Emora, a chatbot who cares for you

Emory students advance artificial intelligence with a bot that aims to serve humanity

A team of six Emory computer science students are helping to usher in a new era in artificial intelligence. They’ve developed a chatbot capable of making logical inferences that aims to hold deeper, more nuanced conversations with humans than have previously been possible. They’ve christened their chatbot “Emora,” because it sounds like a feminine version of “Emory” and is similar to a Hebrew word for an eloquent sage.

The team is now refining their new approach to conversational AI — a logic-based framework for dialogue management that can be scaled to conduct real-life conversations. Their longer-term goal is to use Emora to assist first-year college students, helping them to navigate a new way of life, deal with day-to-day issues and guide them to proper human contacts and other resources when needed.

Eventually, they hope to further refine their chatbot — developed during the era of COVID-19 with the philosophy “Emora cares for you” — to assist people dealing with social isolation and other issues, including anxiety and depression.

The team is led by faculty advisor Jinho Choi (center) and graduate students James Finch (left) and Sarah Finch.

The team is led by faculty advisor Jinho Choi (center) and graduate students James Finch (left) and Sarah Finch.

The Emory team is headed by graduate students Sarah Finch and James Finch, along with faculty advisor Jinho Choi, associate professor in the Department of Computer Sciences. The team also includes graduate student Han He and undergraduates Sophy Huang, Daniil Huryn and Mack Hutsell. All the students are members of Choi’s Natural Language Processing Research Laboratory.

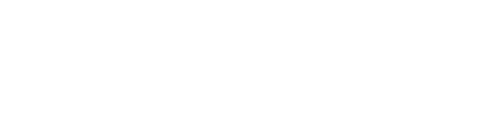

“We’re taking advantage of established technology while introducing a new approach in how we combine and execute dialogue management so a computer can make logical inferences while conversing with a human,” Sarah Finch says.

“We believe that Emora represents a groundbreaking moment for conversational artificial intelligence,” Choi adds. “The experience that users have with our chatbot will be largely different than chatbots based on traditional, state-machine approaches to AI.”

“If we can create more flexible and robust dialogue capability in machines, everyone would be on a more equal footing because using technology would become easier," says Sarah Finch, a graduate student in computer science.

“If we can create more flexible and robust dialogue capability in machines, everyone would be on a more equal footing because using technology would become easier," says Sarah Finch, a graduate student in computer science.

Last year, Choi and Sarah and James Finch headed a team of 14 Emory students that took first place in Amazon’s Alexa Prize Socialbot Grand Challenge, winning $500,000 for their Emora chatbot. The annual Alexa Prize challenges university students to make breakthroughs in the design of chatbots, also known as socialbots — software apps that simplify interactions between humans and computers by allowing them to talk with one another.

This year, they developed a completely new version of Emora with the new team of six students.

They made the bold decision to start from scratch, instead of building on the state-machine platform they developed in 2020 for Emora. “We realized there was an upper limit to how far we could push the quality of the system we developed last year,” Sarah Finch says. “We wanted to do something much more advanced, with the potential to transform the field of artificial intelligence.”

They based the current Emora on three types of frameworks to advance core natural language processing technology, computational symbolic structures and probabilistic reasoning for dialogue management.

They worked around the clock, making it into the Alexa Prize finals in June. They did not complete most of the new system, however, until just a few days before they had to submit Emora to the judges for the final round of the competition.

That gave the team no time to make finishing touches to the new system, work out the bugs, and flesh out the range of topics that it could deeply engage in with a human. While they did not win this year's Alexa Prize, the strategy led them to develop a system that holds more potential to open new doors of possibilities for AI.

“Doing this kind of dialogue research is our dream and we’re living it," says James Finch, a graduate student of computer science. "We are making something new that will hopefully be useful to the world.”

“Doing this kind of dialogue research is our dream and we’re living it," says James Finch, a graduate student of computer science. "We are making something new that will hopefully be useful to the world.”

In the run-up to the finals, users of Amazon’s virtual assistant, known as Alexa, volunteered to test out the competing chatbots, which were not identified by their names or universities. A chatbot’s success was gauged by user ratings.

“The competition is extremely valuable because it gave us access to a high volume of people talking to our bot from all over the world,” James Finch says. “When we wanted to try something new, we didn’t have to wait long to see whether it worked. We immediately got this deluge of feedback so that we could make any needed adjustments. One of the biggest things we learned is that what people really want to talk about is their personal experiences. ”

Sarah and James Finch, who married in 2019, are the ultimate computer power couple. They met at age 13 in a math class in their hometown of Grand Blanc, Michigan. They were dating by high school, bonding over a shared love of computer programming. As undergraduates at Michigan State University, they worked together on a joint passion for programming computers to speak more naturally with humans.

