Who was Atticus Finch?

Letters from Harper Lee shed new light on the beloved and now controversial character

By Laura Douglas-Brown | April 5, 2018

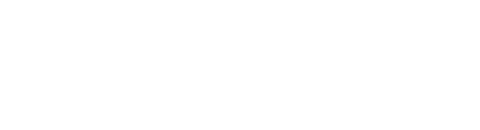

For more than 50 years, Atticus Finch stood as one of the most beloved characters in American literature, the model of a principled white man who spoke out for racial justice and a gentle father who guided his children by example rather than through fear.

A central character of Harper Lee’s acclaimed novel “To Kill a Mockingbird,” published in 1960, Atticus is a lawyer in the small town of Maycomb, Alabama, who earns the ire of some white townspeople — and the admiration of his young daughter — when he defends a Black man, Tom Robinson, accused of raping a white girl and facing an all-white jury.

Known by her nickname, Scout, Jean Louise Finch is Atticus’s daughter and the novel’s narrator. Spirited, precocious and usually clad in grubby overalls, she idolizes her father and finds in him the acceptance she is already learning can be hard to come by under the rigid social rules that govern Maycomb and the world beyond.

Generations of American readers, many of whom read “To Kill a Mockingbird” for school assignments during their own formative years, grew to love both characters. And many reacted with something akin to grief when “Go Set a Watchman” — the only other novel known to be written by Lee — was published in 2015 after the manuscript was found in a safe-deposit box by the elderly writer’s lawyer.

Written before “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “Go Set a Watchman” is also set in Maycomb, and also explores the relationship between Atticus and Jean Louise Finch. Here, though, Jean Louise is a young woman who has moved to New York City and is returning to Maycomb for an annual visit that mostly serves as a reminder of how different she is from the place she once called home.

Even her father, it turns out, is not who she thought he was, as the novel reveals that the same Atticus who defended a Black man accused of rape (in this version of the story, actually winning an acquittal, unlike in “To Kill a Mockingbird”) is a member of an all-white Citizens Council formed to oppose integration.

