Boyhood DISRUPTED

THE FINE LINE BETWEEN FUN AND DANGER

It started out as a perfect Father’s Day for Chris Harrison. He had everything he wanted that humid Sunday morning in June 2017: a quiet jog, a Waffle House breakfast with his wife, Michelle, and their four kids, and the gift of a blue Walmart vacuum he’d been admiring.

That afternoon, while Harrison was testing out the vacuum, his nine-year-old son, Brayden, slipped outside with his younger sister, Jessica. He wanted to show her that he could climb the entire height of a neighbor’s tree.

When Jessica returned home, she was alone and terrified. “He’s not moving,” she told her dad. “I think he’s dead.” At first, Harrison thought she was talking about the family cat. But then he realized his son was nowhere in sight. “Brayden has always been a daredevil,” he says.

Jessica led him across the street to where her brother lay motionless, face down at the base of the tree. Blood trickled from a cut on his head and from his nose, his right eye was swelling shut, and there was a tennis ball-sized bump on the top of his head.

Desperate to see any sort of movement in his son’s body, Harrison began compressions on Brayden’s chest. Paramedics arrived minutes later and rushed him to the closest local hospital.

Emergency room personnel realized the life-threatening nature of his injury and transferred him immediately to Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. The Harrisons wondered if their son would survive. “It was the longest day of my life,” says Chris Harrison.

Children’s trauma team members started work on Brayden as soon as he arrived, beginning IVs in a warm ER room specially designed for pediatric patients to protect them from metabolic complications of trauma, including hypothermia.

They ordered medications to ease the pressure in Brayden’s head, evaluated his neck, abdomen, and chest with X-rays, and learned from a CT-scan of his head that there was a brain bleed that required immediate surgery.

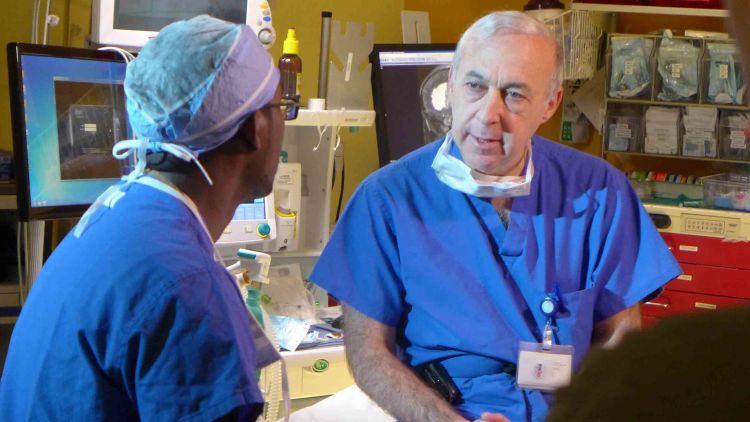

“If left untreated, he certainly would have died,” says Andrew Reisner, Emory pediatric neurosurgeon and medical director of the Children's Healthcare Concussion Program.

“I chose pediatric neurosurgery because I so enjoy working with children,” Reisner says. “They are brave, authentic, and funny. More often than I would like, though, the disease or injury is untreatable and fatal. You have to be prepared for long cases and long work hours. There are no short cuts.”

Brayden’s first craniotomy took about three hours. During the surgery, Reisner temporarily removed a portion of Brayden’s skull bone to locate the source of the arterial bleed and remove a blood clot. He also inserted a probe to monitor his intracranial pressure over the coming days.

Chris Harrison texted updates to friends while Brayden’s older brothers, 16-year-old Justin and 18-year-old Zach, paced the hallway. “I was scared to death, thinking my son was going to die,” said Michelle. After the surgery, Reisner gave the family a tentative thumbs-up. Michelle cried with relief. However, the family was cautioned that they were not in the clear yet and that Brayden still had a long way to go.

The next afternoon, Brayden was taken back to surgery, as Reisner had learned from a follow-up CT-scan that a second, delayed bleed had occurred. The second epidural hematoma—bleeding between the tough outer membrane covering the brain and the skull—was contributing to the raised intracranial pressure and required removal.

Brayden was kept sedated during this critical period of his recovery. “Brain swelling normally gets worse before it improves, often peaking three to five days after a head injury,” says Reisner. This sedation was recommended based on a protocol Reisner and his team implemented in 2011, as it minimizes the pressure.