“If we can create more flexible and robust dialogue capability in machines,” Sarah Finch explains, “a more natural, conversational interface could replace pointing, clicking and hours of learning a new software interface. Everyone would be on a more equal footing because using technology would become easier.”

She hopes to pursue a career in enhancing computer dialogue capabilities with private industry after receiving her PhD.

James Finch is most passionate about the intellectual aspects of solving problems and is leaning towards a career in academia after receiving his PhD.

The Alexa Prize deadlines required the couple to work many 60-hour-plus weeks on developing Emora’s framework, but they didn’t consider it a grind. “I’ve enjoyed every day,” James Finch says. “Doing this kind of dialogue research is our dream and we’re living it. We are making something new that will hopefully be useful to the world.”

They chose to come to Emory for graduate school because of Choi, an expert in natural language processing, and Eugene Agichtein, professor in the Department of Computer Science and an expert in information retrieval.

“We believe that Emora represents a groundbreaking moment for conversational artificial intelligence,” says Jinho Choi, associate professor of computer science and the team's faculty advisor.

“We believe that Emora represents a groundbreaking moment for conversational artificial intelligence,” says Jinho Choi, associate professor of computer science and the team's faculty advisor.

Emora was designed not just to answer questions, but as a “social companion.”

A caring chatbot was an essential requirement for Choi. At the end of every team meeting, he asks one member to say something about how the others have inspired them. “When someone sees a bright side in us, and shares it with others, everyone sees that side and that makes it even brighter,” he says.

Choi’s enthusiasm is also infectious.

Growing up in Seoul, South Korea, he knew by the age of six that he wanted to design robots. “I remember telling my mom that I wanted to make a robot that would do homework for me so I could play outside all day,” he recalls. “It has been my dream ever since. I later realized that it was not the physical robot, but the intelligence behind the robot that really attracted me.”

The original Emora was built on a behavioral mathematical model similar to a flowchart and equipped with several natural language processing models. Depending on what people said to the chatbot, the machine made a choice about what path of a conversation to go down. While the system was good at chit chat, the longer a conversation went on, the more chances that the system would miss a social-linguistic nuance and the conversation would go off the rails, diverting from the logical thread.

“When you learn a foreign language, you get new insights into the role of grammar and word order,” Han He, a graduate student in computer science. “And those insights can help you to develop better algorithms and programs to teach computers how to understand language."

“When you learn a foreign language, you get new insights into the role of grammar and word order,” Han He, a graduate student in computer science. “And those insights can help you to develop better algorithms and programs to teach computers how to understand language."

This year, the Emory team designed Emora so that she could go beyond a script and make logical inferences. Rather than a flowchart, the new system breaks a conversation down into concepts and represents them using a symbolic graph. A logical inference engine allows Emora to connect the graph of an ongoing conversation into other symbolic graphs that represent a bank of knowledge and common sense. The longer the conversations continue, the more its ability to make logical inferences grows.

Sarah and James Finch worked on the engineering of the new Emora system, as well as designing logic structures and implementing related algorithms. Undergraduates Sophy Huang, Daniil Huryn and Mack Hutsell focused on developing dialogue content and conversational scripts for integrating within the chatbot. Graduate student Han He focused on structure parsing, including recent advances in the technology.

“A computer cannot deal with ambiguity, it can only deal with structure,” Han He explains. “Our parser turns the grammar of a sentence into a graph, a structure like a tree, that describes what a chatbot user is saying to the computer.”

He is passionate about language. Growing up in a small city in central China, he studied Japanese with the goal of becoming a linguist. His family was low income so he taught himself computer programming and picked up odd programmer jobs to help support himself. In college, he found a new passion in the field of natural language processing, or using computers to process human language.

His linguistic background enhances his technological expertise. “When you learn a foreign language, you get new insights into the role of grammar and word order,” He says. “And those insights can help you to develop better algorithms and programs to teach computers how to understand language. Unfortunately, many people working in natural language processing focus primarily on mathematics without realizing the importance of grammar."

After getting his masters at the University of Houston, He chose to come to Emory for a PhD to work with Choi, who also emphasizes linguistics in his approach to natural language processing. He hopes to make a career in using artificial intelligence as an educational tool that can help give low-income children an equal opportunity to learn.

“Thinking about how to turn metadata and numbers into something that sounds human is a lot of fun,” says Mack Hutsell, a senior majoring in English and computer science.

