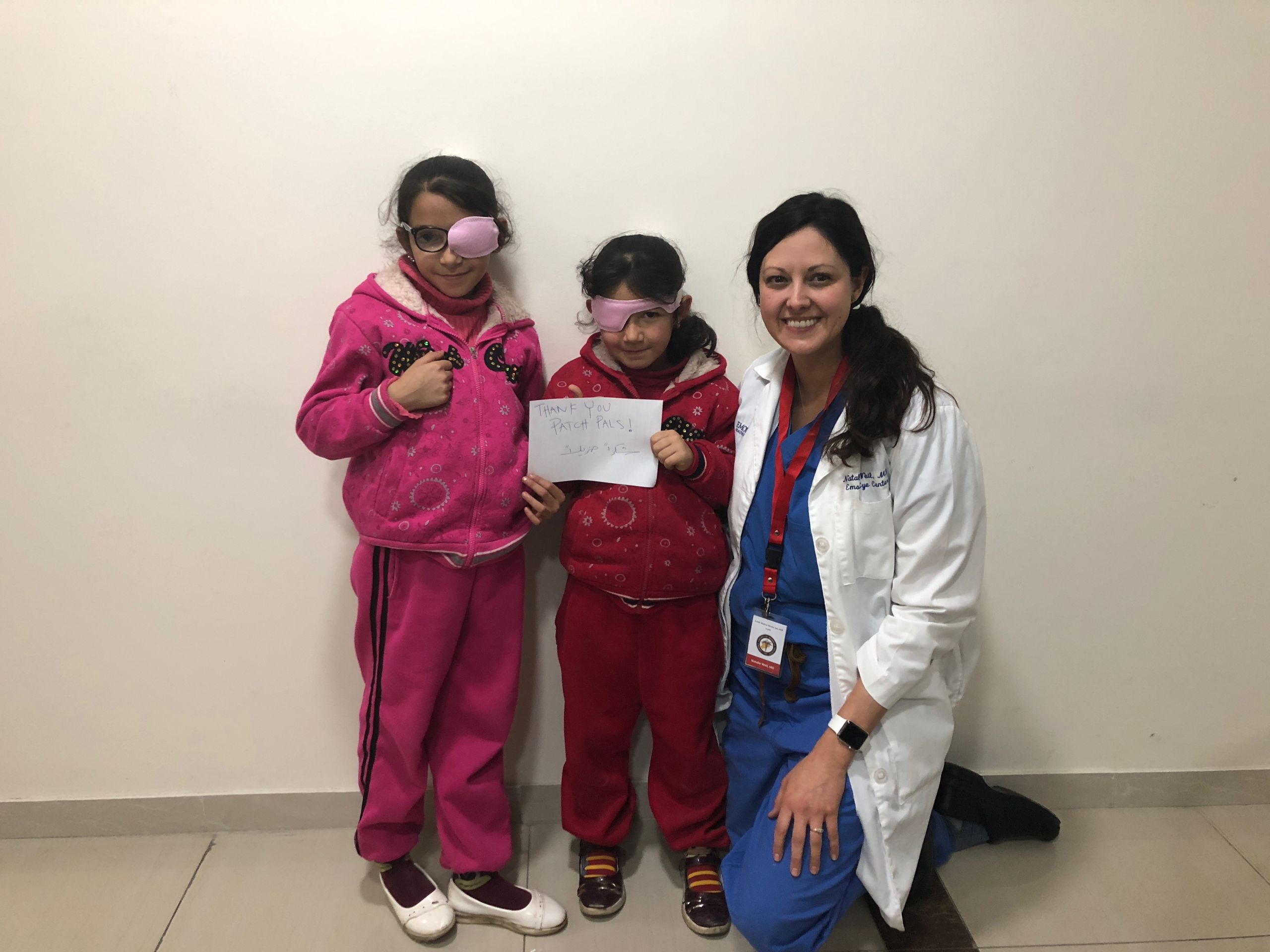

“Working in conjunction with pediatricians allows us to reach more patients,” Weil says. “After identifying patients who failed a vision screening, we complete a full eye exam and provide patients with the appropriate glasses or patching, if needed. We’ve been fortunate to work with Patch Pals, a group that has donated reusable cloth patches for all the refugee children who need amblyopia therapy.”

