Community in Action

From dementia to mobile health, the school and its community partners are unified in addressing access to health care

Making African American churches more dementia-friendly

Faculty member: Fayron Epps, PhD, RN, FGSA, FAAN, assistant professor

Partners/Community: African American faith communities

Living with or caregiving for dementia is challenging enough. Layering it with race makes it even more so. Fayron Epps wants to change that.

Established in 2019, the Faith Village Research Lab aims to provide African American caregivers, families, and faith communities with the tools they need to more easily and comfortably access care, education, and research resources related to dementia.

Lab founder and director Fayron Epps knew many African Americans thought of dementia as a “white disease,” but she saw clearly how it more often impacted communities of color — and how often these communities were underserved.

When she arrived at the School of Nursing as an assistant professor, those were the communities she wanted to target, creating culturally responsive programs “for us, by us.”

The Faith Village Research Lab’s Alter program currently partners with more than 45 African American faith communities in 10 states.

To participate, each organization must commit to 16 initiatives, which include training church leaders, making church buildings more accessible, creating special worship services for memory-impaired parishioners, finding new ways to make patients and families feel more accepted, and offering memory screenings, coffee hours, home visits, and respite care.

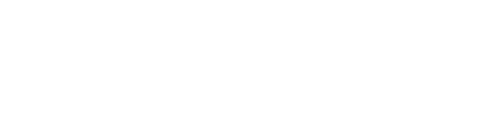

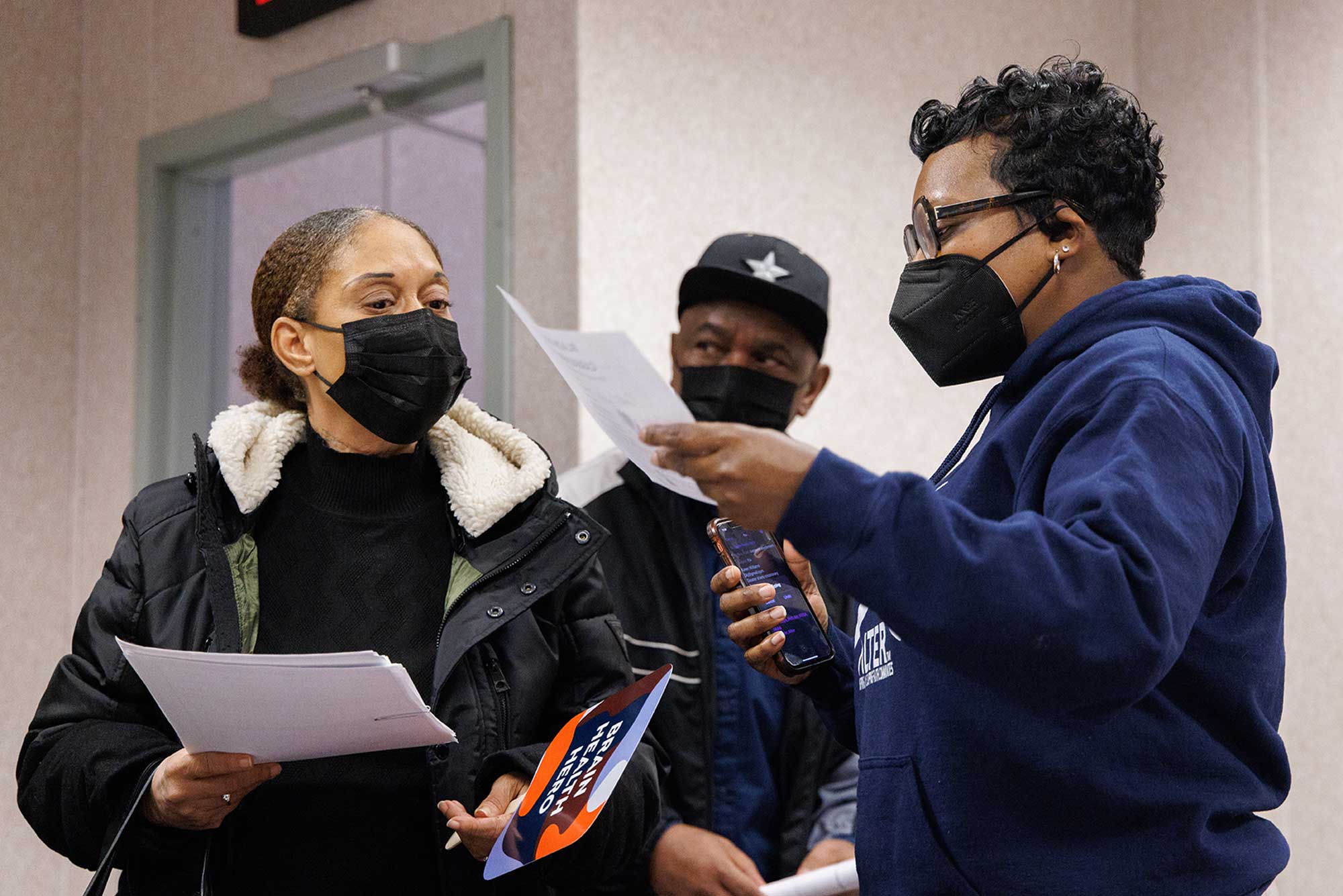

Adrianne Jones speaks at a Columbus, Georgia, event about how to make congregations more dementia-friendly.

Adrianne Jones speaks at a Columbus, Georgia, event about how to make congregations more dementia-friendly.

One of Epps’ most rewarding moments occurred when a woman thanked her for helping her father continue to participate in worship. The daughter was also grateful to participate in research she knew would help others; Epps’ lab connects community members with social science studies and clinical trials.

Alter is conducted in partnership with Georgia State University and supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration and other agencies. — Sylvia Wrobel

Educating clinical instructors and preceptors

Faculty member: Quyen Phan 03MSN, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, assistant clinical professor

Partners/Community: Emory Healthcare, DeKalb County Board of Health, Mercy Care, Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition, Boat People SOS, and other community agencies

