Journey Toward Justice

Confronting America's legacy of slavery and lynching prepares students to lead communities on the road to racial reconciliation

Story by Kimber Williams | Photography by Stephen Nowland

Emory University | Dec. 14, 2018

The journey begins quietly, in muted contemplation of what lies ahead.

By 6:30 a.m. on a sleepy Saturday morning, more than 150 students, faculty, staff and alumni have assembled at Emory’s Candler School of Theology awaiting a fleet of four tour buses, which glide into place just outside, clouds of exhaust billowing ghostly shadows in the chilly pre-dawn air.

Conversation is warm but subdued, hardly the lively, laughter-filled chatter of a typical student field trip. And that’s understandable.

Because from its inception, this outing — entitled “Journey Toward Racial Justice and Healing” — was intended to offer something very different, part of a school-wide initiative deliberately designed to encourage the Candler community to engage in — rather than retreat from — difficult conversations.

Over the past three years, that has included a push to grapple with topics of difference, racial healing and social justice, the very kinds of challenges these budding theologians will encounter in their future leadership roles within churches, communities and universities.

And this trip promises to nurture tough conversation, focused on confronting America’s long, painful history with slavery, racial violence and lynching.

That’s how this diverse contingent came to embark on a 160-mile journey last month from Atlanta, Georgia, to Montgomery, Alabama — to better understand how our shared past has shaped the very foundation of today’s cultural landscape.

Destinations include the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum, which traces America’s legacy of slavery, racial terror, segregation and mass incarceration, and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the nation’s first memorial dedicated to enslaved black people and the horrors of lynching.

But for the Candler community, the trip is part of a much larger journey, the embodiment of longstanding institutional commitments to shape leaders dedicated to ministries of “justice, righteousness, peace and the flourishing of all creation.” For generations, the school’s core values have been deeply rooted in diversity and social justice.

This spiritual pilgrimage is one more chapter in that story, notes Jan Love, Candler’s Mary Lee Hardin Willard Dean, responsive to both the school’s growing racial diversity — this year’s student body is 31 percent African American — and a bitterly divided national climate, especially concerning topics of race and justice.

The goal is simple: to deepen an understanding about the region’s complicated history of race relations, particularly the roles Christians have played within that history. Doing so, she believes, will help nurture more authentic conversations, preparing students to better serve diverse communities.

For Love, that matters. She grew up in Montgomery, the daughter of 1950s-era civil rights workers; her Methodist minister father fiercely supported desegregation. Racial justice was “an ever-present conversation in our household.”

Facing hard truths about a past that continues to shape the present isn’t an in-the-moment novelty, she insists. It’s a necessity.

Before boarding the buses, the travelers join in a prayer for safety and unity, strength and understanding. Crowding together, heads bow in a moment of earnest communion.

For some, the day will reveal an ugly, relatively unexplored chapter of American history — one they know little about. For others, it illuminates a past that is painful, personal and far too close.

No one who signed up for this journey is under the illusion it will be easy.

Not given the powerful impact of what awaits them — disquieting words and images that will provoke an unsettling tangle of emotions.

But they are willing to try.

