Working

side by side

Community Benefits Report 2018

EMORY | WOODRUFF HEALTH SCIENCES CENTER

Charity care at Emory Healthcare

These and countless other cases tell the story of heartbreak and devastation that patients face day in and day out. Time and again, caring and compassionate people at Emory work together side by side to meet these patients' needs and make it possible for them to resume their lives after the initial crisis has passed.

In fiscal year 2017-2018, Emory Healthcare provided $98 million in charity care to patients in its hospitals and clinics. Charity care is defined as indigent care for patients with no health insurance, not even Medicaid or Medicare, and no resources of their own. For patients with some coverage, charity care also may come into play when they need catastrophic care, which happens when health care bills are so large that paying them would be permanently life-shattering.

To illustrate what charity care means on a human level, following are stories of patients whose lives were touched by health care teams working together to help them survive their illness and move forward with their lives.

(Patient stories are real, but names and identities have been changed to protect their privacy.)

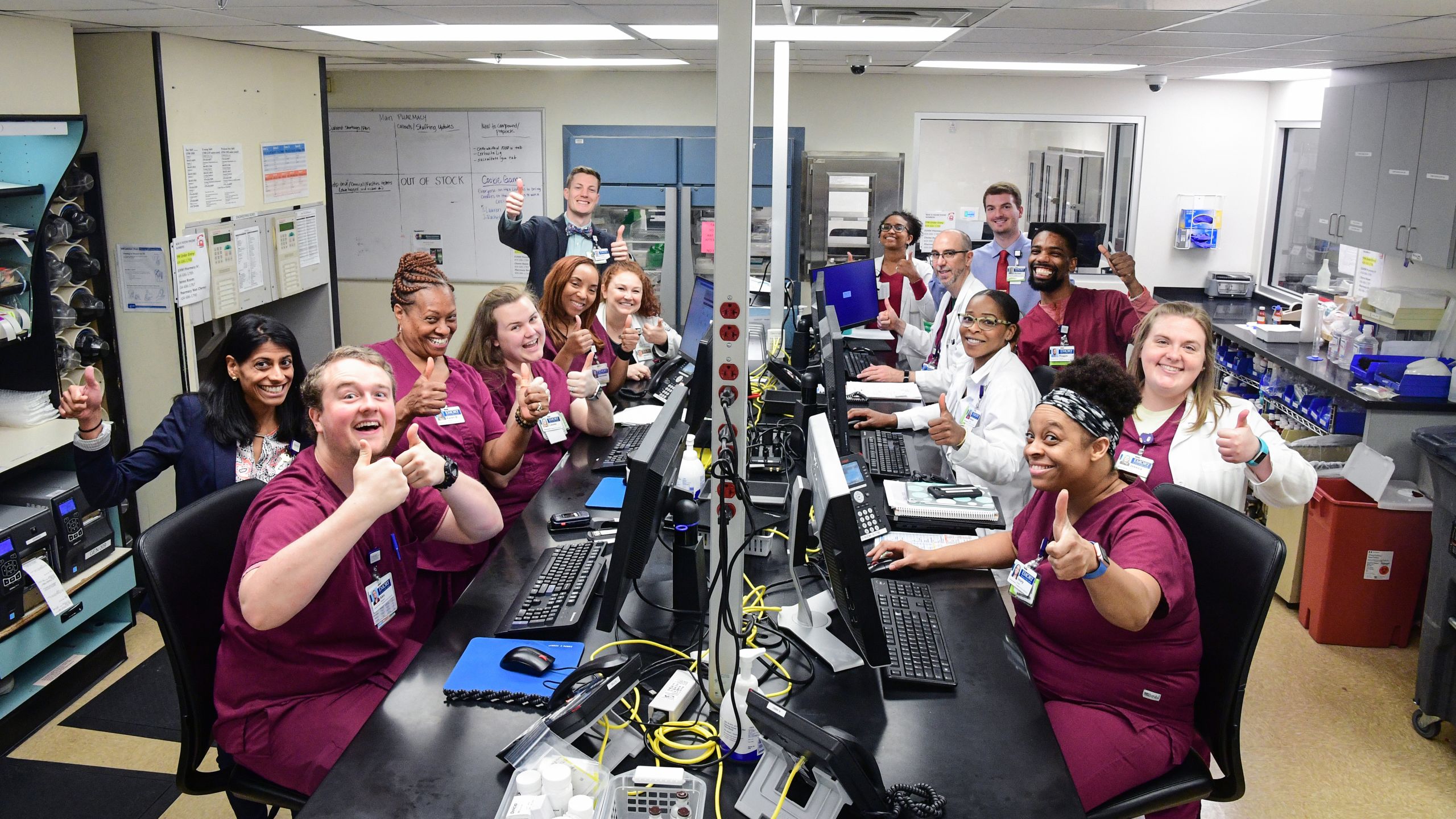

Pharmacy staff and trainees at Emory University Hospital Midtown represent just one of countless teams working side by side—on the front lines and behind the scene—to help patients recover.

Pharmacy staff and trainees at Emory University Hospital Midtown represent just one of countless teams working side by side—on the front lines and behind the scene—to help patients recover.

In disaster, courage (and support) count

Brad West was tireless. He rushed home from his landscaping job to work in his own garden, play basketball with his son, volunteer at church. When he developed fever and chills, the 35-year-old assumed he would soon shake it off. But he had never before faced streptococcal bacteremia (and never found out where the uncommon infection came from). By the time he got to Emory University Hospital, the bacteria already had released chemicals in his bloodstream, setting off inflammatory responses throughout his body, lowering his blood pressure and reducing the heart’s ability to pump blood to vital organs.

Despite a course of increasingly stronger IV antibiotics and blood pressure support, West’s condition rapidly worsened. At one point, his heart spiraled into an abnormal rapid beat, requiring the ICU team to shock it back into a stable rhythm. Shortness of breath progressed to reliance on a mechanical ventilator. Dialysis was initiated to support his kidneys. Dry gangrene began spreading across his arms and legs as his skin and soft tissue died from lack of blood. Halting deadly spread of the infection would require amputation. Surgeons Thomas Dodson and Robert Fang were called in to save the young man’s life.