Like all professionals, nurses benefit from the guidance of experienced colleagues as they begin their careers. That reality is at the heart of the CAPES Academy, which will recruit and prepare nurses to serve as clinical faculty and preceptors to nursing students and newly licensed nurses in underserved areas of the Southeast.

On a Saturday morning at a free clinic for uninsured and low-income residents in metro Atlanta, School of Nursing student Rebecca Deal 22Ox 24BSN vaccinated a patient for COVID-19. Deal carefully administered the booster shot under the guidance of Deborah Silverstein 78C 83BSN 17MSN 20DNP, FNP-C, her clinical instructor from the Emory School of Nursing, and Thao Nguyen, program coordinator at Boat People SOS.

Nurses like Silverstein play an important role in bridging the gap between theoretical learning and clinical practice for students. The need for more instructors and preceptors is critical to growing the nursing workforce in medically underserved communities — the impetus behind a project at the School of Nursing.

The Clinical Instructor and Preceptor Excellence in the Southeast (CAPES) Academy will prepare 128 licensed nurses to serve as nurse educators in eight states — Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. It is part of an initiative funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration to bolster nursing education through partnerships among academics, clinicians, and community organizations.

Over the next four years, the CAPES Academy will recruit 32 nurses annually. All will receive stipends to complete the yearlong program. Instruction will include online classes, in-person exercises at the Emory Nursing Learning Center, shadowing experiences, and professional development.

Quyen Phan, assistant clinical professor in the School of Nursing, directs the CAPES Academy.

Emory Healthcare, DeKalb County Board of Health, Mercy Care, Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition, and Boat People SOS are among the partners Phan has tapped to provide education and shadowing experiences for CAPES Academy nurses in the Atlanta area. — Pam Auchmutey

Increasing research opportunities for aging and caregiving LGBTQIA+ populations

Faculty member: Whitney Wharton, PhD, associate professor

Partners/Community: Leaders in the local and national LGBTQIA+ community, with support from the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging

Some aspects of aging and caregiving among members of the LGBTQIA+ community are more prominent, less recognized, and too seldom included in clinical research. The RISE initiative helps address those challenges.

