The Flu is Coming

Are we ready for the next pandemic?

Infectious disease experts have had plenty to worry about in recent decades, including HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and Zika. But one disease scares them above all others—influenza. That’s right, the flu.

Even though many people dismiss and misunderstand it—calling everything from a cold to a stomach bug “the flu”— influenza actually claims 12,000 to 56,000 lives in the U.S. every year. And that’s in a normal flu season.

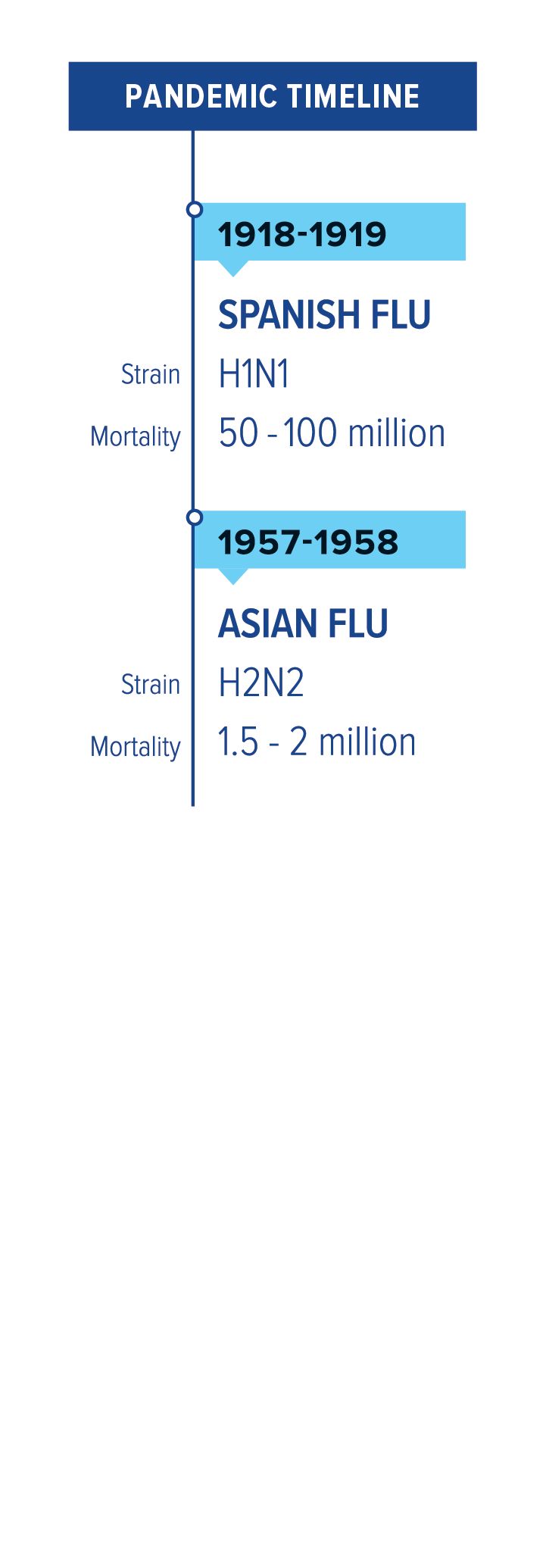

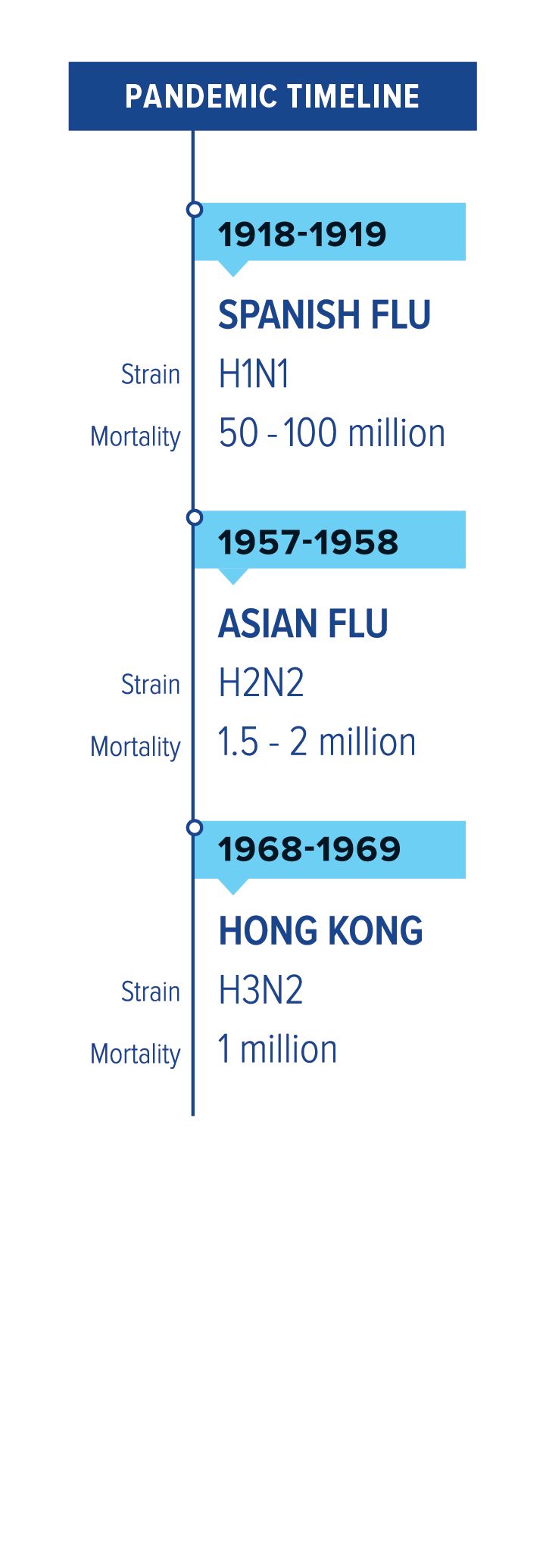

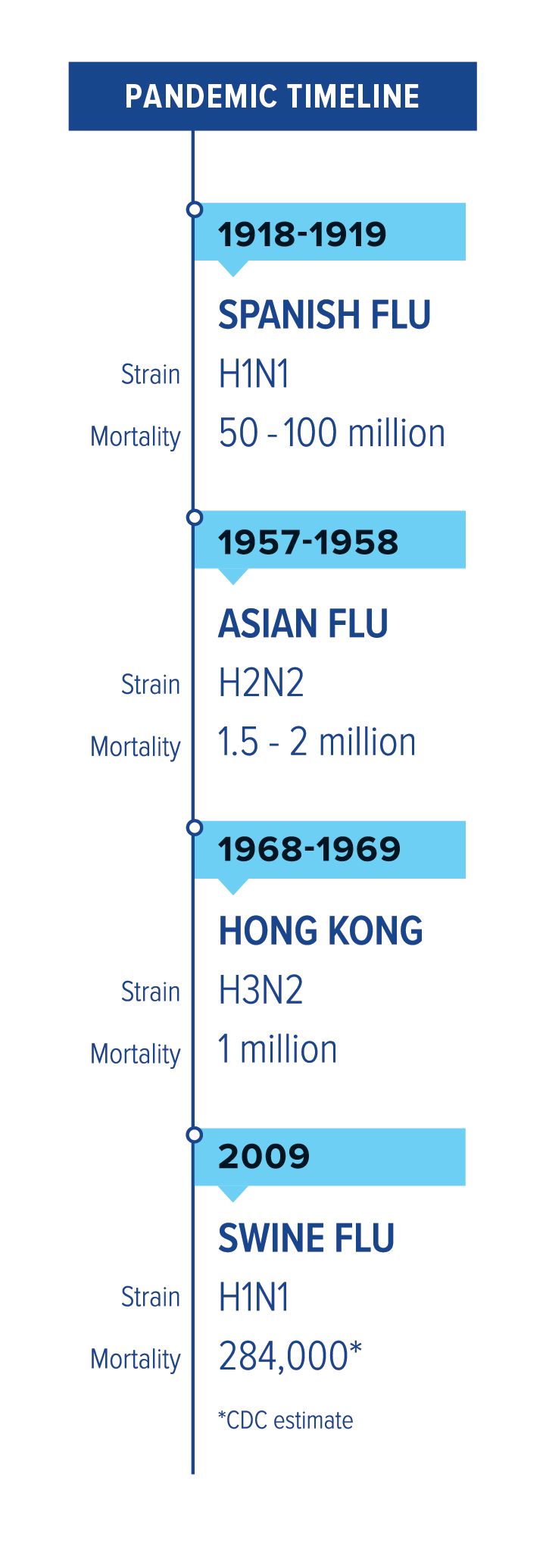

Every so often, a flu pandemic emerges. That’s when a new strain appears that is so different from what has circulated before that people have no immunity to it. A hundred years ago, the 1918 H1N1 pandemic swept the globe infecting about a third of the world’s population and killing 50 million to 100 million people. Since then, there have been three more pandemics, in 1957, 1968, and 2009.

The next pandemic, say experts, is a question of when, not if. Are we ready?

“We’ve come a long way, but we are still vulnerable,” says Ruth Berkelman, emeritus director of the Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research at Rollins School of Public Health. “Influenza spreads quickly. It mutates quickly. And it’s persistent in the environment. I think it’s one of the biggest catastrophic threats we face.”