After two months of intensive care, the bacteremia was gone, and West’s heart, lungs, kidneys, and other organs had recovered. But he now had to learn to cope without his legs and arms. His bravery, determination, and unquenchable good nature and the support of his wife and extended family in the face of this disaster had an enormous impact on the team caring for him, including Dodson, ICU doctors Kate Nugent and Prem Kandiah, bedside nurses, ICU social worker Courtney Faulkner, physical therapist Primrose Mlilo, occupational therapist Rebekah Kirk, and speech therapist Stuart Schleuse. They encouraged West as he healed and prepared to get his prosthetic limbs. Since West had no insurance, Emory set in motion his application for Medicaid. In the meantime, the hospital wrote off more than $770,000 in bills.

When the patient's body began failing from the virulent infection that seemingly came out of nowhere, it took a team, including ICU physician Kate Nugent, to keep him going.

When the patient's body began failing from the virulent infection that seemingly came out of nowhere, it took a team, including ICU physician Kate Nugent, to keep him going.

Hospitalist Willie Smith (with social worker Shonda Knox) says the hospital stay can seem like the least complicated part of what a patient needs to keep doing well.

Hospitalist Willie Smith (with social worker Shonda Knox) says the hospital stay can seem like the least complicated part of what a patient needs to keep doing well.

Continuing care after hospitalization

Before Myra Collins arrived at Emory University Hospital Midtown’s emergency room, she had been living in a personal care home. An aunt checked in on her regularly, but Collins required more care than she could provide. The 48-year-old woman could barely see, was hard of hearing, and had moderate cognitive disability.

At Emory Midtown, she received swift, textbook-perfect treatment for rectal cancer, including surgery and chemotherapy. Collins seemed to settle in. She smiled when doctors and nurses asked her how she was doing, and she responded to the warmth and patience of the nurses teaching her about her colostomy.

Soon, she was in stable condition. According to protocol, she was ready for discharge, with the need to return for daily outpatient radiation and follow-up on her colostomy. But her care team did not believe, given her challenges and the limits of the personal care home where she had been living, that she would be able to manage logistics of transportation, appointments, and colostomy care. Her case was presented at the hospital’s Complex Patient Care Committee, headed by Willie Smith, medical director of care coordination. The committee, consisting of various clinicians and social workers, routinely sees patients like Collins whose complex personal situations create “barriers to discharge.” The committee works hard to find ways to overcome these barriers and ensure all patients have a safe discharge back into the community or to another level of care.