Race and redemption

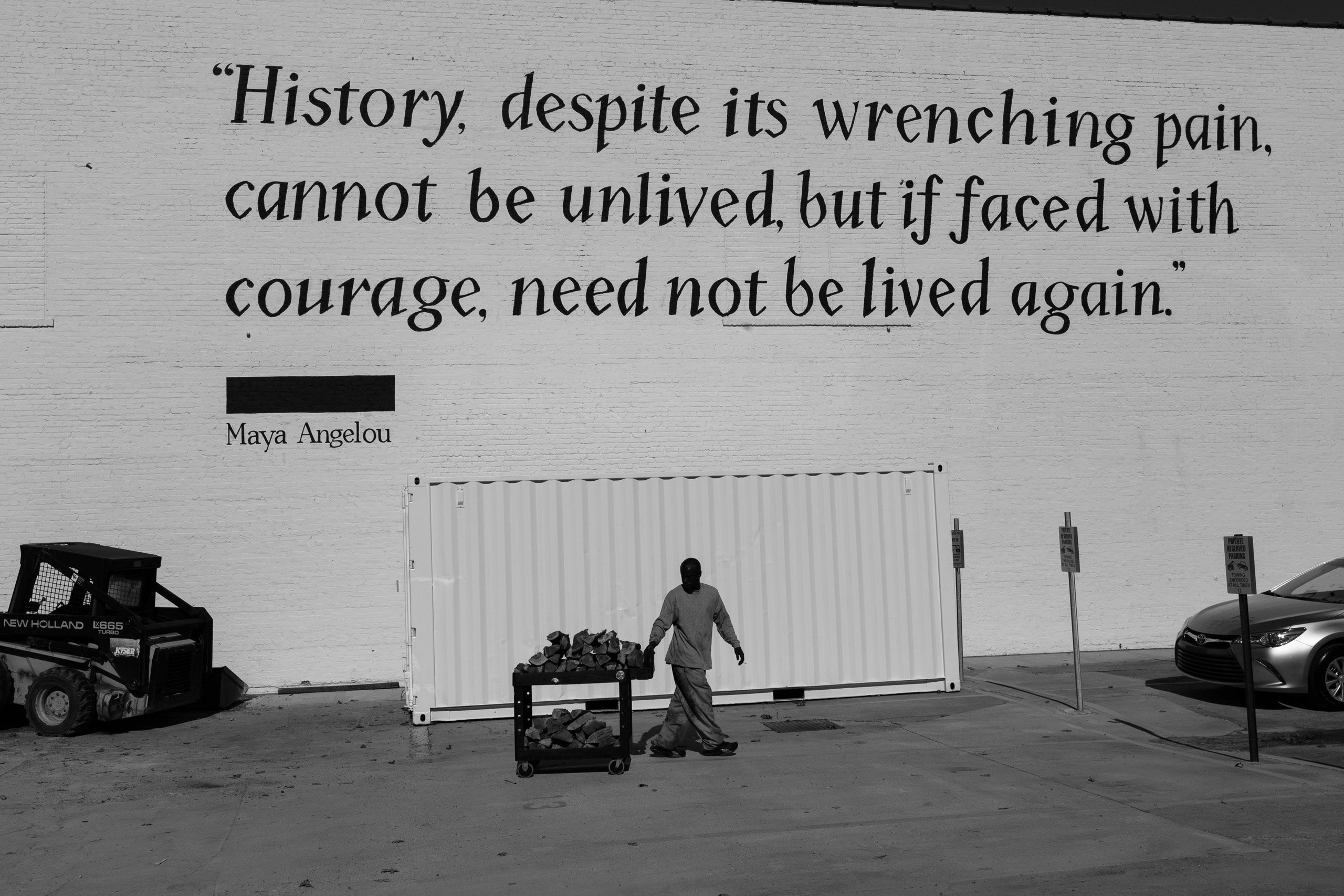

Creating a museum and memorial in the Deep South that focuses on the history of enslavement and the lynching of black people was both a deliberate and defiant choice.

For years, Montgomery was a pivotal Southern hub for the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Census records show that by 1860, a staggering two-thirds of residents here were enslaved black people — at the time, one of the largest populations of enslaved people in America.

Located in a brick storefront just off a busy downtown thoroughfare, the Legacy Museum was once the site of human holding pens.

At the epicenter of what was then the city’s robust slave market, it sits about halfway between the Alabama River, where tens of thousands enslaved men, women and children arrived in ships and trains during the 19th century, and nearby Court Square Fountain, where they were publicly auctioned off alongside livestock.

Rolling toward Montgomery through a patchy morning haze, Julian Reid reflects on the city’s complicated past. This town, he notes, was actually the first capital of the early Confederacy before it was later moved to Richmond, Virginia.

“The birthplace of civil rights and the Confederacy,” he muses, shaking his head. “It’s profound. A paradox of destruction and preservation.”

A third-year master of divinity student, this will mark his second visit to the museum and memorial, which opened in April. This summer, he visited with his wife, Carmen Reid, a student at the Emory University School of Medicine.

It’s the kind of opportunity that drew him to Emory. Growing up in Chicago, Reid was intrigued by the chance to live and work in Atlanta, a hub of Christian life in the American South with a rich history of black churches.