Vision screenings also have identified patients with inherited retinal dystrophies, juvenile cataracts, active ophthalmic infections, congenital eye-related conditions, and strabismus.

Ophthalmologist Soroosh Behshad first traveled to Za'atari to treat Syrian refugees in January 2017. He returns every few months to provide eye care.

Ophthalmologist Soroosh Behshad first traveled to Za'atari to treat Syrian refugees in January 2017. He returns every few months to provide eye care.

Dr. Behshad performs cataract surgery and other procedures during his trips to Za'atari. He also teaches Syrian doctors so they are better prepared to diagnose and treat patients themselves.

Dr. Behshad performs cataract surgery and other procedures during his trips to Za'atari. He also teaches Syrian doctors so they are better prepared to diagnose and treat patients themselves.

"I've learned to travel light," Dr. Weil says of treating the refugees. "I can basically fit everything I need for a pediatric eye exam in a backpack."

"I've learned to travel light," Dr. Weil says of treating the refugees. "I can basically fit everything I need for a pediatric eye exam in a backpack."

Children are seen everywhere in Za'atari, from young ones playing among the metal shelters to older ones helping support their families.

Children are seen everywhere in Za'atari, from young ones playing among the metal shelters to older ones helping support their families.

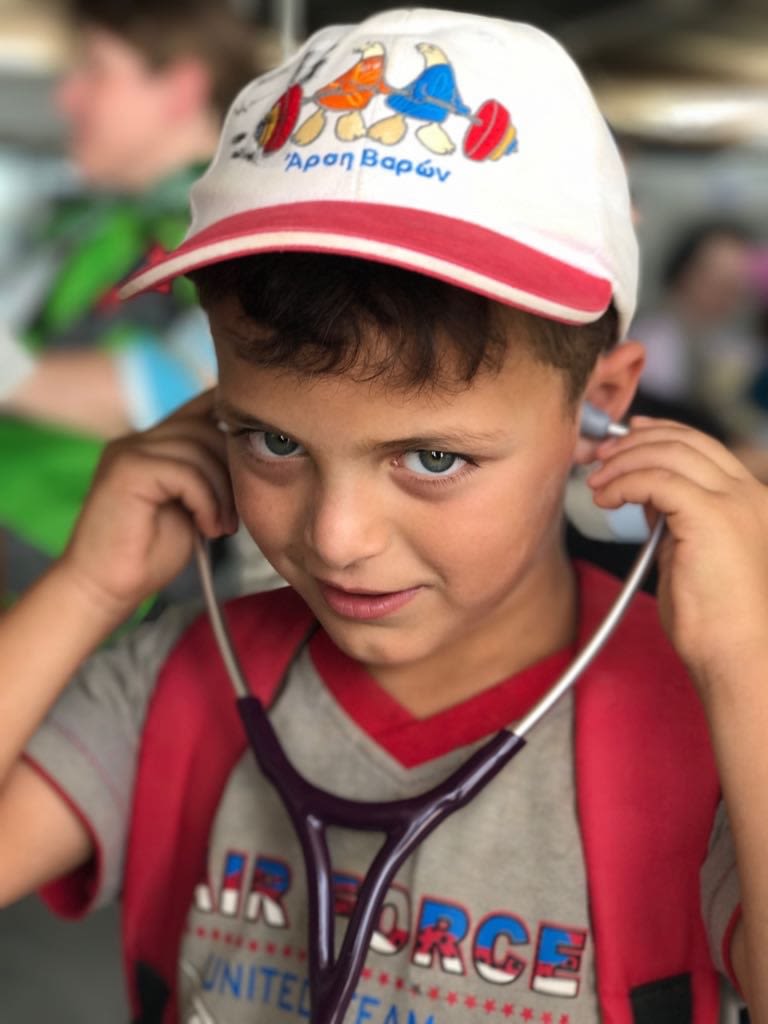

In addition to treating patients, Behshad and Weil use their visits to educate Syrian providers. In January 2018 they were able to bring three of the four remaining ophthalmologists out of the Syrian war zone for further education and training.