As a child, Whitney Wharton watched her parents’ arduous journey as caregivers for her grandmother. It was a powerful introduction to challenges faced by Alzheimer’s patients and caregivers.

Years later, as a cognitive neuroscientist, she recognized that some communities have fewer resources and greater fears about how they are perceived or stigmatized as they age.

Many LGBTQIA+ persons, she found, didn’t know where to find resources for aging and caregiving. Also, many clinicians and researchers did not know the right questions to ask them.

Working with colleagues at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Wharton created RISE (Research Inclusion Supports Equity) to address both challenges. The website includes resources related to aging, living with memory loss, and caring for a family member or friend.

RISE also includes a registry to help ensure that LGBTQIA+ patients and caregivers are better represented in Alzheimer’s and aging research.

Not collecting information about sexual orientation and gender identity can weaken research, Wharton says. The LGBTQIA+ community faces different challenges, especially when race is a factor. LGBTQIA+ individuals are more likely to become caregivers because they are less likely to have children and more likely to live alone.

Caregiving is even more stressful when LGBTQIA+ individuals have not come out to parents or relatives or if families disapprove of their partner or living situation. Close-knit families of choice within the LGBTQIA+ community often have caregiving responsibilities not represented in traditional family dynamics.

Through its website and registry, RISE strives to make health care providers and researchers more responsive to these challenges. — Sylvia Wrobel

RISE leaders Jordan Cook (left), Chloe Jordan, and Whitney Wharton attend the City of Atlanta’s 4th annual Mayor’s Pride Reception at City Hall.

RISE leaders Jordan Cook (left), Chloe Jordan, and Whitney Wharton attend the City of Atlanta’s 4th annual Mayor’s Pride Reception at City Hall.

Boosting clinician well-being

Faculty member: Nicholas A. Giordano, PhD, RN, assistant professor

Partners/Community: Emory Healthcare, Grady Health System, Emory Healthcare Public Safety, and Emory University Police Department

Because of the pandemic, work-related stress and burnout are more pervasive among workers across clinical care settings. An initiative called ARROW — Atlanta’s Resiliency Resource fOr frontline Workers — is helping foster resiliency among frontline workers, including those who care for underserved populations.

Nicholas A. Giordano, an assistant professor in the School of Nursing, is working toward a sustainable systems-level solution as director of ARROW. Through this initiative, health care and other frontline workers are learning how to use mindfulness and compassion-based skills to strengthen self-care.

ARROW is funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration as part of its nationwide resiliency training program. Instruction is free for Emory Healthcare and Grady Health System clinicians and staff and Emory Healthcare and Emory University public safety and police officers.

To date, Giordano and his Emory nursing, medicine, public health, and spiritual health colleagues have trained more than 250 frontline workers.

Once a week, wellness workshops are held in departments and units within the hospitals. Those wanting to learn more may take an eight-hour program grounded in spiritual health that combines classroom instruction and contemplative exercises.

Some participants have become certified trainers themselves, a development that will have a sustainable effect on worker well-being.

Grady is a prime example. When a newly certified instructor there held a workshop, more than 70 people attended. Grady now has 10 certified trainers. Mindfulness and self-compassion skills are now taught to Grady nurses during orientation and to a unit incident response team, says Michelle Wallace, DNP, RN, FRCN, NEA-BC, FACHE, chief nursing officer at Grady Health System.

Online mindfulness instruction will soon be available through the Emory Nursing Experience, which provides continuing education for nurses. — Pam Auchmutey

Beth Ann Swan leads ARCHWAy, which will train 450 community health workers from five Atlanta-area counties.

Beth Ann Swan leads ARCHWAy, which will train 450 community health workers from five Atlanta-area counties.

