Into the

heart of

brightness

An ethnobotanist's

memoir celebrates

a life in science,

from her roots

to the fruits of her labor

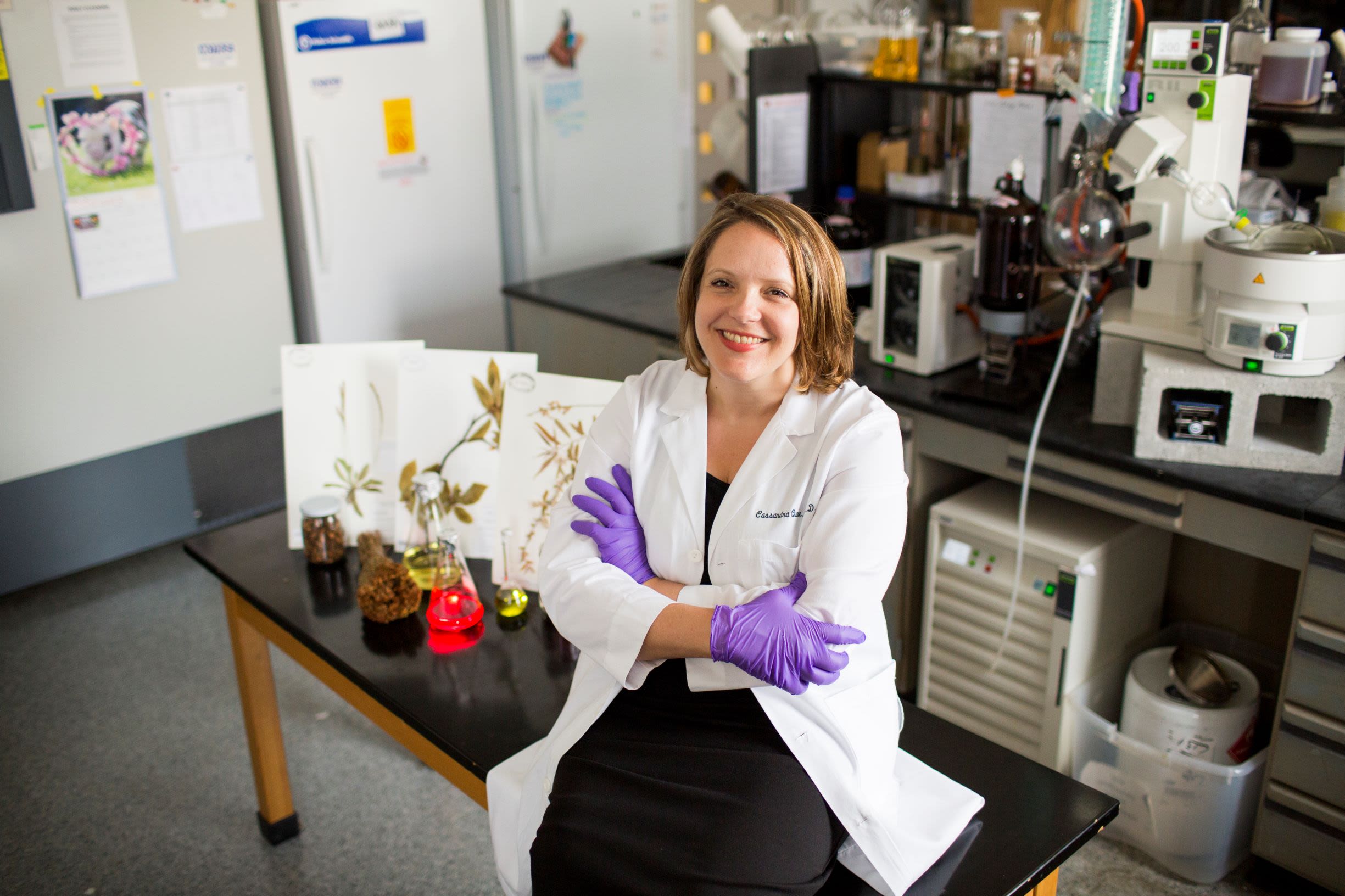

Cassandra Quave’s life is like a tropical forest: Varied, colorful, bursting with life and laced with hidden paths that must be constantly cleared to move along them. Her new memoir guides readers through a world of plants and the people entwined with them. The story is sometimes dark but mostly uplifting, lit up by her personal revelations and scientific discoveries.