“The time we're able to spend in clinic is regulated by guards,” Dr. Behshad says. “They say when we can go in and when we must leave. We never know exactly how long they'll allow us to be there each day. We see as many patients as possible during whatever time we have.”

Dr. Weil works with Patch Pals to provide refugee children with the eye patches they may need after surgery or to help treat amblyopia or strabismus.

Dr. Weil works with Patch Pals to provide refugee children with the eye patches they may need after surgery or to help treat amblyopia or strabismus.

Dr. Weil reassures one of her pediatric patients (and his grandfather) before surgery to treat a congenital nerve palsy.

Dr. Weil reassures one of her pediatric patients (and his grandfather) before surgery to treat a congenital nerve palsy.

Success! Dr. Weil celebrates with a patient following a vision exam. "They are all so grateful for any care we can give them," she says.

Success! Dr. Weil celebrates with a patient following a vision exam. "They are all so grateful for any care we can give them," Dr. Weil says.

Many adult refugees that Dr. Behshad and Dr. Weil treat have experienced years of vision loss due to cataracts. Most are all smiles after their surgery.

Many adult refugees that Dr. Behshad and Dr. Weil treat have experienced years of vision loss due to cataracts. Most are all smiles after their surgery.

The numbers of people needing care are staggering. Za’atari, the largest Syrian refugee camp, is home to more than 80,000 refugees, more than half of whom are children. The camp stretches over three square miles of desert and qualifies as the fourth largest city in Jordan. It is gradually evolving into a permanent settlement, with residents moving from living in tents to shelters made from corrugated metal containers.

Behshad and Weil have traveled to Za’atari several times and have provided eye exams or surgery for almost 10% of refugees in the camp. While there, they work closely with other international nonprofit groups, including Doctors Without Borders/Medecins Sans Frontieres and UNHCR (the U.N. Refugee Agency), who refer patients to the EMORY/SAMS team for surgical care. The Emory team established a network of local doctors to ensure all patients are followed by an ophthalmologist after their surgeries.

When in Jordan, Behshad and Weil see hundreds of patients each day over a week-long period and perform 20 to 30 eye surgeries per day. Their biggest reward comes from seeing what a life-changing difference care can make for some patients.

Weil recalls, “During my first trip I met a young girl named Bushra, who had developed dense white cataracts in both eyes and had very little vision. She was also non-verbal and unable to walk by herself. After much discussion with her family, we decided to remove the cataracts in hopes that she would gain some vision. Giving her family some small amount of hope brought her mother to tears, and touched all of us in the room.”

Behshad tells the story of Hajjeh, a mother displaced by the Syrian war who relocated to Za’atari to keep her family safe.

“She was permanently blind in her right eye due to complications from cataract surgery performed before the war,” he says. “She was fearful from this experience so had avoided surgery to correct the cataract in her left eye. The cataract had progressed to the point that she was legally blind in that left eye as well. She was dependent on a cane and her family to navigate around her tent and was unable to perform basic daily activities without assistance. She reluctantly agreed to proceed with the cataract surgery. Her vision was restored to 20/20 in that eye and for the first time in years she was able to walk independently. Her smile and happiness were contagious.”

Vision screenings have led to the diagnosis and treatment of conditions ranging from nearsightedness to inherited retinal dystrophies.

Vision screenings have led to the diagnosis and treatment of conditions ranging from nearsightedness to inherited retinal dystrophies.

Examples such as Bushra and Hajjeh compel Behshad and Weil to continue working for—and with—the refugees.