Working as a prison chaplain for Atlanta’s Metro Regional Youth Detention Centers while at Candler plunged him deeply into issues of economic and educational barriers, vulnerability and healing. To Reid, the trip offers “an important touchpoint for my thinking on redemption.”

“Putting the issues of slavery and lynching in your face helps you think about what this country has long sought to protect — the ability of those who are white to maintain economic, religious and social power,” he explains. “Too often, they’ve used race to get there.”

Sculptures of enslaved people at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice depict what was endured by those in captivity.

Sculptures of enslaved people at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice depict what was endured by those in captivity.

For others, the experience will be new. Carol Tucker-Burden is a part-time student and a full-time Emory employee, working as a lab manager in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory’s Winship Cancer Institute. In her spare time, she’s pursuing a master’s degree in religious leadership.

Serving an internship in her home church, Tucker-Burden wants to understand what it takes to evangelize beyond the sanctuary. She sees facilitating hard conversations a part of that.

“We have to bother to have the difficult conversations,” she says. “Stepping into issues at a critical level, instead of just circling the block.”

That’s a dedicated focus at Candler, which seeks to shape public theologians who can respond to the challenges facing increasingly diverse churches and their communities, says Love.

The need for those skills is driving demographic changes within America’s seminaries, where the number of racial and ethnic minority students has grown dramatically over the last 20 years, says the Rev. Brian Blount, board president of the Association of Theological Schools, who earned his PhD in New Testament Studies from Emory in 1992. Candler has responded by doubling down on its mission.

“Our deep theological commitments require us to work for positive transformation of the world we live in — to make it a more just and peaceful place. That is foundational — we can’t stay inside the walls of a church; we need to be outside in the world."

And it’s one of the commitments driving this trip, adds Love. “I’ve been involved in social justice work all of my life,” she says. “But after Candler students led an incredibly moving ‘die-in’ in December 2014 to protest police brutality against persons of color, it became evident to me that I needed to start a school-wide conversation on race. We need to equip leaders to proactively engage questions of race and systemic racism.”

Since then, Candler has hosted several on-campus opportunities to dialogue on race, including conversations exploring racial realities and day-long workshops on racial healing and justice, both led by guest facilitators.

And this year, the entire incoming class took part in “Fearless Dialogues,” a program developed by Gregory Ellison II that helps unlikely partners engage in difficult conversations aimed at creating change and positive transformation.

Ellison, an Emory grad and associate professor of pastoral care and counseling at Candler, led a half-day “Fearless Dialogues” workshop during orientation, and has continued the work during monthly sessions with student advising groups.

The trip to Montgomery is yet another opportunity — a particularly powerful opportunity — to proactively engage race, Love notes.

“Today is all about experiential learning — making a choice to decide that you want to know more, that you want to understand instead of skirting the issue,” she says.

Searching for empathy and courage

From a distance, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice resembles a stark, rusty Parthenon, its 800 steel pillars rising to create an open-air pavilion.

Once inside, it becomes apparent that the oxidized columns are actually monuments, each representing a county where a racially-motivated lynching took place. The names of 4,000 victims are engraved on corresponding columns. Some lists stretch the length of the pillar.

Upon entering, the columns extend floor to ceiling. But turn a corner and the floor begins to angle downward, pillars rising off the ground until eventually they dangle overhead like the lifeless bodies they commemorate. A wall of falling water honors those victims whose names are lost to history.

The mood is understandably somber, as Candler visitors pause to study a name, a location, an event. Many acknowledge they are seeking connection. A county they once lived in or visited. A name they might know. A lynching in DeKalb County, Georgia? In 1945?

The excuses behind them are unfathomable. Organizing black voters. Drinking from a neighbor’s well. Refusing to let a white man win a card game. Making a white woman feel uncomfortable. Striking to protest low wages. Addressing a police officer without saying “mister.” Scolding children for throwing rocks. Attempting to vote...

For Robert M. Franklin Jr., James T. and Berta R. Laney Professor in Moral Leadership at Candler, a connection arose unexpectedly. While visiting the memorial with his wife a few months ago, the couple found themselves thinking about where their own families had originated: Mississippi and Texas.

Locating a pillar for his home county, Franklin didn’t recognize any names. But searching for Washington County, Texas, his wife paused on the name "James Rogers."

Rogers was her mother’s maiden name.