After hearing Collins’ case, the committee decided she could leave the hospital—but not return to where she had been living. Oncology social worker Shonda Knox arranged a six-week stay in a closer, more experienced personal care home. She also coordinated transportation for Collins’ various medical appointments. Medicaid and Medicare had paid Collins’ medical costs while she was an inpatient. But from the moment she checked out, housing, transportation, medical, and other costs all were paid by Emory Midtown. The hospital arranged for Collins to receive mail-order colostomy supplies at no cost and is now working with Collins’ relatives to see if Medicaid/Medicare will agree to let her stay in the personal care home that has been so helpful. It’s all part of getting patients well.

Walking on her own

It was another low-key Friday evening, with a favorite TV show about to start, when Louise Levine’s husband heard a garbled yell. He found his wife on the kitchen floor, moaning, one hand to her head. When he tried to help her up, she stumbled, and her left arm hung uselessly. At Emory University Hospital, Levine was diagnosed with intracranial hemorrhage, the least common but most dangerous type of stroke. She was barely 25, but hypertension and lupus had increased her risk.

The neurosurgical team repaired the torn artery, relieving pressure on the brain. After a week of acute care, it was Emory Rehabilitation Hospital’s turn. Over the next three weeks, a team of physical, occupational, and speech

therapists worked with Levine seven days a week, under the direction of physiatrist Samuel Milton.

Occupational therapist Beth Terrell did the initial evaluation, determining what assistance Louise needed to bathe, get dressed, go to the bathroom. Levine knew her left leg was weak, but she seemed completely inattentive to her left arm, as if she didn’t recognize it as part of her body. Terrell had seen this before with stroke patients. She taught Levine to pay attention to the “dead” arm, positioning it to protect her elbow and wrist joints and using a sling to protect her shoulder. With lots of help from the therapy team, Levine slowly regained the ability to walk, talk, and eat. With her right hand, she could brush her teeth and use her cell phone. Her memory and problem solving improved.

Given her devastating diagnosis, her family considers her recovery a great success. Part of the credit goes to the hard work of Louise, her husband, and sisters, who attended the hospital’s family education sessions to learn how to help with therapy and modify the home environment.

But none of her recovery would have been possible without tens of thousands of dollars in care at Emory University Hospital and Emory Rehabilitation Hospital. Since the young couple had neither insurance nor savings, there would be no reimbursement for these services. Except, says Terrell, for that smile on Levine’s face as she left, walking on her own.

Occupational therapist Beth Terrell was part of a team of physical, occupational, and speech therapists who got the patient back on her feet again after a hemorrhagic stroke.

Occupational therapist Beth Terrell was part of a team of physical, occupational, and speech therapists who got the patient back on her feet again after a hemorrhagic stroke.

When the patient's insurance provider said she had no coverage, hematologist William Blum worked with others at Winship to make sure she got the care she needed.

When the patient's insurance provider said she had no coverage, hematologist William Blum worked with others at Winship to make sure she got the care she needed.

In the patient's corner

When Luella Smith got sick, really sick, she requested medical leave from the call center where she worked. Just a few weeks, until she felt stronger. Three days later, she was told she had acute myeloid leukemia.

At Winship Cancer Institute, the 45-year-old was scheduled for a bone marrow transplant. Then the notice arrived. Her insurance would no longer pay her medical bills. The company belatedly had realized that Smith was no longer working—and that she had not applied or paid for coverage through COBRA, a federal law that allows employees to continue employer-sponsored insurance for a limited time after leaving work.

Smith was confused. COBRA? She didn’t remember anyone ever mentioning this. Since she was on medical leave, she thought she had coverage. No? How could she reimburse the insurance company for what they had already paid Emory? And how would she pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for the scheduled transplant and long recovery time?

Hematologist William Blum and the transplant team stayed focused on Smith’s medical case. Financial counseling manager Adam Yasin took up her financial case. After a review of her income (none) and resources (few), her expenses were deemed charity care, meaning Emory Healthcare would not be reimbursed. Now, as Smith recovers from a successful transplant, Yasin is acting as her advocate, helping her appeal to be able to sign up for COBRA retroactively, based on not having been given a proper opportunity to do so when she left. If she succeeds, her insurance company will pay for medical costs incurred. If she is not allowed to begin COBRA, then Emory Healthcare itself will cover her medical costs, including the transplant.