“The Plant Hunter: A Scientist’s Quest for Nature’s Next Medicines,” published by Viking, hit bookshelves Oct. 19. A campus Q&A with the author will be held Tuesday, Oct. 26, at the Emory Student Center in Multipurpose Rooms 4-5-6, from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. Quave will be in conversation with journalist and author Maryn McKenna from Emory’s Center for the Study of Human Health.

Her story begins with a spirited childhood in rural Florida. It’s marked by dozens of surgeries and chronic pain, as well as her volunteer work in a hospital and joyful explorations of nature. It moves on to her pivotal years as an Emory undergrad, winds through the Amazon and little-known environments of the Balkans and Italy, graduate school, post-doctoral training, marriage and children. Quave is now back at Emory where she is curator of the Emory Herbarium and an associate professor at the Center for the Study of Human Health and the School of Medicine’s Department of Dermatology.

“I was inspired to write the book because people have found my work interesting,” says Quave (it rhymes with “wave”). “It’s a chance to tell the larger story of my life, bringing together all the different parts of it.”

As a medical ethnobotanist, Quave studies how people survive when they have few resources other than what is available to them in their immediate environment. She follows clues hidden in ancient plant remedies to search for new compounds to combat the modern-day scourge of antibiotic-resistant infections. She holds six patents, is a fellow of the Explorer’s Club, and a past president of the Society for Economic Botany.

"We have barely scratched the surface of the medicinal value of plants," Quave says.

"We have barely scratched the surface of the medicinal value of plants," Quave says.

Even at her home near Emory, Quave is immersed in plants. She wears a dress printed with lemons as she gives a tour of her terraced garden: Tomatoes, Hungarian peppers and okra grow amid chives, lemongrass and Thai holy basil.

Mint scents the air as she crushes peppermint leaves in her fingers and explains how they have soothed stomach aches for centuries. She points out motherwort (sipped in a tea to ease the anxiety of childbirth) and cone flowers (the roots are pounded into a tincture for cold symptoms).

She breaks off a sprig of celandine, a member of the poppy family, and a bright orange resin oozes out. “The resin is toxic in the wrong doses, but it’s also a traditional remedy applied to warts,” Quave says.

Quave scours historical documents and interviews traditional healers as a first step in her search for medically important plant compounds. Her discoveries that extracts from the berries of the Brazilian peppertree and the leaves of the European chestnut tree disarm dangerous antibiotic-resistant staph bacteria have been covered by major media around the globe.

She leads her visitor past her home office — a sunroom lush with philodendrons, parlor palms and hanging pots of ferns. She settles onto her living room sofa and stretches out her legs. One of them is made of metal. The artificial limb is encased in a colorful plastic cover, etched with sprigs of plants and scientific symbols.

Cassandra Quave tweeted the arrival of her newest artificial leg cover in this video. Follow her on Twitter @QuaveEthnobot. You can also find her on Instagram, Facebook (Dr. Cassandra Quave) and on her podcast, Foodie Pharmacology.

Cassandra Quave tweeted the arrival of her newest artificial leg cover in this video. Follow her on Twitter @QuaveEthnobot. You can also find her on Instagram, Facebook (Dr. Cassandra Quave) and on her podcast, Foodie Pharmacology.

“I got really tired of having a prosthetic covered in plastic skin,” Quave says. “When people see something fake that’s trying to look like a real leg it confuses them and they tend to stare more. I don’t like pretending to be something that I’m not.”

The ALLELES Design Studio creates a range of artistic covers that snap over metal prosthetics. “They removed the sense of shame about a prosthetic as something ugly that you have to hide,” Quave says. “They’ve flipped the narrative to celebrate it as something beautiful.”

A chance meeting with Quave led ALLELES designers to make a cover inspired by her science. Dubbed “The Plant Hunter,” it features key plants highlighted in her memoir. “It’s cool to have my prosthetic become more of a conversation starter about my life and my work instead of a distraction from it,” she says.

One goal of her memoir, she adds, is to provide the kind of role model she herself lacked. “A lot of amputee kids may want to become a scientist or an explorer or an adventurer,” Quave says. “I write about disability from a really honest perspective — the chronic pain and the challenges but also learning how to assess a problem and remove hurdles, whatever your limitations.”