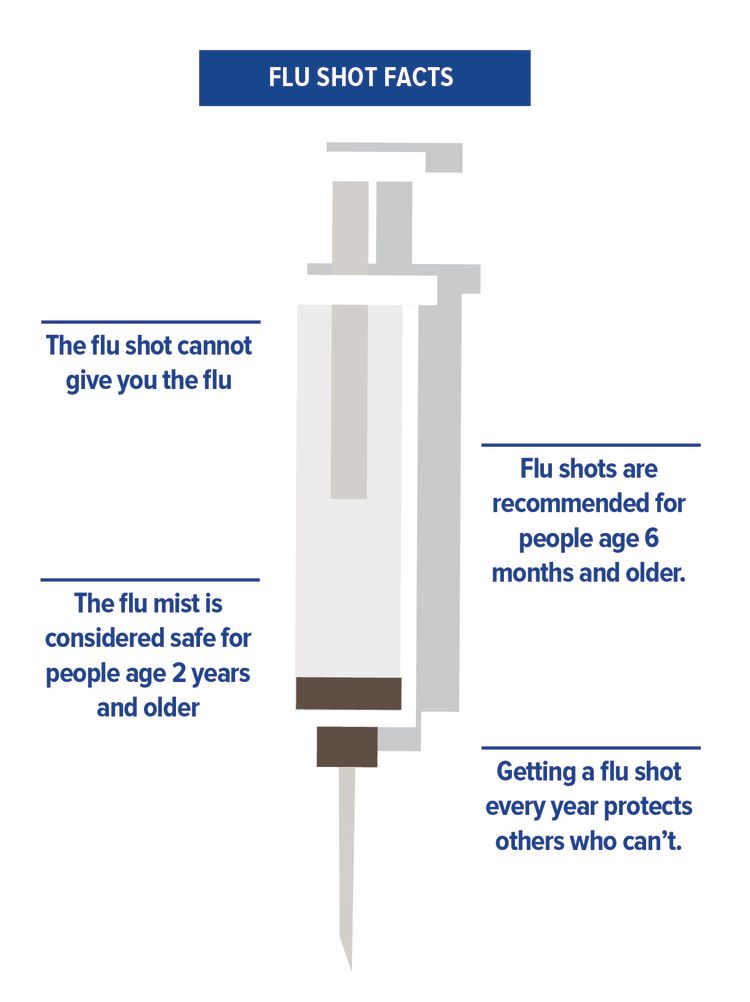

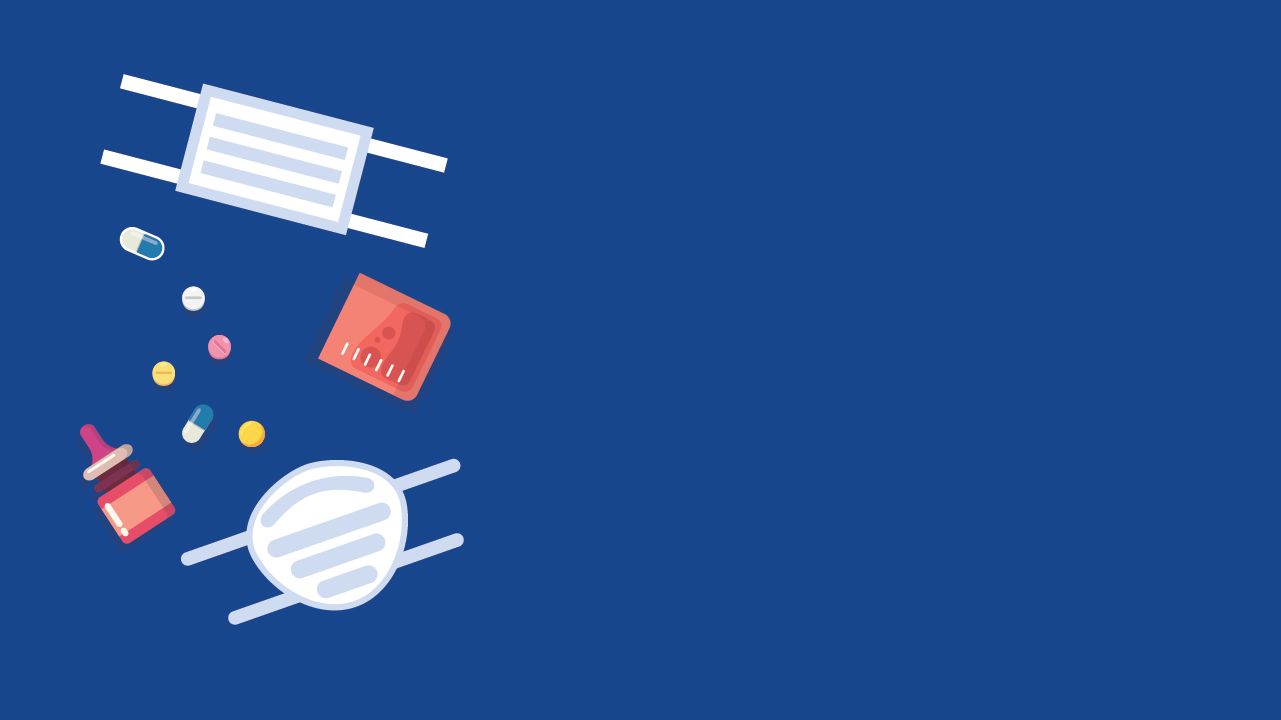

But we have vaccines to help prevent infection, antivirals to cut a bout of flu short, and antibiotics to combat the bacterial infections that often arise after the flu. We’re safer now than ever before, right?

Not really. Influenza is a wily adversary. It hides in its host for a day or so before making its presence known, so the infected person can unknowingly spread the germ to countless others just by going about daily routines of school or work, grocery shopping, or working out at the gym. The virus is contagious, spread largely by droplets produced when those infected sneeze, cough, or talk. Flu germs can leap to other people up to six feet away and linger on hard surfaces for 24 hours.

And, most worrisome, the virus constantly morphs and changes to outwit vaccines.

“You can do a lot to get ready, but at the end of the day, the flu seems to find a way around everything you’ve done,” says Lynnette Brammer, who leads the CDC's domestic influenza surveillance team.

“There is a saying, ‘If you’ve seen one pandemic, you’ve seen one pandemic.’ I know less about influenza today than I did 10 years ago.”

Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota

‘A Mind of its Own’

Brammer has a Game of Thrones-inspired sign in her office that reads, “Flu is Coming.”

“It’s almost like influenza has a mind of its own,” she says. “It’s wildly unpredictable.”

Consider the 2009 pandemic. Flu watchers had been convinced the next pandemic would come from an avian influenza strain out of Asia, but the 2009 outbreak was a strain that circulated among swine, H1N1 (a variant of the strain responsible for the 1918 pandemic), and it emerged from Mexico. The outbreak began in April, when flu is not typically circulating in the Northern Hemisphere.

“It started in such a strange location and at such a strange time of year, taking everyone by surprise,” says Allison Chamberlain, acting director of the Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research and research assistant professor of epidemiology at Rollins. “It just underscores how hard it is to stay ahead of the flu.”

A video about flu facts featuring G. Marshall Lyon, MD, a team member of Emory's Serious Communicable Diseases Unit (SCDU).

