‘Think Young,’ urged his campaign materials, and Ambassador Andrew Young still does

By Susan M. Carini 04G March 1, 2023Considering the impact one life can have, it surely would have been enough to have Andrew Young’s courageous work as executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and front-line lieutenant to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

But Young was just getting started — he would go on to equally full lives as Georgia’s first Black congressman since Reconstruction, the first Black U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and Atlanta’s second Black mayor. Today, he is the chair of the Andrew Young Foundation. All this from the 90-year-old icon, who humbly insists, “I have never known today what my life would be tomorrow. There is nothing I have done where I knew a day ahead of time.”

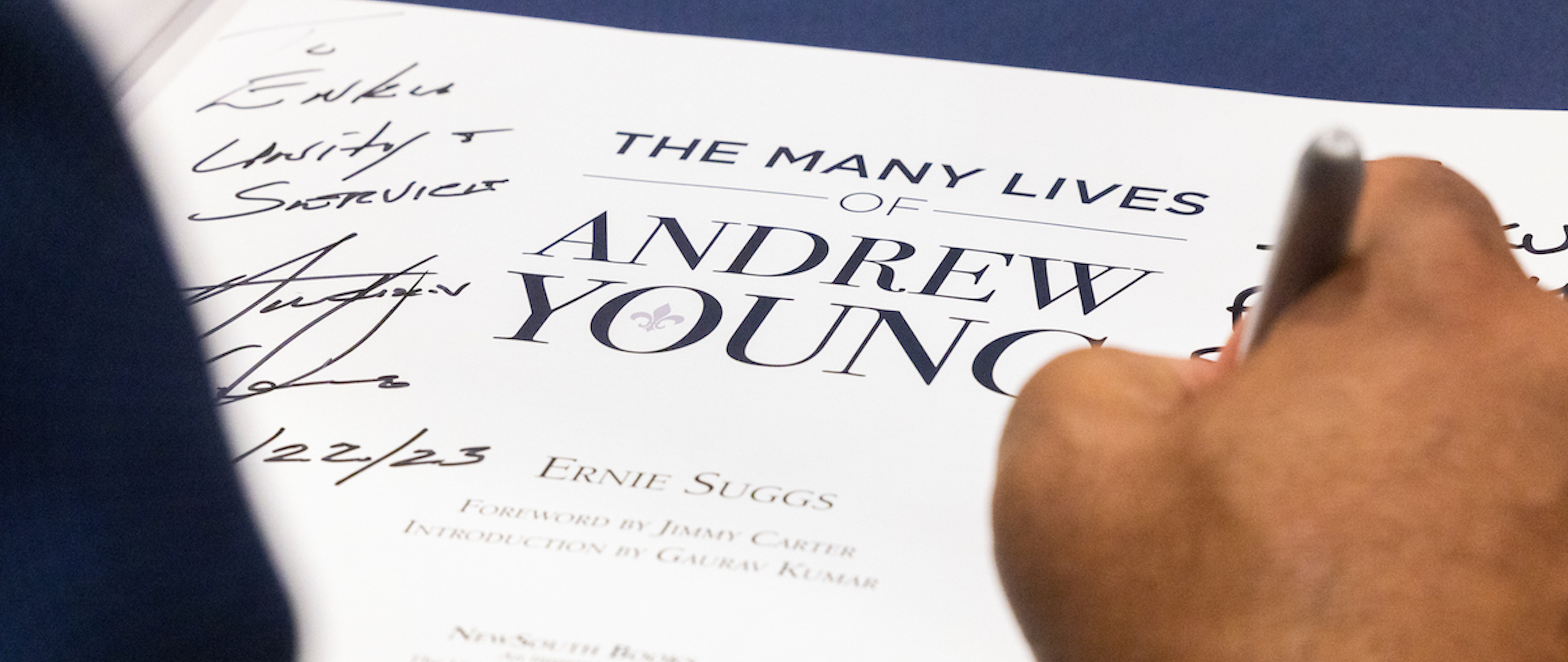

Sharing the stage with him Feb. 22 at the Emory Student Center was the author of “The Many Lives of Andrew Young,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Ernie Suggs. He has covered Young since 1997, penning more than 250 articles that mention him. The event was hosted by Emory Libraries and cosponsored by the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Michael C. Carlos Museum and Decatur Book Festival.

Young’s deep ties to Emory include receiving an honorary degree in 1991 and delivering the Commencement address in 2019, at which he was awarded the Emory President’s Medal. In 2021, he was the keynote speaker at the Carter Town Hall. His grandson Noah is currently a first-year student here.

As Young revealed in a private event beforehand at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, where he was shown papers from the African American collections, “thinking Young” was not just a clever campaign theme when he ran for Congress. It continues. Young is now talking with Emory President Gregory L. Fenves about how the university’s growing expertise in artificial intelligence could be used to tell a fuller story of the civil rights movement.

At the student center, the evening began with Suggs asking about someone on the minds of many, President Jimmy Carter. “He is,” noted Suggs, “a former U.S. president, a man of Georgia, a professor at Emory University and your friend. What is this moment like for you?”

Young quoted Deepak Chopra: “We think that we are human beings who have occasional spiritual experience; in fact, we are spiritual beings living a brief human experience.” He continued: “You kind of know that when you get to be 98. The spirit of Jimmy Carter is something to behold even now.”

The ambassador examines papers from Emory’s African American collections. Clint Fluker (far right), the collection’s curator, told Young: “This is an opportunity for us, as a university, to engage with people in real life to make the world better.”

