Physicist

Seeks Ultimate

Formula for Fun

A quest for bigger,

better bubbles

By day, Justin Burton is an Emory associate professor of physics, conducting high-level research on fluid dynamics and granular materials. Evenings and weekends, however, he turns into a comic-book version of a scientist. Not a mad scientist, though. More like a glad scientist.

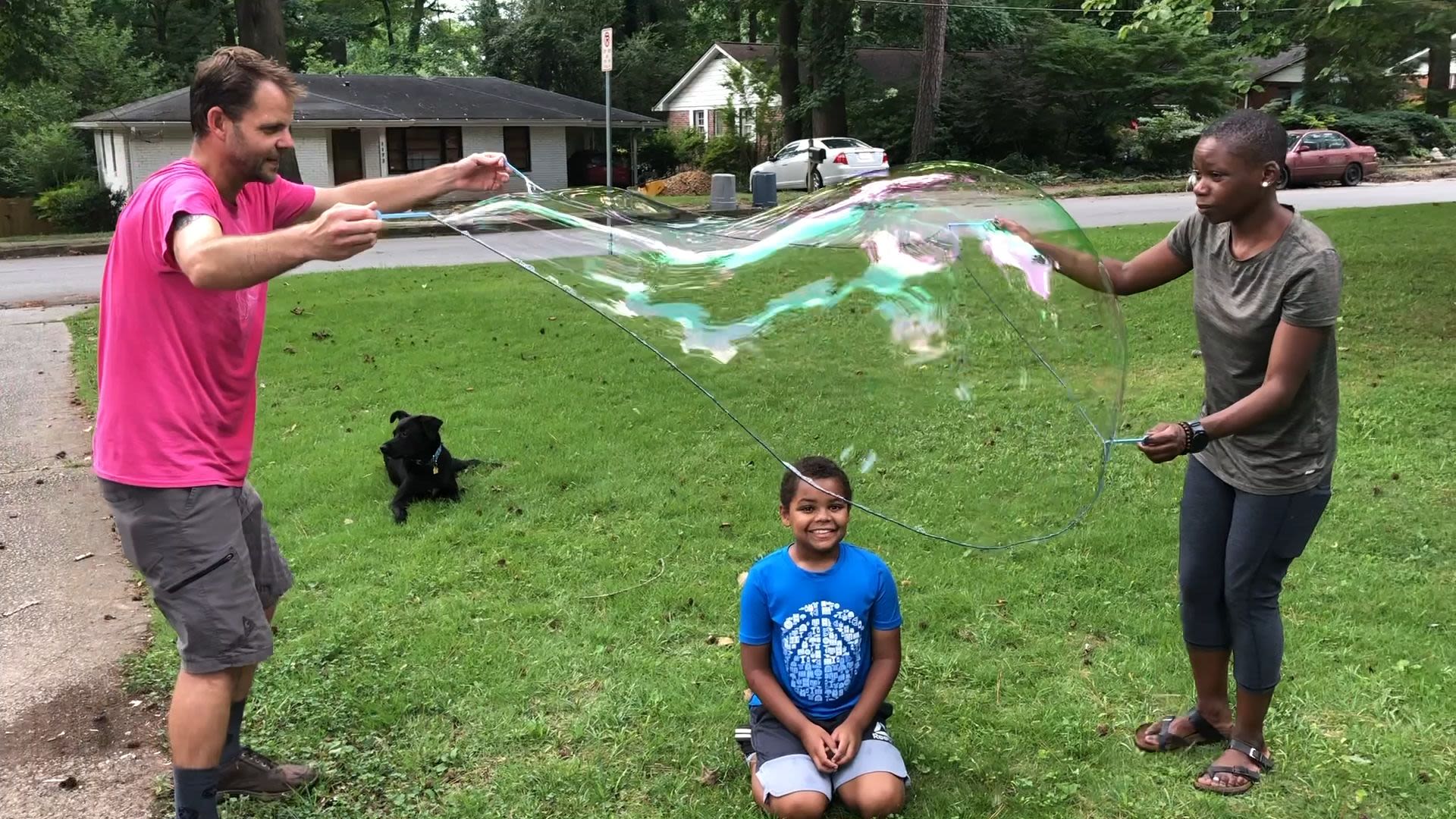

“They call him ‘Dr. Bubbles,’” says Jonah Burton, age 9, explaining his father’s alter ego as an enormous bubble floats past his head.

“That’s a big one! Can I pop it?” Jonah asks, as he dashes off to do so.

Jonah and his mom, Afeira, along with the family dog Boba Fetch, are braving gnats and the heat and humidity of a Georgia summer to assist Burton in an ever-expanding quest: Testing formulas and techniques to make the ultimate giant soap bubbles. They are using an Inormo “Family Bubble” string wand, a giant bubble-maker toy partly inspired by Burton’s research. (The couple’s 11-year-old daughter, Maia, and the family cat, Luna, preferred to stay inside with the air conditioning.)