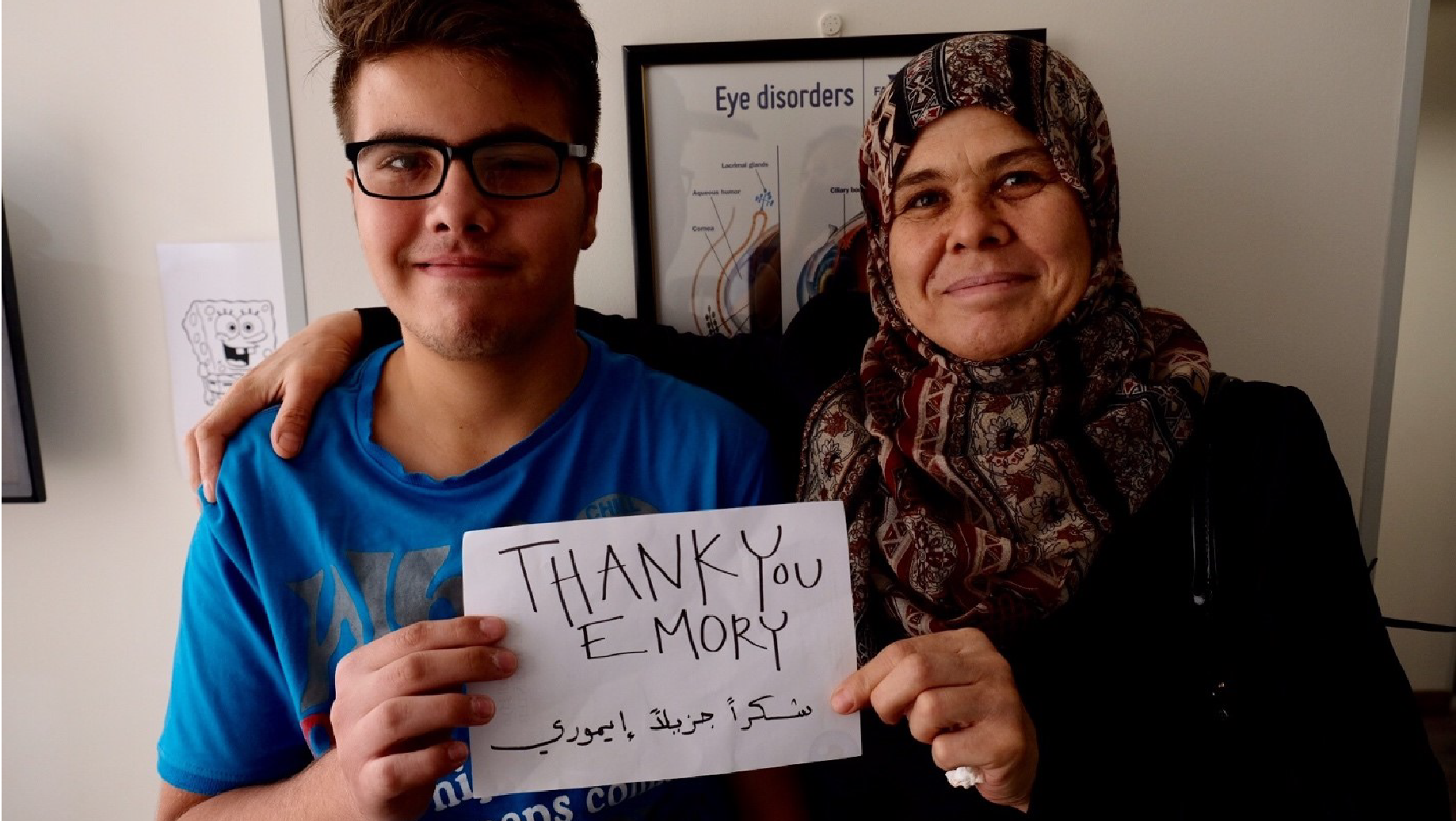

“Many patients walk into the clinic dependent on their family members to help them navigate due to their poor vision,” Behshad says. “The day after surgery they’re able to get around safely because their vision is restored. That, and the huge smiles on their faces when they learn we’ve traveled all the way from America to treat them, is priceless.”

By Leigh DeLozier | Photos by Soroosh Behshad, MD, MPH, and Natalie Weil, MD

Za’atari Refugee Camp

Za’atari covers three square miles of Jordanian desert. With more than 80,000 Syrian refugees living there, the camp qualifies as the fourth largest city in Jordan.

Home away from home

More than half of the people living in Za’atari are children. Many of them were born in the camp or are too young to remember their homes in Syria.

A vision for tomorrow

“The children living at Za’atari will be the ones to rebuild their nation someday,” Dr. Behshad says. “Until then, we hope to continue working with—and for—the refugees.”

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Eye Center, Emory Healthcare, Emory News Center, and Emory University.