“Children are not merely small adults,” Reisner says. “Their treatment should be tailored to the unique pathophysiology of head injuries in children. Typically, children are sedated until the pressure in their brain is normalized: below 20 mm of mercury.”

The use of these guidelines has led to a 40 percent increase in survival among children with severe TBI at Children’s Healthcare, and the program's effectiveness was recently reported in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics.

Among survivors, the new guidelines have also led to a general improvement in children’s abilities once the acute brain injury has been alleviated. “This can be evaluated through WeeFIM,” Reisner says, “a measure that assigns children a score based on how independently they can function after an injury.”

The inventory measures performance in three domains: self-care (e.g., feeding oneself), mobility (e.g., walking), and cognition (e.g., the time needed to understand and follow a simple command).

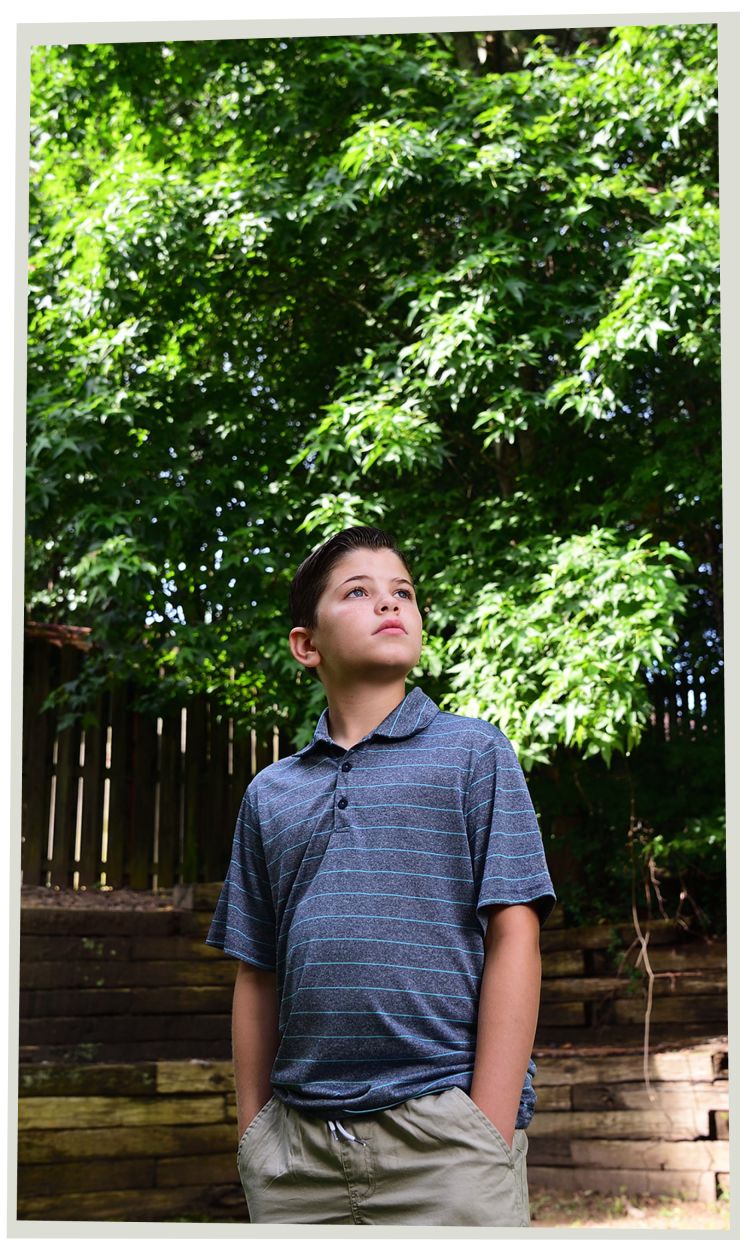

Despite the severity of his injuries, Brayden, now 10, has fully recovered all of his abilities.

“He’s a very lucky kid,” says Michelle Poole, a Children’s Healthcare operating room nurse who worked with Reisner to save Brayden. “We see such sad things sometimes.”

A successful outcome like Brayden’s is the result of the entire care team, which includes emergency room providers, operating room personnel, ICU physicians and nurses, neurologists, ophthalmologists, psychologists, and rehabilitation specialists and therapists, says Reisner.

“All of us had one goal," he says. "To return Brayden back to normal.”

Once it was determined the swelling in Brayden’s brain had subsided, he was weaned off sedation and slowly woke up. Seven days after his fall, his first request was, “Ice, please.”