Supporting the community health workforce

Faculty member: Beth Ann Swan, PhD, RN, FAAN, associate dean and vice president for academic clinical partnerships and Charles F. and Peggy Evans Endowed Distinguished Professor in Simulation and Innovation

Partners/Community: AID Atlanta, Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition, Boat People SOS, Four Corners Primary Care Centers, Emory Hillandale Hospital, Fulton County Board of Health, Fulton County Jail, Georgia Department of Public Health, Latino Community Fund Georgia, and other community organizations

Community health workers often have different job titles: community health advisor, outreach worker, patient navigator, peer counselor, and promotore de salud. The School of Nursing will lead a training program to expand this workforce to serve vulnerable individuals in five Atlanta-area counties.

During COVID-19, community health workers played a vital role in vaccine outreach and building vaccine confidence. These workers, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services officials note, are trusted voices in their communities. They help their neighbors stay healthy by connecting them to well-child care, chronic disease care, mental health and substance use prevention and treatment, and other vital services.

Numbers show that Atlanta needs more of these workers. In a recent ranking of the nation’s top 20 cities, Atlanta ranked next to last in health care cost, quality, and access.

The School of Nursing aims to improve this through the Atlanta Region Community Health Workforce Advancement (ARCHWAy) Program. Through this program, the school will provide 12 weeks of training for new and existing community health workers serving vulnerable populations in Clayton, Coweta, DeKalb, Fulton, and Gwinnett counties. The program will also assist trainees with stipends, field and job placements, support services, referrals, financial literacy support, and mentoring.

Classes will be taught online and onsite at the Emory Nursing Learning Center in Decatur, utilizing simulated experiences and hands-on learning.

Over the next three years, faculty from the School of Nursing will lead 11 cohorts to train 450 community health workers.

ARCHWAy is funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration. Emory is the only nursing school in Georgia and one of three in the nation to receive funding for this type of program. — Pam Auchmutey

Preventing acute kidney injury in Florida farmworkers

Faculty members: Linda McCauley 79MN, PhD, RN, FAAN, FRCN, dean of the School of Nursing; Vicki Hertzberg, PhD, FASA, professor; and Roxana Chicas 16BSN 20PhD, assistant research professor

Partners/Community: The Farmworker Association of Florida and the Southeastern Coastal Center for Agricultural Health and Safety

Harvesting crops, flowers, and greenery is grueling work — one that can lead to heat-related illnesses, according to a study led by the School of Nursing. Equipped with this information, Florida farmworker leaders are working to advocate for better working conditions for workers.

During summers in Central Florida, daily temperatures typically rise into the 90s. For migrant farmworkers working for area fern growers, the heat is more than uncomfortable. It can lead to acute kidney injury (AKI), according to the School of Nursing’s recent Occupational Health Exposure and Renal Dysfunction (OHEaRD) study.

Heat-related kidney damage among workers is caused by different factors. The material used to deflect sunlight off fern beds tends to keep heat in, causing farmworkers’ body temperatures to rise to the fever threshold of 100.4 degrees. Workers often don’t drink enough water to maintain a normal temperature and hydration.

How farmworkers are paid is also a factor, the study found. Workers who are paid by the hour take water and meal breaks and experience lower rates of kidney illness. Workers paid by the piece — the number of ferns they pick — often skip water breaks. They push their bodies harder, leading to a higher incidence of AKI as well as rapid heart rate and nausea.

The AKI findings are based on a 32-month study that followed 115 agricultural workers in two Florida communities.

Going forward, OHEaRD results will help the Farmworker Association of Florida’s efforts to persuade growers and policymakers to continue to improve working conditions for these workers, who have the highest heat-related mortality of all occupation groups in the United States.

OHEaRD is funded by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Researchers from Emory’s School of Medicine and Rollins School of Public Health are collaborators. — Pam Auchmutey

OHEaRD study collaborators include Jasmin Avila (left) and Nezahualcoyotl Xiuhtecutli (right) of the Farmworker Association of Florida and Roxana Chicas (second from left) and Silvia Vega (second from right) of the School of Nursing.

OHEaRD study collaborators include Jasmin Avila (left) and Nezahualcoyotl Xiuhtecutli (right) of the Farmworker Association of Florida and Roxana Chicas (second from left) and Silvia Vega (second from right) of the School of Nursing.