Quave has been removing hurdles since she was born in the small town of Arcadia, in rural South Florida.

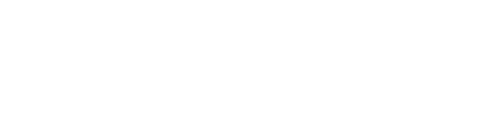

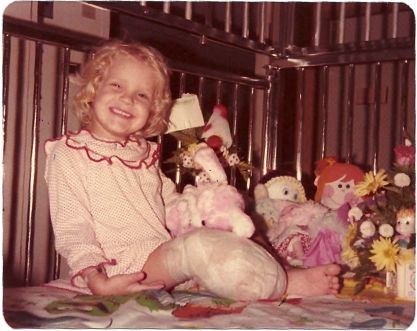

Quave as a toddler in the hospital, recovering from the amputation of her lower right leg.

Quave as a toddler in the hospital, recovering from the amputation of her lower right leg.

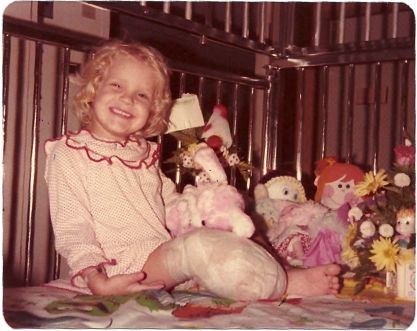

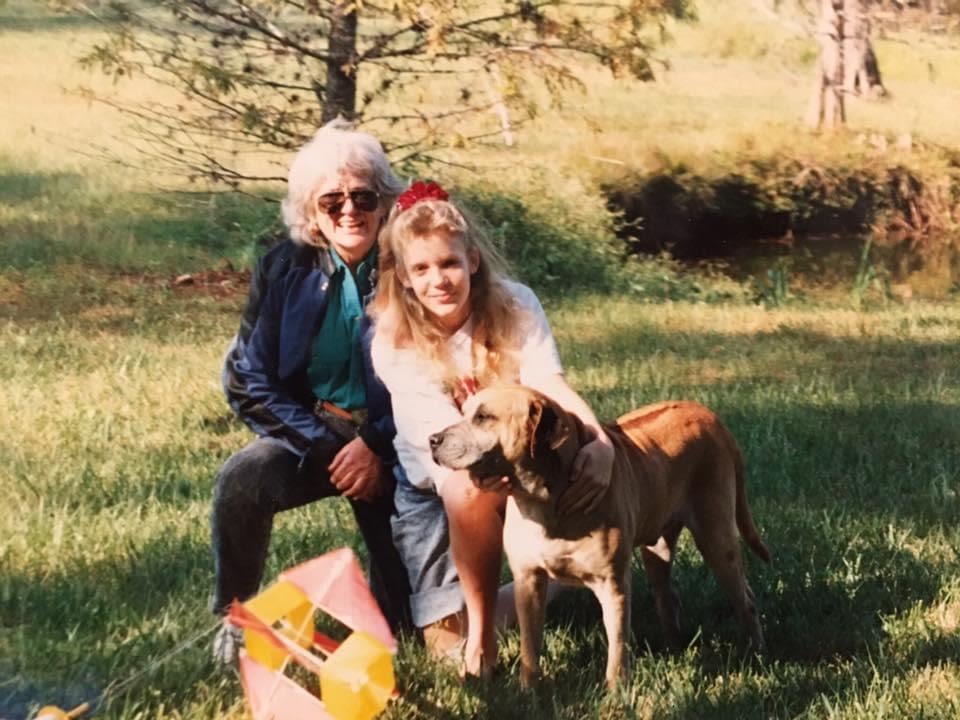

Quave with her grandmother and dog, Spot, at home in Florida in 1988.

Quave with her grandmother and dog, Spot, at home in Florida in 1988.