Yasin says, “She’s sick and without many people in her corner. Emory wasn’t going to abandon her.”

Identifying all viable options

When the normally talkative 20-year-old suddenly grew silent and confused, his cousin brought him to the emergency room at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital. Tests showed that Samuel Oni had suffered a stroke. Unable to swallow, he was given a nasogastric feeding tube. He was also diagnosed positive for tuberculosis.

After months of care by neurologists, infectious disease specialists, surgeons, hospitalists, nurses, and therapists, Oni regained most of his cognitive function and began to walk. He no longer required hospitalization—but someone needed to be with him at all times.

When his cousin could not take him in, social worker Shatima Greer set out to find a place for him to go. Shelters weren’t a possibility, and no one from Oni’s large Nigerian community could find a place with around-the-clock supervision. Finally, Greer called Oni’s father in Nigeria. He loved his son but was terrified by feeding tube responsibilities. Time passed. By the time his feeding tube could be removed, Oni had been in the hospital almost three months. Now he can come, said his father. The hospital paid for airline tickets for Oni and an employee of the medical transport agency who would accompany him.

The day before departure, the agency realized that Nigeria required visas, which their employee didn’t have. Greer didn’t take time to be furious. She called the father, who found an Atlanta friend of a friend of a friend, who had dual citizenship and was willing to accompany Oni. A week later, thanks to the hospital, he was headed home with a month’s supply of medicines and a plan established by Greer through the county health department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to assure that he continued TB treatment.

Oni’s student visa had expired because of a missed paperwork deadline, leaving him ineligible for federal resources during his 90 days of hospitalization and medical care. That left the hospital on its own for almost half a million dollars in unreimbursed costs. But Greer recently checked in with Oni, who is doing much better and sends everyone many thanks.

When the patient's complex condition left him with no place to live, social worker Shatima Greer never gave up on finding him a good home.

When the patient's complex condition left him with no place to live, social worker Shatima Greer never gave up on finding him a good home.