That fall, Emory’s Office of Critical Event Preparedness and Response (CEPAR), directed by emergency medicine physician Alex Isakov, coordinated a university-wide response to the outbreak. CEPAR, in collaboration with Emory faculty and other partners, developed the Strategy for Off-Site Rapid Triage (SORT), an assessment of illness severity and risk factors that would allow people to recover in the most appropriate place; home for convalescence or clinic/ER for further evaluation and care. This included housing Emory students who were confirmed or suspected of having Swine flu in a voluntary “quarantine dorm.”

“The residents of Turman South receive free meals, do not attend class, and travel to the pharmacy in a van they call the Flying Pig. Linens are changed daily. A staff member brings grocery bags of Tamiflu, granola, sports drinks, soup, and thermometers. The goal is preventing the infected from sniffling and hacking their way into an epidemic,” wrote Emory College journalism alumnus Robbie Brown, who covered the event for The New York Times in September 2009.

Guarding Against a Shape-Shifter

Influenza’s propensity to shape shift makes formulating vaccines something of a guessing game.

In February, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, with recommendations by the World Health Organization, decides which three or four strains to include in the U.S. vaccine for the next flu season based on which ones have been circulating to that point.

But in the six or more months it takes to produce and distribute a new vaccine, the virus may have morphed into a strain different enough from the original that the vaccine is ineffective. That’s exactly what happened last year, according to Marshall Lyon, an infectious disease physician and a team member of Emory’s Serious Communicable Diseases Unit (SCDU). The federal government has called upon SCDU to care for more patients with special pathogens than any other health care institution in the United States.

According to Colleen Kraft, SCDU associate medical director, Emory has leveraged this expertise to conduct innovative research, validate clinical practice and technology, translate discoveries into training and education programs for healthcare providers and ultimately improve patient care outcomes and worker safety in the event of a pandemic flu or other infectious disease outbreak.

A main focus of Emory’s research is creating a more effective vaccine.

“If I get myself vaccinated but everyone else around me skips the vaccine, I am more at risk,” says Walter Orenstein, director of the Emory Program on Vaccine Policy and Development. “That’s because the general herd immunity threshold for influenza is thought to be 50 percent.”