Glimpses of Young's many lives

Young’s father taught him his first lessons in nonviolence. According to his father, “God created from one blood all the nations of the world. If others believe that whites are superior, ignore them. That is their problem with God. If they do mess with you, don’t get angry. Get smart. Your mind is your most powerful weapon.”

Raised in New Orleans, Young recalls a neighborhood corner that challenged him to understand the experience of others and rein in his emotions when provoked. As he awaited the bus that took him to his segregated school, there was an Irish grocery store, an Italian bar and the headquarters of the Nazi Party. “That is a perfect formula for going to the U.N., and I was just four when I learned that,” Young said.

However, figuring out the best use of his life, and the role of education in it, was problematic. His father, a dentist, wanted him to follow his path, but “I didn’t want to be anything that kept me shut up in an office,” Young confessed.

He was forced to accelerate in school, entering the third grade at age six and college at 15. He was not alone, noting that both King and Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor, had this experience. He theorizes that it was because the Vietnam War had taken too many Black students out of college. The result for Young? “It meant I didn’t have a chance to grow up.”

After a year at Dillard University, he transferred to Howard University but considered the time there “a curse. I wanted to get out and find out what the world was all about. In my last year, I knew that I didn’t know anything.” In fact, he begged his parents not to come to graduation simply because a diploma with his name on it was not a certainty.

He did graduate, and his parents came. On the way back home, they stopped at King’s Mountain, North Carolina. A runner, Young describes testing his stamina on a run up the mountain. Not knowing for sure whether he passed out as he climbed, he made it to the top in bad shape.

As he recovered and contemplated the view, “The world just looked different. ‘Damn,’ I said to myself. Whoever made all this with a purpose could not have failed to make me with a purpose. When I came down from that mountain, I said: ‘One day at a time, I will figure this out.’”

President and Mrs. Fenves enjoying, as a community crowd later did, the unique stories that Ambassador Young has to tell.

Ambassador Young in the Rose Library before addressing a crowd at the Emory Student Center about a book chronicling his many contributions to public life.

President Fenves and Gaurav Kumar, president of the Andrew J. Young Foundation, engage Ambassador Young at a private event in the Rose Library.

Finding his purpose

And he did, going on to earn a bachelor of divinity from Hartford Theological Seminary. He describes that time as yet more training for the U.N.: the seminary was home to people who had been missionaries around the world.

“In 1957, when things started bubbling, some people came to me and wanted me to come South,” Young noted. Upon joining the SCLC, he was presented with an egg crate full of letters that people had written to King. Young’s job was to answer them. “I thought of my main position as being to tell the story of those who were being hunted,” he said.

During his first time in Atlanta, the Ku Klux Klan marched down Auburn Avenue. On his next visit, he was driving down Ponce De Leon Avenue and saw a rat cross the street. He carefully avoided hitting it, saying, “At that time, a rat had more standing than Black folk.”

Change came to Atlanta, in part because of Young, who felt “there was something special about this place. It was all potential.” Young served two terms as Atlanta’s mayor (1982-1990) and is widely credited with establishing the pro-business, dynamic city it is today.

As mayor, he spurred development, presiding over the creation of Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport. During his tenure, the city attracted more than 1,000 new businesses, $70 billion in foreign direct investment and created a million new jobs.

Just as the business community would not RSVP to an integrated dinner supporting King after the receipt of his Nobel Prize, Young too felt an initial coolness from business leaders. “When I was running for mayor, they had decided that they did not want another Black mayor. Maynard Jackson was enough,” he said.

The crowd settles in for what Vice Provost Valeda Dent identified as “stories you probably won’t hear at any other point in time.”

Ernie Suggs, whose work as a reporter has covered Ambassador Young extensively, is the author of “The Many Lives of Andrew Young.”

Nigerian sisters asked the ambassador several questions, charming the audience — and the ambassador — completely.

Ambassador Young gets to know Ivy Allen, a sixth-grader whose mother, Samellia Allen, works at Emory Johns Creek Hospital.

The indifferent student becomes a superb educator

Pupils of Young come in many shapes, sizes and ages. Suggs describes the honor of progressing beyond knowing Young as an elder in the community and a subject of his coverage on the race and culture beat.

“Writing the book, as rich an experience as it was, pales in comparison to being on tour with him. In what feels like a father-son relationship, he is teaching me every day,” Suggs notes.

He points out that, like many leaders who have contributed at such a high level, Young’s achievements are multilayered and diverse, which means that people know him in different ways.

He is a man who was with King on the day he died. But there might be people in Africa who don’t think about his role as a civil rights leader or mayor of Atlanta but instead are grateful to him for bringing resources to their country that improved their lives in some way. All of the chapters testify to how great his life has been.

When Valeda F. Dent, Emory’s vice provost of libraries and museum, introduced Young, she stressed that “for our young people, this is a chance to engage in some deep, first-person learning. The narratives and the stories you are going to hear tonight are ones you probably won’t hear at any other point in time.”

During the Q&A, two Nigerian sisters, one 12 and the other six, eagerly asked questions. The younger sister posed the evening’s final question, asking, “What is it like to be a vice president?”

He did not correct her about his record. Instead, gently, with the experience of having nine grandchildren, Young offered this response:

It’s a hard job. You would do better to be a secretary of labor and see to it that everyone has a good job. Or be secretary of education and see that all our schools work. Maybe you can’t be the secretary of education to start with, so you can be a good teacher. And if you can’t be a good teacher to start with, you can be a good student. You have to do what you know to be right and believe in yourself. And you do, or you would not have expressed yourself so well.