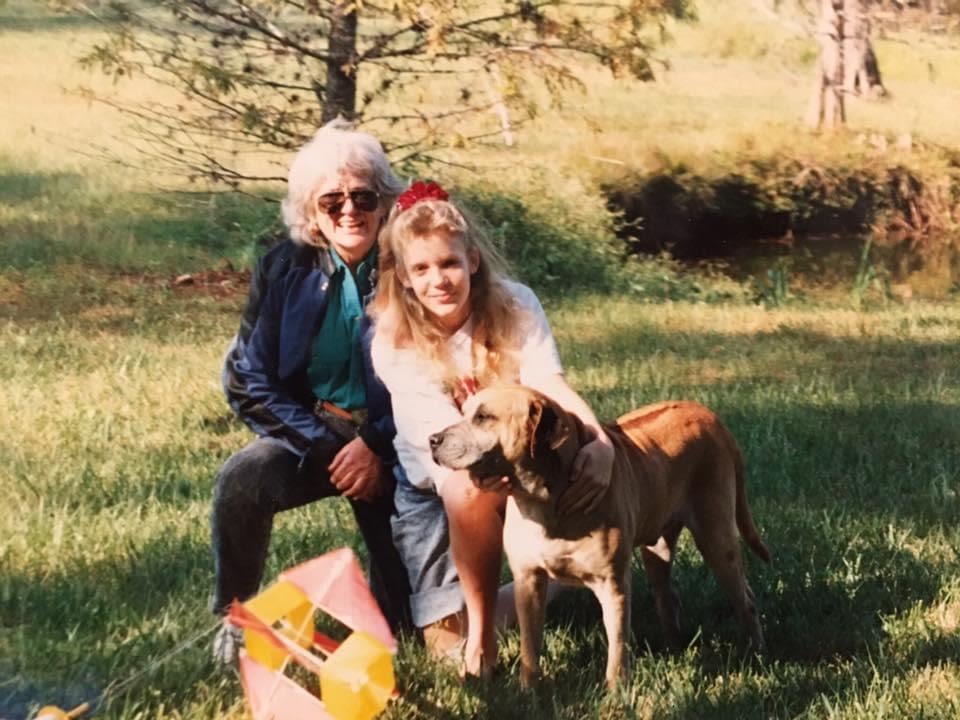

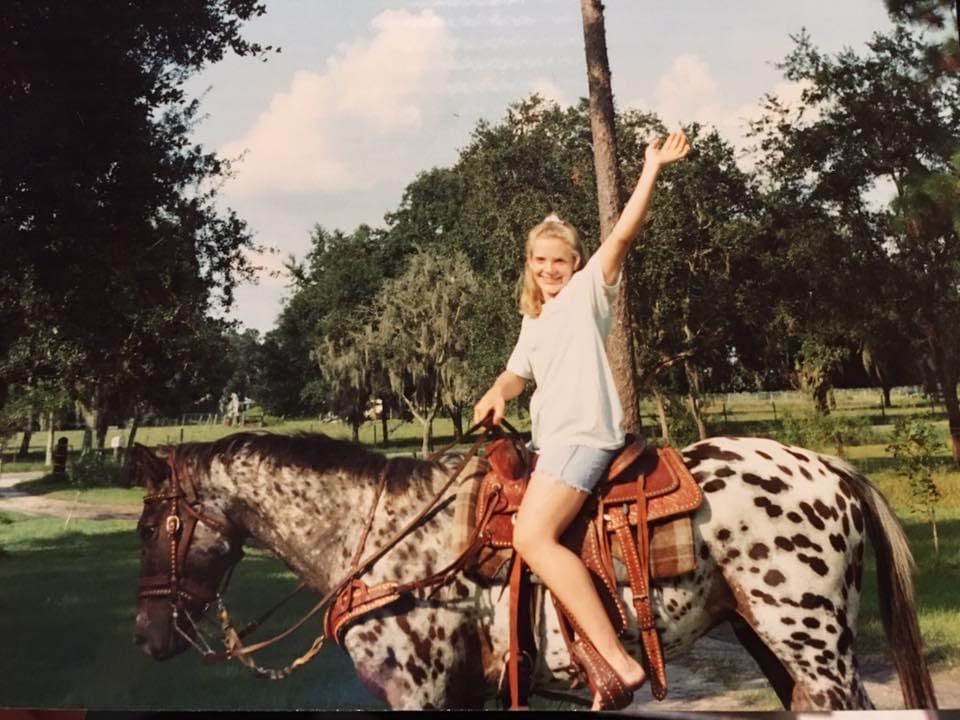

Riding her horse, Sequoia, in Arcadia, Florida, in 1993.

Riding her horse, Sequoia, in Arcadia, Florida, in 1993.

