Changing the narrative

of your self

In a new book, a neuroscientist ponders storytelling and identity

Gregory Berns, Emory professor of psychology, keeps rewriting the narrative of his life. He earned a PhD in bioengineering, became a physician and then a practicing psychiatrist before changing his focus to computational neuroscience. His research using functional magnetic resonance imaging delved into everything from how the human brain decides whether to “sell out” to the effects on the brain of reading a novel.

For the past decade, he has focused on using fMRI to understand canine cognition. He was the first to train dogs to enter an fMRI machine and lie awake, unrestrained and perfectly still during scans. That work yielded glimpses of how man’s best friend processes smells, words, quantities of objects and food rewards versus praise.

"If you want to change your identity you must change the narrative," says Emory neuroscientist Gregory Berns. Partly spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, he's made another deep dive into his own sense of self.

"If you want to change your identity you must change the narrative," says Emory neuroscientist Gregory Berns. Partly spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, he's made another deep dive into his own sense of self.

He became a bestselling author with the publication of “How Dogs Love Us” in 2013. His other popular books include “What It’s Like to Be a Dog,” “Iconoclast: A Neuroscientist Reveals How to Think Differently” and “Satisfaction: Sensation Seeking, Novelty and the Science of Finding Fulfillment.”

Like many people during the COVID-19 pandemic, Berns took a long, hard look at his life and his work and decided to make some major changes. He moved with his family to a farm about an hour south of Atlanta, where he tends to three dogs, four chickens and a small herd of seven cattle.