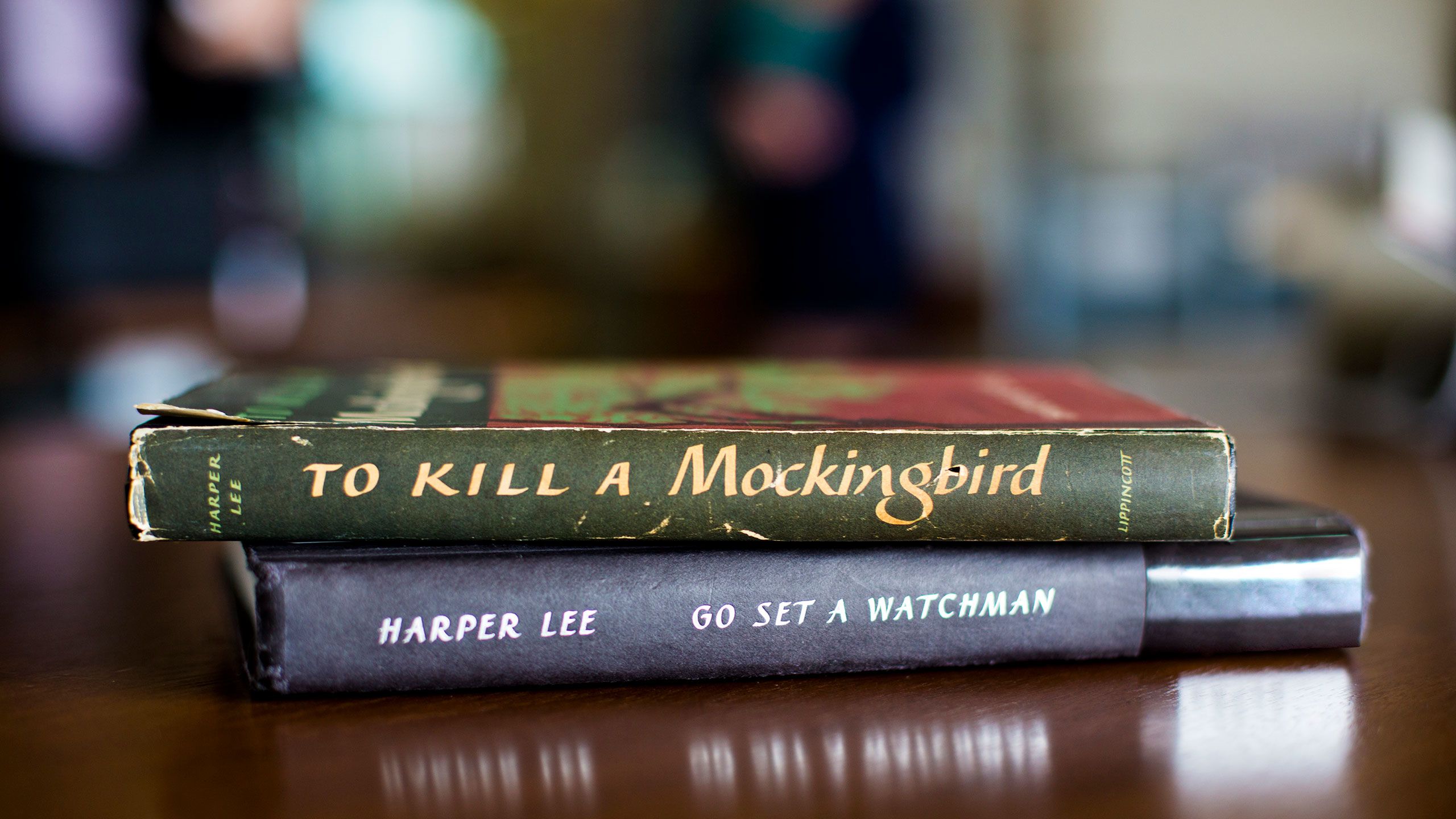

Now a collection of Lee’s letters acquired by Emory University helps shed light on these two versions of Atticus Finch by illuminating Lee’s relationship with her own father, long recognized as a model for the character.

The letters, spanning 1956 to 1961, offer glimpses into Lee’s life during the crucial years when she was writing “Go Set a Watchman” and writing and publishing “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and echo major themes from both novels.

“When ‘Go Set a Watchman’ was published, there was a lot of controversy over these two different versions of Atticus Finch,” says Joseph Crespino, Emory’s Jimmy Carter Professor of American History and author of “Atticus Finch: The Biography,” to be published in May 2018.

“These letters give us insight into Harper Lee’s personal life and what was going on in her hometown that would have inspired her to write these two different versions — the kind of conflicts she was trying to work out in her fiction,” Crespino explains.

Emory acquired the letters from retired attorney Paul R. Kennerson of La Jolla, California, who said he approached the university about becoming the permanent home of the archive after meeting with Crespino, who reached out to him while researching his book on Finch.

“These letters complement the research being done by Joe Crespino so perfectly that I was taken with the fit of it and was highly impressed with other work being done at Emory,” Kennerson notes. “I can’t think of a better place to house these materials for future use by researchers and scholars.”

The "Paul Kennerson collection of Harper Lee material, circa 1947-1980s" is now available to scholars through Emory's Rose Library. View the Finding Aid for more details.

The "Paul Kennerson collection of Harper Lee material, circa 1947-1980s" is now available to scholars through Emory's Rose Library. View the Finding Aid for more details.

Now available to researchers and students by appointment in Emory’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, the letters bridge several of the Rose Library’s strongest areas of focus, including modern literature, African American life and culture, and Southern history and politics, notes Rosemary Magee, who served as Rose Library director when the letters were acquired.

“Harper Lee’s own life story, as revealed through the letters, occurs at a particular moment in history where lines are being re-examined and redrawn,” Magee notes. “As with her characters, we see Lee struggling in her own community; we enjoy her playfulness with language; we observe her devotion to good friends.

“In short, we recognize a young woman coming to terms with her times and her talent.”