That means if at least 50 percent of the population is immune, influenza can’t get enough of a foothold to cause a pandemic. So if a vaccine is 60 percent effective, 85 percent of the population would need to get vaccinated to achieve that herd immunity threshold.

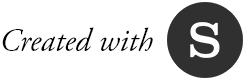

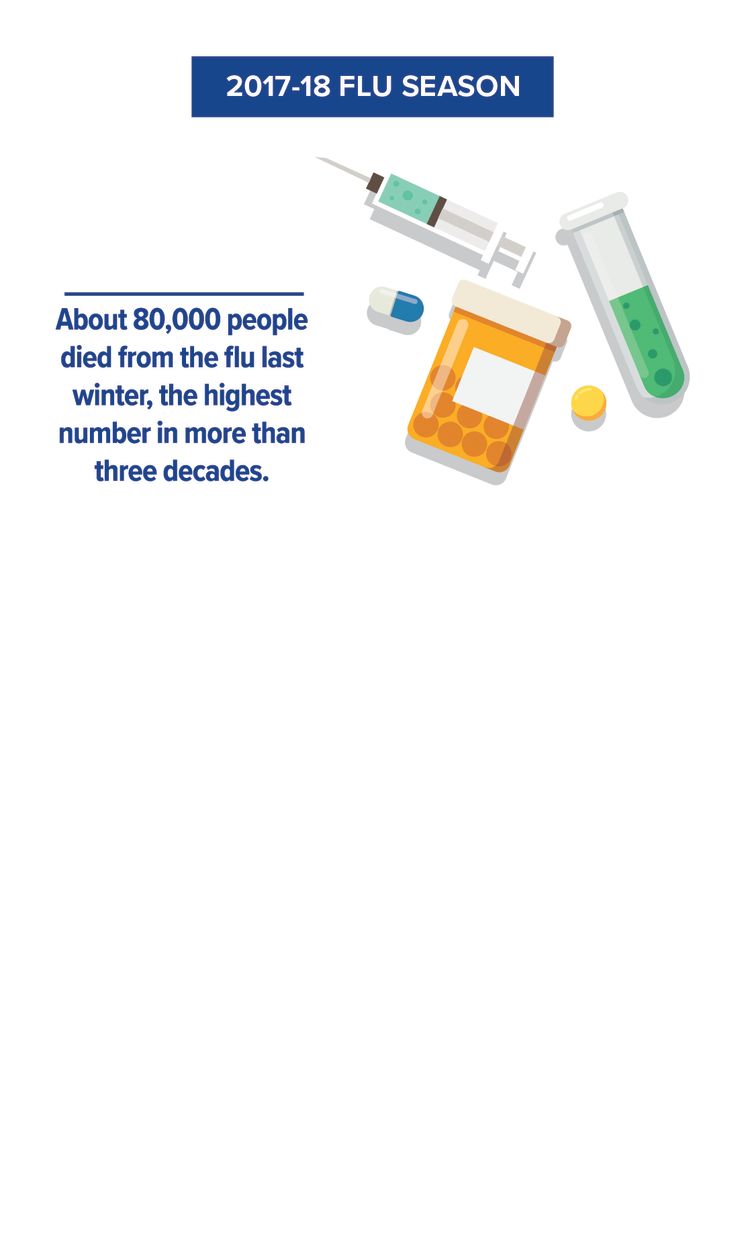

Last year’s flu season was the deadliest in 40 years, killing an estimated 80,000 Americans, including 180 children. The severity of the epidemic highlighted other potential shortcomings. Demand for hospital beds and services quickly outstripped supply. Grady Memorial Hospital was forced to convert waiting rooms into in-patient units, rent “mobile ERs” for the parking lot, and ask staff to work overtime.

Working Toward a Universal Vaccine

The best defense against a flu pandemic would be a universal vaccine—a vaccine effective against all strains of the flu that would last many years, if not a lifetime.

Researchers say such a vaccine is still years away, but important work is being done at Emory, which partners with the University of Georgia as one of five Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance (CEIRS). These five centers are responsible for pandemic planning for the U.S. government.

The two main types of influenza virus that infect humans are A and B. Both are associated with seasonal epidemics, but only type A viruses have caused pandemics.

Influenza A viruses are further broken down according to two surface proteins—hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). These proteins on the cell’s surface are like identifying fingerprints, unique to that virus. Small mutations in either of these proteins result in a new subtype, which is why flu vaccines have to be updated annually. A bigger mutation could result in a strain that humans haven’t encountered before, so they lack any immunity to it. And that could lead to a pandemic.