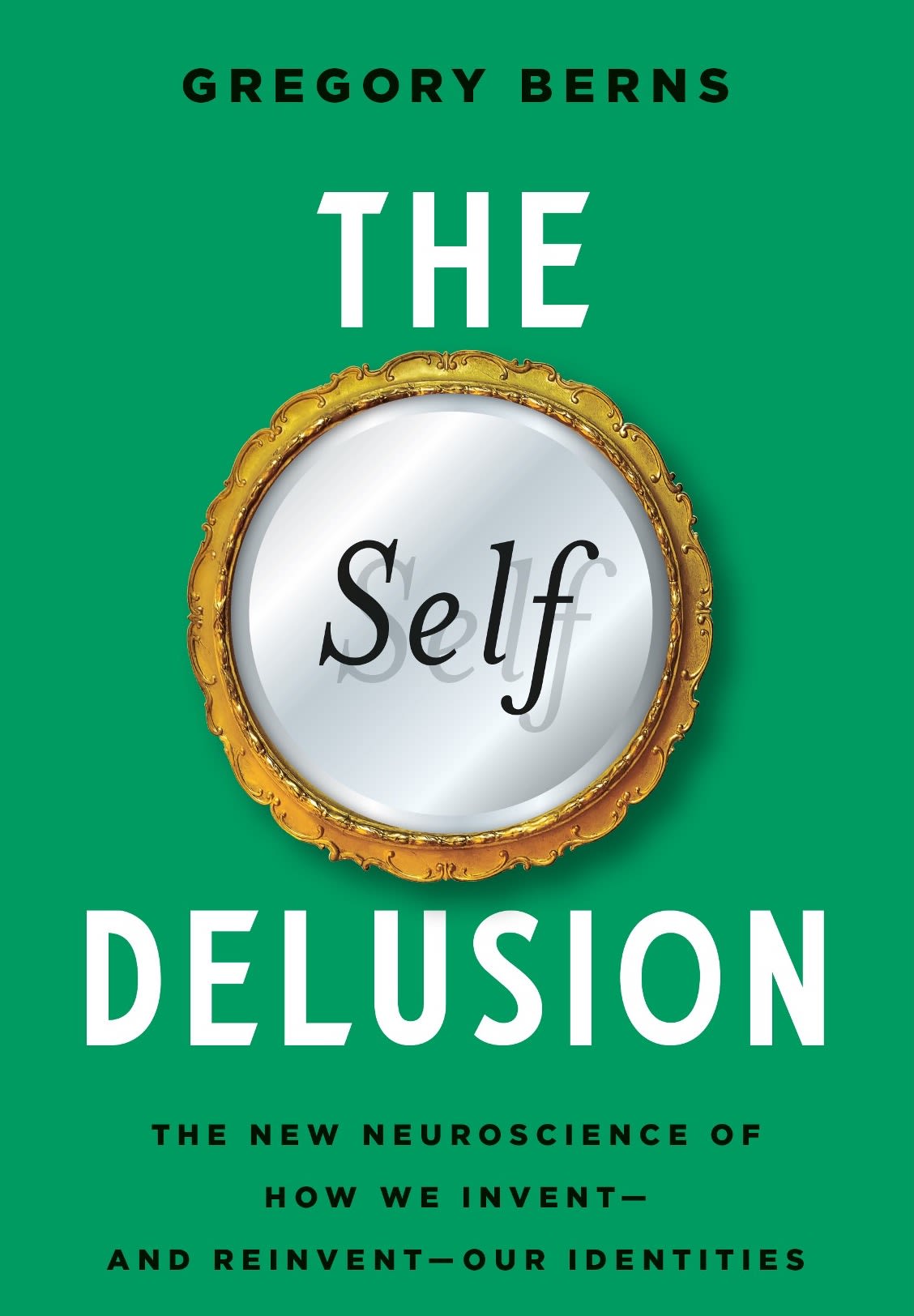

He also wrote another book, “The Self Delusion: The New Neuroscience of How We Invent — and Reinvent — Our Identities,” which will be published by Basic Books on Oct. 18. In the following Q&A he discusses the book and how it reflects the changing trajectory of his own life.

Why did you write this book?

I’ve always wanted to write about some of the research I did many years ago about how reading fiction changes the brain. The book became more about how narratives make us into who we are.

I can break down the question, “Who am I?” into a professor, a father, a farmer, but those are just labels. The parts alone do not constitute the self. Our identity is the story that we tell ourselves and other people about our lives. This narrative is the glue that binds together the things that happen to us and the things that we do.

What is the scientific evidence for this hypothesis?

The book pulls together some of the latest research into how the brain constructs memory and narrative. The brain is not a high-fidelity video recorder of everything that happens to us. Instead it captures snapshots, or a highlight reel, of our lives. The role of narrative is to fill in all the spaces in between to construct an identity that makes sense to us.

Some work done here at Emory shows how childhood memories form and the importance of family narratives in that process. There is evidence that children who hear a lot of detailed stories have richer memories of their childhoods. The implication is that the stories become part of them.

Not just family stories but fairy tales and other stories that we’ve heard provide a template for interpreting our lives that stays with us. The stories that you consume, even as adults, shape who you are and who you think that you are. I use the phrase, “You are what you eat.”

A caretaker of farm animals is part of Berns' new identity. Above he combs "Ricky Bobby," a miniature Zebu bull.

Can you change your identity by changing the narrative?

If you want to change your identity, you must change the narrative. Even though it’s difficult to do that, the realization that you can is the first step.

People sometimes have this feeling that they have always been the same core person, that the person they were as a child is just a younger version of themselves. But really the only basis for that feeling is the stories that you have in your head. On a physical level, there is no way you can say that you are the same because your body and your brain have changed so dramatically.

What advice do you have for people who want to change their personal narratives?

“The Self Delusion” is philosophical and is not a self-help book. But I do give some potential exercises that might start someone on the path to reinventing themselves.

One exercise is to think of yourself in the present and imagine that you have a clone of yourself with an exact replica of your brain with all your memories. You have two choices. You can stay in your current life, in which case you will be writing the story of your clone. Or your clone can take your place, and then you will be writing the story of yourself in a new life. Which one would you choose and why?

How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect the book and your identity?

The author that started writing this book in 2019 before the pandemic began is not the author that finished it this year.

COVID certainly changed everyone in some way. We had this major disruption in life. A lot of people died. Technology changed. I thought, “Do I want to go back to pick up the pieces in terms of my research and what I was doing? Or do I want to make a break with that version of me?”

I decided that I wanted to do something different. The world has changed. New interests and questions were tugging at me.

What is the new narrative of your life?

I moved to a farm and became immersed in issues surrounding the sustainability of modern life. The farm is 85 acres. About 20 acres are pasture and the rest is woodlands and wetlands. It’s a magical place, a miniature ecosystem with a bit of everything.

I started thinking that maybe I could do something to make the world a little better using my background in decision making and animal cognition. That’s all I can say right now because I’m still working on the narrative for a new version of myself.

Interview by Carol Clark

Related stories:

Decoding Canine Cognition through Machine Learning; A Novel Look at How Stories May Change the Brain; How Family Stories Help Children Weather Hard Times; Childhood Amnesia: The Age Our Earliest Memories Fade

Media contact: Carol Clark, carol.clark@emory.edu, 404-727-0501