Her grandfather, father and uncles worked as land clearers, known as “stumpers.” When colossal longleaf pines in the South were felled for timber to build homes, they used bulldozers to push the remaining stumps out of the ground. They then blew them up with dynamite for grinding at a stump mill to extract turpentine and other byproducts.

The difficult work was an essential part of creating arable land for agricultural use, Quave explains.

At the age of 20, in 1969, her father joined the U.S. Army’s First Infantry Division. He was sent to Vietnam, where he trudged over landscapes recently defoliated by dioxin. Also known as Agent Orange, dioxin is a powerful herbicide that the U.S. military sprayed to eliminate forest cover while fighting the Vietcong.

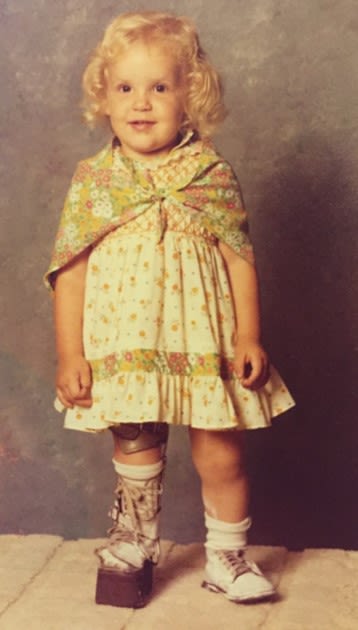

Her father’s exposure to the herbicide may have led to Quave’s multiple skeletal birth defects, including the absence of part of her right calf bone, she writes in her memoir.

When she was three, her right leg was amputated below the knee in an effort to improve her mobility. That surgery led to a life-threatening staph infection in the toddler. Her leg had to be cut off even shorter, leaving her with a heavily scarred stump that lacks fatty tissue, making prosthetics less comfortable.

"I'm so glad my parents had the strength not to help me do everything," Quave says. "That made me independent. It takes a special person to raise a disabled child."

"I'm so glad my parents had the strength not to help me do everything," Quave says. "That made me independent. It takes a special person to raise a disabled child."

Despite this rough start, Quave thrived. She and her younger sister loved running wild in their natural surroundings. “Florida is an amazing place,” she says, “and I was raised to have a strong connection to the land.”

Her father tacked boards to the trunk of a centuries-old live oak in their back yard so she could climb up it to read, reflect and observe the life forms proliferating on the tree. Tiny orchids sprouted from the bark and the delicate green fronds of resurrection ferns curled around branches bearded in Spanish moss.

In elementary school she began developing award-winning science fair projects — such as putting a drop of pond water beneath a microscope and drawing the creatures she saw living in it. Meanwhile, dozens of surgeries — including the need to correct her hip dysplasia and scoliosis of her spine — sparked Quave’s interest in medicine. She began volunteering at a local hospital while still in her teens, working directly with patients as well as in the lab.

She planned to become a doctor and follow in the footsteps of her pediatric orthopedist, Chad Price, who also happens to be an Emory alum.

As an Emory undergraduate, however, majoring in biology and anthropology, new paths beckoned to Quave.

As an Emory undergraduate, Quave did research in the Peruvian Amazon. Here she holds a baby sloth, a common pet for children there.

As an Emory undergraduate, Quave did research in the Peruvian Amazon. Here she holds a baby sloth, a common pet for children there.

A traditional Peruvian healer shares his knowledge with Quave.

A traditional Peruvian healer shares his knowledge with Quave.

Traveling by boat through the Amazon.

Traveling by boat through the Amazon.

In a class taught by Peter Brown, professor of anthropology, she learned that in some cultures, disabled people are venerated and believed to have special powers. In others, however, they have been left to die.

“It made me realize how fortunate I am to have been born in a country with access to health care,” Quave says. “I wondered what would have happened if I had been a child in a village without running water and electricity. I wouldn’t have been able to walk. What would my life been like?”

In a seminar taught by professor Michelle Lampl, now director of the Emory Center for the Study of Human Health, she discovered her love for research. “She challenged us to look at primary literature and dissect those papers,” Quave says. “I learned how to evaluate evidence.”

Larry Wilson, an instructor in the Department of Environmental Sciences, sparked her interest in tropical ecology and ethnobotany. Wilson organized an annual student trip to the Peruvian Amazon and Quave was determined to go even though she couldn’t afford it. Wilson helped her find a way, arranging for a student work-study project at the site.