Abby Mutic (center) discusses soil health with clinicians and staff at the Center for Black Women's Wellness in Atlanta.

Abby Mutic (center) discusses soil health with clinicians and staff at the Center for Black Women's Wellness in Atlanta.

Equipping Black women to avoid toxic environmental exposures

Faculty member: Abby Mutic 19PhD, CNM

Partners/Community: The Center for Black Women’s Wellness and the Region 4 Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit (PEHSU), a network of reproductive and children’s environmental health experts

Through Prescriptions for Preventions, a partnership with the Center for Black Women’s Wellness in Atlanta, Black mothers will have a much-needed resource to address environmental health risks in and around their homes.

As a young, certified nurse-midwife caring for pregnant women in rural Missouri, Abby Mutic was struck by how many of them experienced environmental stressors. They wondered if exposures at work or home were affecting their health and threatening the health of their families and unborn babies.

To find more answers, Mutic entered the PhD program at Emory’s School of Nursing, where she studied prenatal exposure to flame retardant materials. Now an assistant professor, Mutic continues to focus on environmental impacts on health, especially in children of color.

Mutic enjoys a moment with Center for Black Women’s Wellness staff members at their office.

Mutic enjoys a moment with Center for Black Women’s Wellness staff members at their office.

Through research, community presentations, and health fair screenings, Mutic strives to identify the people most affected by harmful environmental exposures and help them address their concerns. She is partnering with Atlanta’s Center for Black Women’s Wellness (CBWW) on a program called Prescriptions for Prevention (RxP), which is set to roll out this year.

RxP will employ an environmental health screener to work with CBWW patients and families, sharing guidance from the Region 4 PEHSU in culturally relevant ways. During clinic visits, the screener will evaluate exposure risks and factors that may protect against risk or increase risk of poor health.

Reports of exposures or environmental concerns will automatically generate a flag in the electronic medical record, alerting health care providers to address and possibly investigate further. The “prescription” they give to clients will consist of information on how to find and use available resources to reduce exposure. — Sylvia Wrobel

Strengthening culturally sensitive acute care

Faculty members: Roxana Chicas 16BSN 20PhD, assistant research professor, and Carrie McDermott, PhD, APRN, ACNS-BC, assistant professor

Partners/Community: Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition, Boat People SOS, and Latino Community Fund Georgia

The School of Nursing has integrated the social determinants (SDOH) of health into its courses. The next step is to teach students how to address these factors in clinical practice. The place to begin: hands-on learning in the school’s clinical skills and simulation labs and working with community partners.

Nurses today must know how to deliver high-quality patient care within the context of a patient’s cultural, ethnic, racial, and gender identity.

A new program, Toward Health Equity and Literacy: Training for Optimal RN Efficacy in Acute Care (2HEAL), will ensure that Emory undergraduate nursing students are prepared to address these factors.

2HEAL will expand how students address SDOH in clinical training and deepen their insight into health equity and health literacy for underserved populations in metro Atlanta.

Beginning this fall, BSN students will take part in simulations with manikins and standardized patients at the Emory Nursing Learning Center. They will also learn about SDOH by interacting with three community partners: Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition, Boat People SOS, and Latino Community Fund Georgia. Through these partnerships, students will see how SDOH affect diverse populations and how community organizations improve health literacy and equity.

The faculty leading 2HEAL will also create web-based learning modules for clinical instructors and preceptors through the Emory Nursing Experience continuing education program.

2Heal is funded by a grant from the Health Services and Resources Administration. — Pam Auchmutey

Expanding mobile health in Atlanta and rural Georgia

Faculty member: Quyen Phan 03MSN, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, assistant clinical professor

Partners/Community: Georgia Ellenton Farmworker Health Clinic, Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition, Boat People SOS, and Atlanta’s Mexican Consulate

For many people, access to health care is minimal or nonexistent. Emory In MOTION will help change that by providing mobile health services in nine Georgia counties. Mobile health units will be equipped to provide nurse-led health care in partnership with community agencies. Emory nursing students will also benefit as they learn to provide culturally sensitive clinical care.