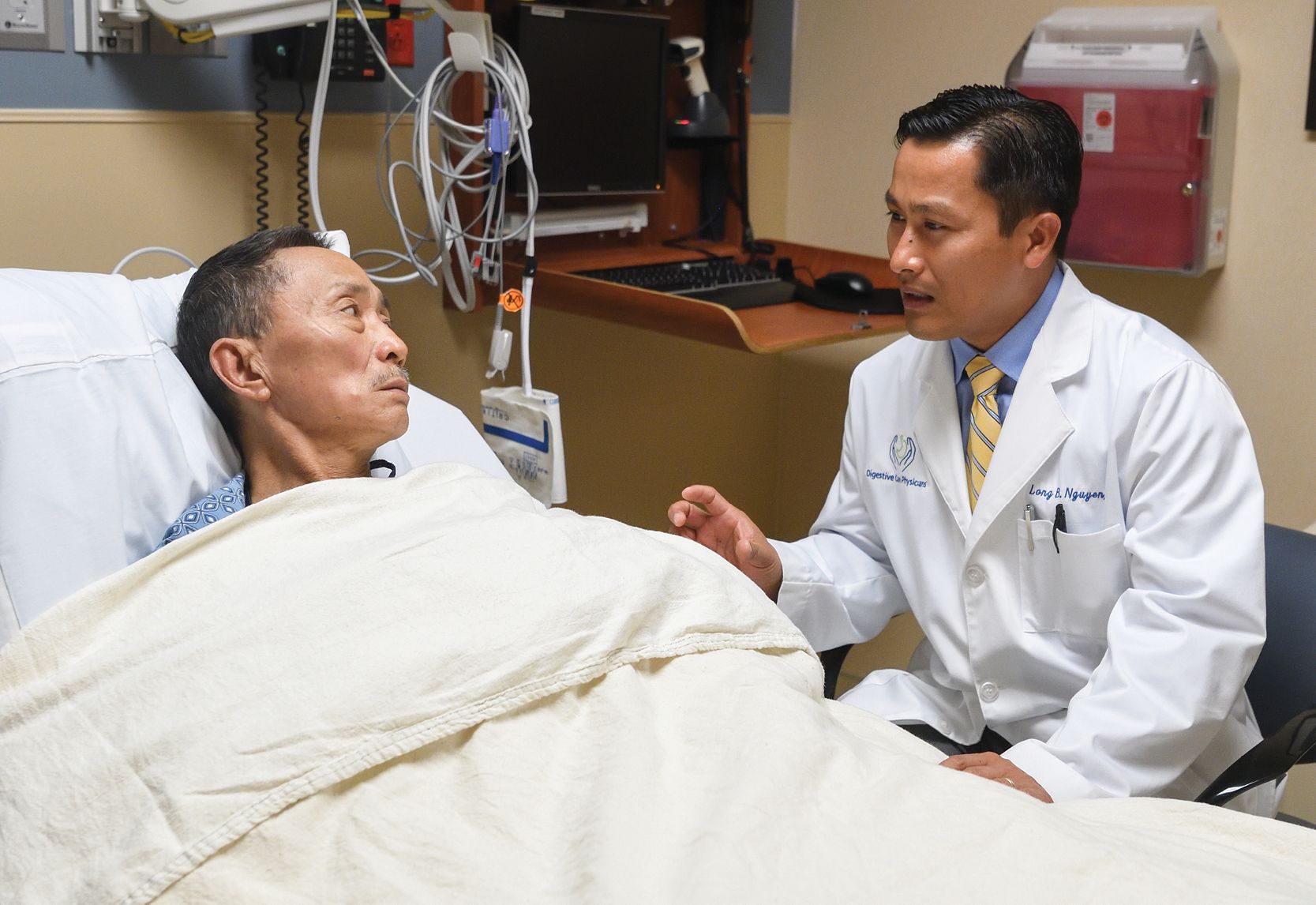

Gastroenterologist Long Nguyen (here with a different patient) was part of a large team of doctors, nurses, and social workers who stood by the mysterious couple.

Gastroenterologist Long Nguyen (here with a different patient) was part of a large team of doctors, nurses, and social workers who stood by the mysterious couple.

Comforting a couple in need

The couple appeared at Emory Johns Creek Hospital emergency room Alone. They spoke no English. Diagnosis of the woman’s condition proved the easiest part of the riddle. Cirrhosis and hepatitis C. Obstructed blood flow to the liver. Poorly functioning kidneys.

But who were these people, this woman in pain, with yellowed eyes and swollen belly, this distraught man? Using the hospital’s translation line, the Korean interpreter was unable to learn very much. The wife, Seo-Yun, had been treated at another hospital but never went back. That was it.

Over the next 18 months, the couple returned 12 times. The devoted husband always slept by his wife’s bed. His wife always encouraged her husband to eat from her tray.

As clinicians led by gastroenterologist Long Nguyen worked on care, social workers led by Catherine Crumrine tried to help with resources. She found that the couple was ineligible for government benefits since their visas had expired. (Perhaps that was why they were so private.) The husband, Joo-Won, spoke of a son—such a good boy, so devoted—but he never called. Was he still in Korea? Estranged? Deceased? Imaginary?

What was real was the care. Dr. Nguyen saw the woman every admission, as did an entourage of cardiologists, nephrologists, hospitalists, and nurses. Seo-Yun was too sick for surgery, but the fluid in her abdomen was drained several times, relieving pressure and pain. The social work team tapped the hospital’s HUGS Fund and the generosity of pharmaceutical companies to get medicine. Concerned nurses pooled their own money to make sure the husband was eating properly.

The two disappeared regularly, then suddenly reappeared, out of nowhere, Joo-Won literally falling to his knees and grasping the hand of the clinician or social worker in gratitude. After Seo-Yun died in the hospice arranged by Crumrine, Joo-Won disappeared for good. What remained was $480,000 dollars in unreimbursed costs—and a sense of satisfaction that the doctors, nurses, and social workers had done all that they could do for this sad and mysterious couple.

Widening the treatment window for stroke

Ben Foster thought he was dreaming. He couldn’t move his right side. A woman in bed next to him was yelling, but he couldn’t understand her, couldn’t quite recall her name.

Foster’s stroke had occurred at night, meaning no one knew the last time he had been OK. The doctor at the local hospital told his frantic wife that too much time had passed for an intravenous infusion of tPA to dissolve the blood clot causing the stroke. That treatment window closed after

4.5 hours. Her husband needed a specialist who could remove the clot by snaking a catheter up through the large artery in the thigh to where it was blocking blood flow to the brain. Foster’s doctor called Raul Nogueira, director of the neuroendovascular service at Grady Hospital, to say the 68-year-old was on the way.