The HA molecule—the most predominant—is shaped like a tree, with a large head and a smaller stem or stalk. The head is what binds the virus to cells, and it’s also the part that changes from year to year. Influenza vaccines usually target the head of the HA.

Rafi Ahmed, director of the Emory Vaccine Center.

Rafi Ahmed, director of the Emory Vaccine Center.

Rafi Ahmed, director of the Emory Vaccine Center, is working to develop a vaccine that targets the stalk of the HA molecule. Since that region does not tend to change from strain to strain, a vaccine that disabled the virus by attacking the stalk would work for many, if not all, strains of influenza A.

Ahmed and his team started down this road after the 2009 pandemic, when they made the surprising discovery that people infected with the H1N1 strain produced antibodies that attacked the stalk region, not the head. That opened the door to developing vaccines that do the same.

“We’ve been able to identify many antibodies that bind to the stem region and also to some conserved areas of the head,” says Ahmed. “We are collaborating with Mount Sinai to develop a vaccine, but we are still in the early days.”

Ahmed’s lab is also looking at what could be done to make the vaccine long-lasting, be it adding another compound, altering the design, or using a different delivery method.

Emory researchers Ioanna Skountzou and Chinglai Yang working together during the 2009 flu pandemic.

Emory researchers Ioanna Skountzou and Chinglai Yang working together during the 2009 flu pandemic.

In another Emory lab, Ioanna Skountzou, associate professor of microbiology and immunology in the school of medicine and a researcher for the Emory/UGA CEIRS, is taking the novel approach of targeting the virus’s NA molecule, which changes less frequently than HA.

She is also using a method that doesn’t rely on growing the live virus in eggs. Instead, she is using a virus-like particles (VLPs). VLPs are man-made decoys of natural viruses that are not infectious, making them safer to produce and less likely to cause side effects. Skountzou’s lab has produced VLPs that express NAs on their surface and has already begun testing them in mice with promising results.

The next step will be to administer the vaccine(s) into the skin using microneedle patches in collaboration with Texas Tech University.

Monitoring Birds and Pigs

Since experts agree that a universal vaccine is still some distance away, Emory researchers are also preparing for an influenza pandemic without one.

Part of that effort involves surveillance, or monitoring the flu strains that are circulating and looking for new ones, particularly in birds and pigs, where pandemic strains tend to emerge. Emory partners with Harbin Veterinary Research Institute to monitor live bird markets and bird and swine farms in southeastern China. The work is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and expensive, and involves sending people into the field to collect samples that are then brought back to the lab to analyze.

Walter Orenstein, director of the Emory Program on Vaccine Policy and Development.

Walter Orenstein, director of the Emory Program on Vaccine Policy and Development.

“Surveillance is like an insurance policy,” says Orenstein. “It’s a hard thing to sell and it’s often the first thing cut when budgets get tight. But it’s essential to be able to catch a pandemic strain as early as possible so a vaccine can be produced and distributed.”

Several Emory labs are trying to identify the factors that make an influenza strain more virulent—better able to jump from birds or pigs to humans, and able to pass easily from human to human. By finding the puzzle pieces that make a strain more threatening, researchers can watch for the emergence of those characteristics in circulating strains, potentially getting a jump on identifying a new pandemic strain.

Flu watchers are particularly concerned about a bird flu strain that has been circulating in China since 2013. The highly pathogenic H7N9 strain has evolved to be able to jump from birds to humans—typically on poultry farms or in live bird markets—and it kills about 40 percent of the people it infects. So far, it can’t spread from person to person, but if it were to gain that ability, it would pose a serious threat for a pandemic.

Emory’s Hope Clinic and Emory Children’s Center are testing H7N9 vaccines based on the strain that circulated in China last year. They had already tested a H7N9 vaccine based on the first wave of strains found, but strains from the fifth wave, which circulated last year, are not neutralized by the previous vaccines. So they are back to the drawing board to develop a vaccine that can tackle the latest strain.

The center is recruiting volunteers to test this vaccine. People who would like to participate should call 404-712-1371.

“Without a universal flu vaccine, we can only chase the virus and try to predict it.”