On Wednesdays, the Atlanta Harm Reduction Coalition (AHRC) mobile van heads to a public park, a store parking lot, or another location to provide needle exchanges, Narcan, fentanyl test kits, health education, and HIV and hepatitis C testing.

Along for the ride is a nurse-led team of Emory BSN students who provide health screenings, health care, wound care, and telehealth services for the people served by AHRC, an organization that works to reduce the impact of substance use, HIV/AIDS, and other conditions.

The students are among the first to participate in Emory In MOTION, a mobile health training program funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The project will help expand health care access and culturally aligned care in Atlanta and rural Georgia and provide learning opportunities for pre- and post-licensure students.

In South Georgia, Emory In MOTION is working with the Georgia Ellenton Farmworker Health Clinic, a longtime School of Nursing partner near Moultrie, to purchase and staff a nurse-led mobile van that operates year-round. The van will also provide services at the school’s successful Farmworker Family Health Program, offered two weeks every summer. A nurse practitioner, supported by HRSA funding, will oversee the expanded mobile health services and precept Emory nursing students.

In Atlanta, a new family nurse practitioner will oversee students and expand mobile health services for AHRC. Another family nurse practitioner will guide students on a mobile health team with Boat People SOS. Nurse practitioners and students will work with the Mexican Consulate to provide mobile health care for the area’s Hispanic population.

One of the largest Health Resources and Services Administration grants in the history of the school, Emory in Motion also includes funding to support 10 mobile health student scholars annually. — Pam Auchmutey

Helping African American mothers avoid prenatal and postpartum complications

Faculty member: Alexis Dunn Amore, PhD, CNM, FACNM, FAAN, assistant professor

Partners/Community: Nurse-midwives and other clinicians, the Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Coalition of Georgia, and other pregnancy-related organizations

Not recognizing the severity of physical or emotional symptoms during or after pregnancy can be life-threatening. MAMA LOVE gives African American mothers a tool to prevent that.

Early in 2023, the web-based program MAMA LOVE went live. Pregnant women now have a free, accessible, and user-friendly tool to determine the urgency of any symptoms and what they should do and when.

Founder and director Alexis Dunn Amore is an assistant professor in the School of Nursing and a certified nurse-midwife whose work focuses on high-risk pregnancies in communities of color.

Many of her patients, with few other resources at their disposal, often turn to Google or a friend to ask for advice about symptoms. Should I be worried? Call someone? Wait? For symptoms suggesting life-threatening conditions like sepsis, eclampsia, cardiomyopathy, or acute postpartum depression, even a short delay in intervention can be deadly. Amore decided to build a site where women could quickly and easily find information.

When entering the site, 10 boxes pop up with symptoms such as breathlessness, blurred vision, chest pain, thoughts of harming oneself, and not wanting to touch the baby. If the woman acknowledges any of these symptoms, the site tells them to go to the ER or call 911.

If none apply, the pregnant person can select physical, mental, or social factors they are experiencing, and the program assigns them color-coded advice.

RED indicates symptoms that need immediate emergency follow-up.

YELLOW assures the woman that a symptom needs follow-up with a provider.

BLUE advises the woman to call a clinic or nurse helpline to get more information.

The website also includes links to helplines and other resources.

MAMA LOVE is a community effort, says Amore, built with guidance from local doulas, OB-GYNs, nurse-midwives, patients, community organizations, and focus groups. Amore and nurse-midwife and doctoral student Abby Britt 13MSN, CNM, FACNM, MA, met regularly with experts in the APP Hatchery, part of the Georgia Clinical & Translational Science Alliance. The American College of Nurse Midwives helped with the rollout, and the Robert W. Woodruff Fund supported the project. — Sylvia Wrobel

Alexis Dunn Amore (second from right) developed MAMA LOVE to support African American mothers.

Alexis Dunn Amore (second from right) developed MAMA LOVE to support African American mothers.