She immediately called her mother, Gladys Goffney, an 86-year-old retired attorney now living in Houston. Rogers? Oh yes, she knew of Jimmy Rogers. He was, after all, her cousin.

Not only did she remember the heartwrenching news of his lynching, she vividly recalled the dramatic week that it happened.

It was the summer of 1944, and 12-year-old Goffney had been sent to Washington County to spend time with relatives and “get religion” — a family rite of passage. By day, she and her sister did farm chores. At night, they attended religious services.

After all these years, Goffney could still remember the men on tall horses who’d stopped to ask where she and her friends were going as they walked through the woods to attend the country church. Evening services began Sunday night and ran through the week. For four nights, she heard the distant baying of tracking hounds leading the hunt for Rogers, a young black man who’d allegedly befriended a white woman who was rumored to be pregnant.

On Thursday night, floating over the swell of church hymns, she heard their yelps accelerate with heightened urgency, then stop. She knew they had found Rogers.

More than 70 years later, Goffney could recall the ominous weight of that silence. Rogers was lynched; months later, they would learn the woman he’d befriended was never pregnant at all.

For Franklin, it was an abrupt reminder that history is not always distant. Hearing the story, he recalls “an immediate deepening and personalization of the anguish I was already feeling.”

But he knew the experience could offer an important catalyst for conversations back in the classroom: How does a loving God allow this kind of suffering? How could people who identified themselves as Christians participate? Some lynchings took place on church grounds, complete with picnic baskets and children dressed in their Sunday best. What role did the church play?

“What we’ve seen today prompts an inner search for empathy and for courage,” says Franklin, a co-leader on this trip. “Part of the courage is asking ‘What would I have done then, observing this, being aware of the violence and horror?’ And then, ‘What am I prepared to do now?’”

“I come from the descendants of slaves here in America and Jamaica. When I think about how they struggled, pushing forward and refusing to let their spirits be subdued, it leaves me beyond words…”

Julian Reid

Third-year student, Master of Divinity

“The memorial re-imagines a public square, where the ghosts of history are there looking back at you, judging you. What are you going to do with your own life once you feel those eyes upon you?”

Jennifer Arnold

Third-year student, Master of Divinity

“What we’ve seen prompts an inner search for empathy and for courage. Part of the courage is asking ‘What would I have done then, observing this, being aware of the violence and horror?’ And then, ‘What am I prepared to do now?’”

Robert M. Franklin Jr.

James T. and Berta R. Laney Professor in Moral Leadership

‘First, you must be willing to look’

At the Legacy Museum, Monique Newsome stands before an interactive screen — one of the few exhibits that requires visitors to decide if they want to engage with it.

She hesitates.

A message cautions that the exhibit presents a series of harrowing photographs of actual lynchings. The EJI has documented more than 4,000 racial terror lynchings of African American men, women and children between 1877 and 1950.

Their research identifies lynchings not only in the South, but in California, Oregon, Minnesota, Montana, Kansas, West Virginia, New Jersey and beyond. The photos illustrate a public spectacle meant to provoke terror, affirm power and restore racial hierarchy following the Civil War.

As Newsome touches the screen, disturbing images spin past: black bodies tortured, burned, dismembered, and hung from bridges, tree branches and power poles. But Newsome is equally stunned by the white faces gathered to watch — crowds numbering into the hundreds, even thousands.

Their expressions are stern or impassive, defiant and proud. Some photos would later be made into commemorative postcards. One cautions: “This is how we protect our homes.”

“It’s like a carnival of carnage,” murmurs Newsome, the wife of Candler graduate Chauncey Newsome 99T, shaking her head.

But it’s important to look, she insists. To understand, you must first be willing to look.

Entering the Legacy Museum, visitors are immediately reminded where they are. Emblazoned across a wall a sign reads, “You are standing on a site where enslaved people were warehoused…”

The compact space overflows with data-rich interactive exhibits, photography and artwork that illustrate how slavery evolved through eras scarred by lynching, Jim Crow laws, racial segregation, chain gangs and mass prison incarceration.

Throughout the exhibit, the faces of visitors radiate pain and disbelief, anger and empathy. “My grandparents are from the South,” explains Brandeis Tullos, a third-year master of divinity student and Candler student body president. “The legacy of hurt and the devastation? Folks don’t really talk about that.”