A tale of two fathers

“To Kill a Mockingbird,” which won the 1961 Pulitzer Prize for Literature and cemented Lee’s place in the American canon, offers an idealized view of Atticus through the eyes of the young Scout: He is deeply moral, fair and kind, a man who earns respect from the African American community for his work to defend Tom Robinson, a father who guides his children to follow in his footsteps.

“The book has this almost unique place in our popular culture in the way that it serves as a kind of primer for so many white young people in learning the history of racial discrimination and racial inequality in the American South, but also having this model of racial morality,” Crespino says.

So for many readers, the contrast between the Atticus of “To Kill a Mockingbird” and the Atticus of “Go Set a Watchman” proved painfully jarring, almost like a betrayal, he explains.

The Atticus of “Watchman” is “condescending to his daughter, he says these terrible things about African Americans in the 1950s, he’s opposed to the changes going on — it’s such a polar opposite perspective from the Atticus that we have come to know and love,” Crespino says.

But instead of two separate characters, these versions of Atticus are meant to be viewed as two sides of the same person — and Harper Lee’s father, Amassa Coleman “A.C.” Lee, was the inspiration for both, he explains.

“One of the things that I have discovered by going back and doing research on Harper Lee’s father is that it is clear that he was a complex individual who would have inspired both versions of Atticus,” Crespino says.

Like Atticus, A.C. Lee was a lawyer and state legislator; he was also the owner and publisher of the newspaper in Monroeville, Alabama, the town on which Maycomb is based.

“There are plenty of things from his own past that are noble, where he takes a stand morally and speaks out on the editorial page for these kinds of important principles, and yet he is also a white Southerner living in rural Alabama in a time of great change, who resents and is opposed to many of the dramatic political and social changes that are transforming his home,” Crespino says.

Harper Lee sits with her father, A.C. Lee, on the porch of his home in Monroeville, Alabama. The character of Atticus Finch is based on A.C. Lee. Photo by Donald Uhrbrock/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images.

Harper Lee sits with her father, A.C. Lee, on the porch of his home in Monroeville, Alabama. The character of Atticus Finch is based on A.C. Lee. Photo by Donald Uhrbrock/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images.

The letters now housed at Emory offer important perspectives into Harper Lee’s feelings about her father, and therefore her famous character.

They are written from Monroeville, first when she has gone home in 1956 to help care for her father following a major health crisis, and then from later visits. Addressed to her friend Harold Caufield, a New York City architect, as well as Michael and Joy Brown, who helped finance her writing life, the letters are alternately witty and tender, showing Lee grappling with the realization of her father’s mortality.

“Sugar, I guess we all rise somehow to occasions: I’ve done things for him that I never remotely thought I’d be called on to do for anybody, not even the Brown infants, but I supposed there is truth in the adage that you don’t mind it if they’re yours,” Lee writes to Caufield on June 16,1956, later adding, “he’ll get over this, but it’ll take time, time, time, and that’s where I’m needed, and here is where I’ll stay until I’m not needed.”

She offers a similar take in a later missive titled as “Sunday letter” to Caufield: “While thinking of something to say to you I found myself staring at his handsome old face, and a sudden wave of panic flashed through me, which I think was an echo of the fear and desolation that filled me when he was nearly dead,” Lee writes. “It has been years since I have lived with him on a day-to-day basis, and these months with him have strengthened my attachment to him, if such is possible.”

This further evidence of Lee’s attachment to her father speaks directly to both novels, Crespino says.

“One of the things that we learn in these letters is we get a great portrait of the depth of her feeling and love for her father,” he explains. “Of course, her father is the key figure in both of the novels that she wrote.”

In Lee’s letters and in Crespino’s further research, we see both the admiration for her father that informs the young Scout’s view of Atticus in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” as well as the tensions with her father that are the crux of the older Jean Louise’s view of Atticus in “Go Set a Watchman,” where Atticus is also aging and now needs help with daily tasks.

“We can anticipate the way she is going to think about and want to work out in her fiction the very complex set of feelings that she has towards her father,” Crespino notes.