Florian Krammer, associate professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

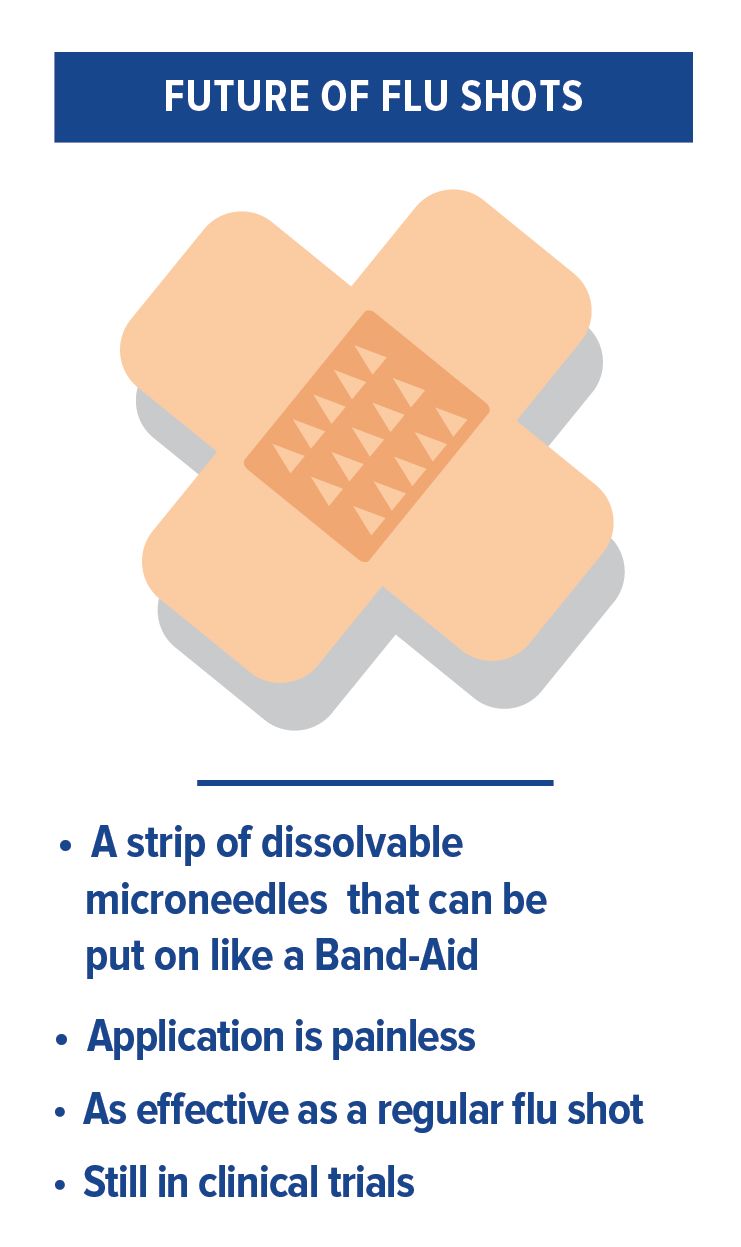

Advantages of the Flu Patch

In collaboration with Georgia Institute of Technology, Emory researchers are testing a vaccine patch. The patches have microscopic, barely-visible needles on their surfaces that are coated with a vaccine. Applying the patch is painless, and the skin acts like an amplifier, boosting the immune response. Since the microneedle patches don’t have to be refrigerated, can be shipped easily, and can be self-administered, they could be a valuable tool in a pandemic.

Pandemic preparedness efforts such as these need to be maintained and sustained, but government funding sources tend to be plagued with short attention spans.

Starting in 2001, there was 9/11, then anthrax, then West Nile, then SARS, says infectious disease physician Julie Gerberding, director of the CDC from 2002 to 2009. “That set the stage for a period of investment in public health that was unprecedented," she says.

The government set up preparedness plans. The CDC held tabletop exercises. The Secretary [of Health and Human Services] visited 50 states for flu summits to plan for a pandemic. "It was a time of remarkable cross-governmental, cross-sector engagement with substantial financial investment at the federal level," she says.

"I feel really sad looking at what has happened since," Gerberding says. "We are looking at 50,000 public health jobs lost and budgets declining over time. Preparedness has to be a sustainable function—it can't be year to year, crisis to crisis."

Indeed, once we are facing down a flu pandemic, it will already be too late.

Pregnancy and Flu

Influenza is particularly dangerous for pregnant women. Changes to a pregnant woman’s immune system, heart, and lungs means the flu can get very serious very quickly, causing dangerous complications like pneumonia and even death. A bout of the flu can also lead to preterm delivery and stillbirth.

That’s why doctors and influenza experts say it’s important for pregnant women to get the flu vaccine, specifically in the form of the inactivated flu shot. The nasal vaccine, made from a weakened live flu virus, is not recommended. “We have very good evidence at this point that flu vaccines are safe for pregnant women,” says Saad Omer, professor of global health and epidemiology at the Rollins School of Public Health. “And the vaccines not only protect the mother, there is strong evidence to suggest they protect the babies in their first four months of life, before they are able to be vaccinated.” For answers to all your questions about vaccination during pregnancy, visit MomVax.org.