Then, after taking in his surroundings, including the IV in his arm, he asked, “Am I dead? Am I going to die?”

Every few minutes he would go through the motions, discovering the IVs, asking about his condition, accepting the answer, and then rediscovering the IVs and forgetting why they were there, his father says.

Brayden was also off balance, nearly falling off the bed, and he kept blinking his misaligned eyes, one completely red from a hemorrhage. Everything looked yellow to him, and he saw things in pairs.

He asked for his sister, but Jessica was too terrified to see him, since her mind kept replaying her brother’s fall on repeat. Brayden’s father had the idea of asking his injured son to write his sister a note. Although Brayden was still confused, he agreed to try. At first, he drew a picture, mainly of straight lines. After much effort, he wrote, “It’s me, Jessica, it’s me. I love you, Jessica.”

Brayden was soon moved out of the ICU and into a regular hospital room at Children’s. He was weak, his knees buckling under him on the way to the hospital cafeteria, and he was still stringing out his words. He was irritable and confused, both from the injury and his medications.

But he slowly improved and soon demonstrated he could play air hockey and operate a cell phone. “For a nine-year-old boy, those were crucial signs of hope,” Reisner says.

After he could leave his bed, Brayden and his sister enjoyed watching the koi in the hospital’s garden. “I loved that fish pond,” says Jessica. Brayden remembers getting an army set and a Millennium Falcon model at the hospital.

His father thought Brayden had weeks left in the hospital, but Reisner told them on June 27 that they would soon be on their way home.

“Everyone in the hospital was going on and on about how amazing it was that there wasn’t any permanent damage,” his mom says.

“I told Dr. Reisner goodbye, and thank you for saving my life,” says Brayden.

“I know he was only doing his job,” adds Michelle, “but to us it was so much more.”

Word traveled fast in the Harrisons’ neighborhood that Brayden was home. Friends and neighbors came to visit and to stare in awe at the tree from which he had fallen. The cracked branch towered overhead. The tree is elevated and walled off by thick railroad ties.

“We think his head hit those crossties on the way down,” says Michelle, standing in the tree’s shade a year later.

When Brayden thinks about the event, he can’t remember anything past hearing the branch snap. The “sad thing,” Brayden says, is that he ruined his nicest clothes, a white polo and tan shorts that had to be cut off him.

The only evidence left of the fall is a mark on his back and a thin pale scar on the side of his head where the hair hasn’t grown back yet. He sometimes gets headaches and still takes a minute to think before he speaks, says his mom

Brayden kept up with his classmates at school this past year; he loves science and one of his favorite new books is on the brain and its functions.

Now that it’s summer, he is back to skateboarding, riding bikes, and building model rockets with his dad.

This Father’s Day, the whole family—including Zach, who is now deployed with the U.S. Marines—was in the car on their way back from Cocoa Beach. “It was a much calmer day,” says Chris. “And so wonderful, because we were all together.”

Brayden, now 10, stands in front of the tree he fell from, a year later.

Brayden, now 10, stands in front of the tree he fell from, a year later.

The Surgeon Behind the Mask

Andrew Reisner completed his neurosurgery residency at Emory in 1993. “My mentors included George Tindall and Daniel Barrow, current chief of the Department of Neurosurgery at Emory.”

Since returning to Emory two decades ago, Reisner has been instrumental in the development of the Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and Concussion programs at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Grateful families have established the Andrew Reisner TBI fund, which supports clinical programs and research related to traumatic brain injury and concussion in children.

“I chose pediatric neurosurgery because I like working with children,” Reisner says. “They are brave, authentic, and funny.”

Reisner was recently named the Elaine and John C. Carlos Chair of Neurotrauma at Emory and Children’s. Reisner’s latest quest, through the Children’s Center for Neurosciences Research, is to identify a biological indicator, or "marker," that could be used to diagnose and manage head injuries in children. His collaborators include Emory Assistant Clinical Professor of Rehabilitation Medicine and Children's neuropsychologist Laura Blackwell (below right) and Emory Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine Iqbal Sayeed.

A $466,650 grant from the NIH supports the study of a potential blood biomarker that could detect pediatric traumatic brain injuries, such as a concussion, and its severity.

Determining a biomarker for TBI in children could be a significant step forward, enabling faster and more efficient detection and treatment, earlier intervention in complications, and improved rehabilitation planning.