Pivotal time in Southern history

In “Go Set a Watchman,” Jean Louise’s relationship with her father reaches a crisis point when she learns that he is on the board of the newly organized Citizens Council, a group of white segregationists who oppose what they view as interference from the Supreme Court and the NAACP that threatens their way of life.

While the letters in Emory’s collection don’t discuss A.C. Lee’s stands on the Citizens Council, and he likely would have been too ill by then to join, they do confirm that Harper Lee had a front-row seat to Monroeville’s struggles with these issues, and provide important insight into her opinion of the major players in the debate.

“Another key thing that we learn from these letters is we are able to place Harper Lee in Monroeville in an important time in the broader history of the civil rights movement in Alabama and in the South,” Crespino says. “Harper Lee is at home in Alabama in 1956. That’s important to know because 1956 is a critical year in the era of mass resistance in Alabama politics.”

By reading local newspapers from when the letters were written, the historian found that 1956 was the year the first Citizens Council — which he describes as “the white-collar Klan” — formed in Monroeville.

In a letter dated only “Sunday Night After You Called” but believed by Crespino to have been written in 1956, Lee sends Caufield an extensive description of the local political scene, including a man named Henry Lazenby, who she derides as “a singularly spineless creature all his life.”

Although Lee does not mention it in the letter, Crespino’s research shows that Lazenby was the leader of Monroeville’s Citizens Council.

Alienation and identification

Lee’s letters to Caufield and the Browns also illustrate her broader sense of isolation in returning to Monroeville, similar to Jean Louise’s sense that she no longer belongs in Maycomb — her awareness of “a sharp separation” and that “all of Maycomb and Maycomb County were leaving her as the hours passed,” as Lee writes in “Go Set a Watchman.”

In a letter to the Browns dated only “Sunday,” Lee describes the “ecclesiastical gloom that is Monroeville” and writes of how “sitting and listening to people you went to school with is excruciating for an hour — to hear the same conversation day in and day out is better than the Chinese Torture method.”

“These letters give us a good sense of Harper Lee’s feeling of being an outsider in her hometown — this town that she loves and where her family is, but she feels like she no longer has a home there,” Crespino says. “This is a major theme of ‘Go Set a Watchman,’ where Jean Louise comes home, and she is homeless now, because she has changed.”

But despite her own alienation, Lee also continues to defend her home, the South, from those in the North who would see it only as the land of the Klan.

In the final letter in the new collection, written on Nov. 21, 1961, after “To Kill a Mockingbird” was published to great acclaim, Lee writes of her disappointment that Esquire Magazine has rejected a piece she wrote about Southern politics.

“My pastiche had some white people who were segregationists & at the same time loathed & hated the K.K.K. This was an axiomatic impossibility, according to Esquire!” she writes. “I wanted to say that according to those lights, nine-tenths of the South is an axiomatic impossibility.”

To Crespino, the passage shows Lee’s frustration that Northerners can’t accept a more nuanced version of the South.

“That is very much a central theme of this book that we don’t discover until 2015,” he says. “Jean Louise is upset with Atticus, but one of the things that she comes to understand over the course of ‘Go Set a Watchman’ is that Atticus could be a member of the Citizens Council, but that doesn’t mean necessarily that he has thrown in full-bore with the reactionaries of Southern politics. And, of course, as Jean Louise discovers that, Harper Lee intends for the reader to discover that.”

Recalling that “Watchman” was written before “Mockingbird”and that this letter was written after “Mockingbird” has made Lee a literary success, “what is fascinating from these letters is that we understand that Harper Lee is still struggling with that,” Crespino points out. “She still wants to get that message out.”

With these letters now available at Emory, more and more readers will have the opportunity to gain deeper insight into Lee’s takes on family, friendship, politics and publishing.

“Collections such as the Harper Lee letters are invaluable resources for scholars and students of all ages to understand the story behind the story, to gain insight into the relationships that shaped an author and the creative processes and environment that gave rise to a notable literary work,” says Jennifer Meehan, interim director of the Rose Library.

“Preserving these resources ensures that such stories are available for discovery by current and future generations.”