“We like to think this only happened in the South, but it actually spread so far. We don’t even know how many people died,” she adds. “It’s like the secret no one wants to talk about.”

Although Candler invited pastoral care experts on the trip to provide emotional support, conversation doesn’t come immediately. “First, there is just an overwhelming sense of the pain — pain yet to become fully articulated,” Franklin explains. “We are all searching for words.”

During the visit, students who’ve never met Love approach her to offer their thanks. A staff member falls into her arms, nearly sobbing. “There really aren’t enough tears to sufficiently grieve this experience,” Love acknowledges.

The healing act of acknowledgement

After a few hours — everyone begs for more time — the buses transport the group to Montgomery’s First United Methodist Church. While some gather for a lunch prepared by parishioners, others head to the sanctuary for quiet reflection.

Charles Hamilton, a third-year master of divinity student interested in pursuing military chaplaincy, is already processing what he’s seen. “I came here wanting to learn more about the history of lynching, but I also wanted to pay homage to my ancestors,” he says.

“Memorials like these stir emotions — but knowing these lives have not been forgotten brings some comfort,” he explains. “Part of you wants to condemn people, but in the end, so many sides were hurt by this trauma.”

“It’s through the healing act of being able to acknowledge the past that we move forward,” he concludes.

The day’s last stop is a modest brick building located steps away from Alabama’s State Capitol: the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church. It was here, from his basement office, that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. helped lead the 13-month-long Montgomery bus boycott, a major victory for the American civil rights movement.

The Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church is located just down the street from the Alabama state capitol building.

The Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church is located just down the street from the Alabama state capitol building.

Imagine a warm summer Sunday, Franklin says, and a small church with no air conditioning. “They would throw open the windows and from his pulpit, Dr. King could look straight out and see that Confederate symbol of power,” he says.

In fact, it was there, in the sprawling Greek revival building that Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as the president of the Confederate States of America. As the group begins boarding the buses, the Rev. Dr. Letitia Campbell lingers on the sidewalk, quietly studying the church.

She smiles.

“To see this humble church in the same block as the state capitol reminds you that power can be small,” observes Campbell, assistant professor in the practice of ethics and society and senior program coordinator of the Laney Legacy Program in Moral Leadership.

‘It all starts with truth’

Days later, about 30 students gather in Brooks Commons in Emory’s Cannon Chapel to talk about the trip — among a series of conversations that will continue for weeks.

“As we know, last Saturday was a powerful experience for us as a community — I know I’m still processing it,” says Quentin Samuels, assistant director of student life at Candler. “Now’s a time to share what’s on your minds, your hearts, your spirits.”

“What was the first emotion that bubbled up when you visited the museum, the memorial?” he asks.

Horror. Indignation. Grief. Rage. A white student recalls feeling physically sickened, but also guilty. A black student admits she was overwhelmed by the long legacy of hate-fueled violence. “Has that really changed?” she asks. “Are we ever going to heal?”

A faculty member describes feeling pierced in her soul. “The pervasiveness of lynching created a deep capacity to see this fully and not respond to it,” she says. “Where are the theological ideas that allowed people to see suffering, to participate in suffering, and not act differently?”

“What is it that allows people to see violence against black and brown communities and resolve it without being transformed?” she asks.

Threads of this dialogue will wind into classrooms, casual conversations and faculty meetings for weeks, spilling over into events planned for next semester. Like the loamy soil of a freshly tilled field, they will continue to nurture the growth of ideas, new understandings.

One student admits relief that he didn’t recognize any names at the memorial. “But just because they weren’t there doesn’t mean people weren’t affected by the terror,” he acknowledges. “There is a danger in forgetting, a danger in denial. And that pushes me to a place of hopeful vocation.”

“The work we are called to do is wondrous — and tough,” he adds. “It reminds me that we can’t have healing and reconciliation without justice and truth. It all starts with truth.”

For some, the trip provokes as many questions as it has answered, both spiritually unsettling and personally challenging. For others, it has provided depth and dimension, shaping a foundation for understanding.

Beneath it all, lessons will linger — carried forward with these students out into the world, like seeds lifted on the wind.

Learn more:

Please visit Emory University, Candler School of Theology and the Emory News Center.