The Marcus Stroke & Neuroscience Center at Grady has one of the largest thrombectomy programs in the country, performing more than 300 such procedures a year. One of the country’s most experienced interventional neurologists, Nogueira also recently helped change the guidelines for use of thrombectomy, as co-principal investigator of a large, multi-national clinical trial.

Previous guidelines had recommended that clot removal take place within six hours of stroke onset. The clinical trial found that thrombectomy could make a significant difference in outcomes in properly selected patients even when performed up to 24 hours after a stroke began.

For years, even before the study, Nogueira had asked families if they wanted thrombectomy, the best he or anyone could do to try to prevent the almost certain devastating result of severe strokes. No one had ever refused. For many, the decision significantly improved recovery. As the new guidelines increase thrombectomy by an estimated 40% nationwide, thousands will have access to those same better results.

Foster gained some movement right after the procedure. Three days later, he was walking independently and talking to the woman whose name he hoped never again to forget!

Neurologist Raul Nogueira helped change the guidelines to expand use of thrombectomy after stroke.

Neurologist Raul Nogueira helped change the guidelines to expand use of thrombectomy after stroke.

Psychiatrist Aliza Wingo translates her research on molecular mechanisms underlying PTSD and depression into concrete recommendations to increase emotional well-being for the many veterans she treats every year.

Psychiatrist Aliza Wingo translates her research on molecular mechanisms underlying PTSD and depression into concrete recommendations to increase emotional well-being for the many veterans she treats every year.

Treating PTSD and depression

Like many of the veterans whom psychiatrist Aliza Wingo sees at her clinic at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Joe Ritchie had symptoms of both Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and depression. Wingo wants to understand how the two conditions interact. Why are some people resilient in the face of traumatic events, while others, like Ritchie, struggle to cope and sink into depression?

Some of the reasons may be genetic. Wingo and her colleagues have discovered that among genes regulating the stress response, one is significantly less active in patients with simultaneous PTSD and depression than in people without this double diagnosis. Another genetic variant discovered by her team, a gene in the brain’s reward circuitry, is connected to positive emotions. Wingo hopes understanding these mechanisms will point to treatments that will increase the 35% improvement rate now seen with medication and psychotherapy for patients like Ritchie.

Ritchie’s PTSD and depression can be traced to his experiences in the battlefield. These include three years of mortar and rockets, having to bag bodies after IED explosions, and the unexpected suicide of his best friend. When Wingo first examined him, she looked for anxiety and mood disorders, suicidal thoughts, substance abuse, and other risk factors. She also assessed protective factors like a supportive family, belonging to a religious community, strong social networks, even having someone to talk to.

In addition to state-of-the-art treatment, she recommended that Ritchie develop hobbies and activities he enjoys, helping him set goals and make social connections. “Get sufficient sleep, exercise frequently, set small goals for yourself,” she advised, “all of which will help you cope with stress.”

It’s working. And Wingo’s research continues on psychological well-being (having positive emotions, inner peace, life satisfaction, a sense of purpose and meaning in life), its genetic and molecular mechanisms, and its ability to mitigate risks not only of PTSD and depression but also of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke, and dementia.

Collective efforts to serve patients and the community

Few people in Atlanta’s history have ever made such a lasting impact as our center’s namesake, Robert W. Woodruff. It was largely his vision, leadership, kindness, and generosity that helped make Atlanta a dynamic, world-class city with a highly diverse and rapidly growing population.

That dynamic population brings increasingly complex health challenges to which no one medical professional can possibly have all the answers. Instead, modern health and healing require interdisciplinary, interprofessional teams working side by side across education, research, and clinical care to most effectively prevent and treat disease.

Working side by side harnesses the extraordinary talents of our medical professionals, educators, and investigators to improve quality of life for all the people we serve. Through the collective efforts and dedication of our entire Woodruff Health Sciences Center, we provide value to our patients and our community and help ensure continued health and well-being for the city, the state, the region, and beyond.

Jonathan S. Lewin, MD

Executive Vice President for Health Affairs, Emory University

Executive Director, Woodruff Health Sciences Center

President, CEO, and Chairman of the Board, Emory Healthcare

Jonathan S. Lewin, MD

Jonathan S. Lewin, MD

Want to know more?

Please visit the 2018 Community Benefits Report, Emory Healthcare, Emory News Center, and Emory University