Curandero Don Antonio Montero Pisco holds a shakapa bundle used in ceremonial rituals in the Peruvian Amazon.

Curandero Don Antonio Montero Pisco holds a shakapa bundle used in ceremonial rituals in the Peruvian Amazon.

An Amazon traditional healer named Don Antonio took the young Quave under his wing. “He held a rich knowledge of the medicinal properties of plants that he shared with me,” she says, “from the use of the latex from fig trees to treat intestinal parasites to the red resin of the dragon’s blood tree to treat wounds and diarrhea.”

Quave investigated how reliance on modern medicine caused local healers to stop passing on some helpful traditional practices, leaving a chasm when the stocks of modern medicines ran out. “Ideally we should combine the best of both modern and traditional medicine,” she says. “Some of the best modern-day drugs, including those for cancer and pain, have been derived from plants.”

Months later, Quave opened up her long-awaited acceptance letter from a medical school. “I realized that instead of practicing medicine as a physician, I wanted to discover and develop new medicines inspired by nature,” she says. “I found the courage to crumple that letter in my hand and took another, less-traveled path.”

The path has not been easy, although Quave often makes it seem that way.

"It's important to recognize individual organisms in your environment so you can build a relationship with them," Quave says.

While doing field work in Southern Italy she met her match in Marco Caputo, a native of the small town of Ginestra. Like Quave, Caputo spent much of his childhood outdoors, exploring a rural landscape of creeks, waterfalls and fields full of fragrant, yellow Ginestra flowers. In her book, Quave describes their storybook courtship, including a balcony scene, and their wedding in a 13th-century castle.

The couple now have four children: Trevor (17), Donato (16), Issabella (14) and Giacamo (8).

During a 2006 trip to Italy for fieldwork, Quave holds her son Donato. Her children often accompany her in the field.

During a 2006 trip to Italy for fieldwork, Quave holds her son Donato. Her children often accompany her in the field.

After graduate school and a post-doctoral fellowship, Quave came full circle when she returned to Emory in 2011, initially as a post-doc and then as a faculty member in 2013. Her lab draws on the myriad resources spanning the university, including the Center for the Study of Human Health, the Antibiotic Resistance Center, the School of Medicine, Rollins School of Public Health, the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, and the social and physical sciences in Emory College.

“I relished the chance to return to a broad, liberal arts university with a strong medical and public health component,” Quave says. “I love talking daily to leading scholars from different fields and being close to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.”

The caliber of Emory undergraduates was another draw. More than 100 undergraduates have trained in her lab, which has published more than 100 articles — many of them written by undergraduates.

"I relished the chance to return to a broad, liberal arts university with a strong medical and public health component," Quave says.

Quave is thrilled by the career successes of former lab members — from jobs in medicine to pharmacology research to biotech startups. But she’s also committed to cultivating her students’ awareness and appreciation of plants.

“I try to give my students the tools to make more informed decisions about how they live their lives,” Quave says. “Their choices affect both their own health as well as that of the planet.”

In her Food, Health and Society class, Quave invites students to scratch an orange rind with their fingernails and describe the sensory experience as the scent of citrus oil is released. She also holds classes in Lullwater Preserve, asking students to take photographs and write poems about what they observe.

Quave, bottom left, introduced her students to a Florida ecosystem during a 2016 field trip.

Quave, bottom left, introduced her students to a Florida ecosystem during a 2016 field trip.

The green blur of the natural world becomes something much more detailed and interesting when you stop to take a deeper look. “It’s important to recognize individual organisms in your environment so that you can start to build a relationship with them,” Quave says. “Then it’s no longer just a sea of strangers that you don’t care about.”

Many people have forgotten that they are also part of nature, she says. They don’t understand how the loss of biodiversity may impact humanity, including the rising risks for emerging infectious diseases, along with a decrease in the potential treatments for them.

“We have barely scratched the surface of the medicinal value of plants,” she says, “and yet two in five plants are currently estimated to be threatened with extinction due to the destruction of the natural world.”

For more information, please visit:

Cassandra Quave's author page, the Quave Lab, Emory Center for the Study of Human Health, Emory School of Medicine

Media inquiries: Carol Clark, carol.clark@emory.edu, 404-727-0501