Burton is experimenting by adding a squirt of soap scented with Meyer lemon to the bubble formula, a deviation from his usual mix.

Justin and Afeira Burton encase their son Jonah in a giant bubble while Boba Fetch looks on.

Justin and Afeira Burton encase their son Jonah in a giant bubble while Boba Fetch looks on.

“We had a birthday party for Jonah in May and we were out of Dawn dish soap,” Burton explains.

Dawn has long been considered a gold-standard ingredient for homemade formulas among leading giant-bubble enthusiasts. But with no Dawn available and young party guests arriving, Burton had to improvise. He grabbed some discount-store lemon-scented soap that the family happened to have on hand and mixed up some bubble juice.

“Amazingly, it worked even better than Dawn,” Burton recalls. “I don’t know why, but I think it may have something to do with the lemon. So I’m studying it more.”

Burton’s bubble quest began several years ago when he attended a conference in Barcelona and became mesmerized by street performers blowing giant soap bubbles. As a specialist in fluid dynamics, he marveled at the ability of the performers to create bubbles nearly as big as cars. They shimmered with an ever-changing array of colors. That rainbow effect shows that the film’s thickness is comparable to the wavelength of light, or just a few microns.

So how could such a microscopically thin film stretch over such a large distance before bursting? He began investigating the question in his lab.

That research led to the lab’s 2020 publication of a paper called “How to make a giant bubble” in the journal Physical Review Fluids. Emory graduate student Stephen Frazier was first author of the paper and has since graduated and gone to work in the solar energy field.

Watch a video to learn a formula for making giant soap bubbles tested by the Burton Lab.

The researcher’s laboratory tests revealed that polymers — substances made up of long chains of repeating molecules — are the key ingredient for colossal bubbles. Common polymers used in soap bubble recipes are natural guar, a powder used as an additive in some foods, and industrial polyethylene glycol, a lubricant used in some medicines. The long, fibrous strands of the polymers entangle and enable the bubbles to flow smoothly and stretch further without popping.

The paper blew up in the media, garnering worldwide publicity. In addition to fielding press interviews, Burton wrangled emails from bubble enthusiasts. Inventors wanted to float their ideas for bubble-making contraptions. Street performers inquired about soap formulas. A company that does light shows for landmark skyscrapers asked Burton to weigh in on the possibility of adding giant bubbles to these extravaganzas.

An attorney in Washington D.C. who advocates for children in the foster-care system also contacted Burton. The attorney, who has long had a fascination with giant bubbles, asked Burton for his input on a collection of bubble-making tools he was developing called Inormo.

Burton agreed to help with creating a tailor-made formula for the products. He also tested the prototype for the Inormo string wands, now on the market, with his family. In exchange, Burton gets a tiny percentage of Inormo’s sales.

“I don’t really expect to make any money from this,” Burton says. “I consider it a hobby that’s rewarding in other ways. It’s kind of like being part of Santa Claus’ workshop. I’ve helped create a toy that makes children happy.”

The fact that the toy doesn’t involve any electronics and gets kids playing outside is a bonus, Burton adds.

Even after the launch of Inormo, Burton’s bubble experiments continue in the family yard. Results vary, he notes, depending on atmospheric conditions such as temperature, wind and humidity.

The idea behind the Inormo “Family Bubble” string wand is that it makes a bubble big enough to envelop a child before it pops. It’s a bit tricky. It takes two adults to operate the bubble string and lots of trial and error. The most important factor may be a spirit of fun and wonder.

You couldn't ask for a more enthusiastic bubble-research assistant than Jonah Burton.

You couldn't ask for a more enthusiastic bubble-research assistant than Jonah Burton.

“Let’s try it again!” Jonah says, as a bubble pops after it touches his hair. “I’d like one to cover me all the way down to the ground!”

Jonah is considering a career in science, but not bubble science.

“I want to be an Oreo-ologist,” he says.

He explains that his father showed him a recent paper on Oreo cookie experiments conducted by mechanical engineers at MIT. A battery of tests led to the discovery of why the cream sticks to just one wafer when the cookie is twisted apart. It turns out that twisting an Oreo mimics a standard test in rheology, the study of how a non-Newtonian material flows when under stress.

Like the MIT Oreo-ologists, Burton enjoys inspiring a childlike curiosity in people of all ages. He was recently featured on the Tumble Science Podcast for Kids, answering young listeners’ questions about the science of bubbles, such as “Why do bubbles have shadows?”

“In a way, the bubble research is the most influential project ever done by my lab,” Burton says.

The discovery of the role that polymers play in giant bubbles may one day lead to methods to improve industrial processes such as the flow of oils through pipes. Or it may not, Burton concedes.

“Not every physics discovery has to transform industry or lead to an insight about black holes,” he says. “Sometimes a discovery just leads to joy and that’s okay too.”

Story and video by Carol Clark

Related links

Physics of Giant Bubbles, the Burton Lab,

Emory Department of Physics

Media Contact: Carol Clark, carol.clark@emory.edu, 404-727-0501