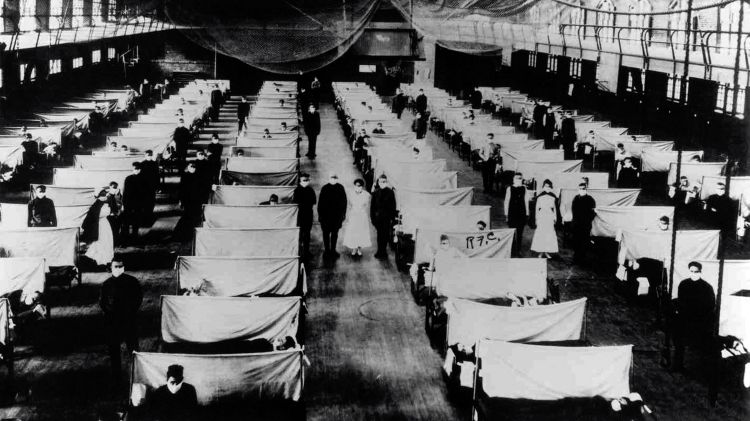

History’s deadliest pandemic

The pandemic that would become the deadliest disease outbreak in history started out mildly. The first wave hit in the spring of 1918, causing the usual chills and fevers. The second wave was a different story. The H1N1 strain that crashed over the world in the fall of the same year was the stuff of disaster movies. Many of the victims were young, healthy adults—people who typically do not die from the flu. And these previously healthy patients often died within hours or days of developing horrifying symptoms—their skin turned blue, they often coughed up blood, and their lungs filled with fluid that caused them to suffocate.

“You could be well at breakfast, sick at lunch, and dead at dinner,” Robert Gaynes, an infectious disease professor in the Emory School of Medicine, told the audience at a Rollins/CDC pandemic conference.

With no vaccines or antivirals, the disease quickly spread to all corners of the earth, helped by the movement of troops in World War I. It came to be known as the Spanish flu, not because it originated in Spain but because the Spanish press widely covered it. News outlets in countries that were embroiled in the Great War downplayed the outbreak for fear it would hurt morale.

“Never in American history has the government tried to control information as much as it did in World War I,” said John Barry, author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History and a speaker at the pandemic conference. “The Surgeon General said there was no cause for alarm. Media and government officials all said no big deal.”

Of course, people knew they were being lied to because they saw the flu strike down co-workers, neighbors, and family members.

In the absence of truthful information, hysteria ensued. “Some people were actually starving to death because others, even family members, refused to visit them and bring them food,” said Barry.

According to accounts of the time, communities imposed quarantines, ordered citizens to wear masks, and closed public places such as schools, churches, and theaters. Businesses shut down because so many workers were stricken. Towns ran out of coffins.

The Spanish flu’s lethality stemmed from an unusual feature. Influenza viruses normally bind to the nose and throat, which is why they spread so easily. The 1918 H1N1 strain, however, not only bound to the upper respiratory track, it penetrated deep into the lungs, damaging tissue and often resulting in a deadly viral and bacterial pneumonia. Upon examining the lungs of deceased victims, pathologists of the day said they had only seen damage like this from victims of poison gas.

By the time the pandemic died out in the spring of 1919, 50 million to 100 million people had died in a 15-month span. That’s more than the number of people who died in World War I, and possibly both world wars combined. It’s more than the number who have died of AIDS since it emerged. The H1N1 strain responsible for the devastation did not go away, but it evolved into a much milder seasonal flu.

Flu 101

Two main types of influenza virus infect humans, A and B. Both are associated with seasonal epidemics, but only type A viruses have caused pandemics. Influenza A viruses are further broken down according to two surface proteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA).

There are 18 different HA subtypes and 11 NA subtypes, and they combine to cause different strains—H1N1, H3N2, etc. Small mutations in either of these proteins results in a new subtype, which is why flu vaccines have to be updated annually. A bigger mutation could result in a subtype that humans haven’t encountered before, so they lack any immunity to it. That situation could lead to a pandemic.

Future threat

The strain that is currently causing flu experts most concern is H7N9, an avian virus, “bird flu,” that began circulating in humans in China in 2013. It started as a relatively mild virus, but it morphed into a much deadlier variety in its fifth wave. During a spike of infections last year, three-quarters of the people who got it ended up in intensive care and more than 40 percent died.

The good news is that H7N9 can’t spread easily from human to human. Most of the people who have contracted it got it from direct contact with infected birds, typically at live bird markets. If H7N9 develops the ability to hop from person to person, however, it could cause a worldwide pandemic.

Where to get your flu shot

You can get flu shot at your primary care doctor’s office or at these Emory Healthcare network partners: MinuteClinic, Peachtree Immediate Care, and Smartcare Urgent Care.

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Healthcare, Emory News Center, and Emory University, Emory Health Digest.

![[object Object]](./assets/ss6iw4qUw0/flu-2-100-750x1242.jpeg)