“Thinking about how to turn metadata and numbers into something that sounds human is a lot of fun,” says Mack Hutsell, a senior majoring in English and computer science.

A love of language also brought senior Mack Hutsell into the fold. A native of Houston, he came to Emory’s Oxford College to study English literature. His second love is computer programming and coding. When Hutsell discovered the digital humanities, using computational methods to study literary texts, he decided on a double major in English and computer science.

“I enjoy thinking about language, especially language in the context of computers,” he says.

Choi’s Natural Language Processing Lab and the Emora project was a natural fit for him.

Like the other undergraduates on the team, Hutsell did miscellaneous tasks for the project while also creating content that could be injected into Emora’s real-world knowledge graph. On the topic of movies, for instance, he started with an IMDB dataset. The team had to combine concepts from possible conversations about the movie data in ways that would fit into the knowledge graph template and generate unique responses from the chatbot. “Thinking about how to turn metadata and numbers into something that sounds human is a lot of fun,” Hutsell says.

“I helped develop features for the bot while I was taking a course in natural language processing," says Danii Huryn, a senior majoring in computer science and physics. "I could see how some of the things I was learning about were coming together into one package to actually work.”

“I helped develop features for the bot while I was taking a course in natural language processing," says Danii Huryn, a senior majoring in computer science and physics. "I could see how some of the things I was learning about were coming together into one package to actually work.”

Language was also a key draw for senior Danii Huryn. He was born in Belarus, moved to California with his family when he was four, and then returned to Belarus when he was 10, staying until he completed high school. He speaks English, Belarusian and Russian fluently and is studying German.

“In Belarus, I helped translate at my church,” he says. “That got me thinking about how different languages work differently and that some are better at saying different things."

Huryn excelled in computer programming and astronomy in his studies in Belarus. His interests also include reading science fiction and playing video games. He began his Emory career on the Oxford campus, and eventually decided to major in computer science and minor in physics.

For the Emora project, he developed conversations about technology, including an AI component, and another on how people were adapting to life during the pandemic.

“The experience was great,” Huryn says. “I helped develop features for the bot while I was taking a course in natural language processing. I could see how some of the things I was learning about were coming together into one package to actually work."

“Psychology plays a big role in natural language processing,” says Sophy Huang, a senior majoring in applied math and psychology. “It’s really about investigating how people think, talk and interact and how those processes can be integrated into a computer.”

“Psychology plays a big role in natural language processing,” says Sophy Huang, a senior majoring in applied math and psychology. “It’s really about investigating how people think, talk and interact and how those processes can be integrated into a computer.”

Team member Sophy Huang, also a senior, grew up in Shanghai and came to Emory planning to go down a pre-med track. She soon realized, however, that she did not have a strong enough interest in biology and decided on a dual major of applied mathematics and statistics and psychology. Working on the Emora project also taps into her passions for computer programming and developing applications that help people.

“Psychology plays a big role in natural language processing,” Huang says. “It’s really about investigating how people think, talk and interact and how those processes can be integrated into a computer.”

Food was one of the topics Huang developed for Emora to discuss. “The strategy was first to connect with users by showing understanding,” she says.

For instance, if someone says pizza is their favorite food, Emora would acknowledge their interest and ask what it is about pizza that they like so much.

“By continuously acknowledging and connecting with the user, asking for their opinions and perspectives and sharing her own, Emora shows that she understands and cares,” Huang explains. “That encourages them to become more engaged and involved in the conversation.”

The Emora team members are still at work putting the finishing touches on their chatbot.

“We created most of the system that has the capability to do logical thinking, essentially the brain for Emora,” Choi says. “The brain just doesn’t know that much about the world right now and needs more information to make deeper inferences. You can think of it like a toddler. Now we’re going to focus on teaching the brain so it will be on the level of an adult.”

The team is confident that their system works and that they can complete full development and integration to launch beta testing sometime next spring.

Choi is most excited about the potential to use Emora to support first-year college students, answering questions about their day-to-day needs and directing them to the proper human staff or professor as appropriate. For larger issues, such as common conflicts that arise in group projects, Emora could also serve as a starting point by sharing how other students have overcome similar issues.

Choi also has a longer-term vision that the technology underlying Emora may one day be capable of assisting people dealing with loneliness, anxiety or depression. “I don’t believe that socialbots can ever replace humans as social companions,” he says. “But I do think there is potential for a socialbot to sympathize with someone who is feeling down, and to encourage them to get help from other people, so that they can get back to the cheerful life that they deserve."

Story by Carol Clark.

To learn more, please visit:

Emory's Natural Language Processing Research Lab, Emory's Department of Computer Science, Emory University

Media contact: Carol Clark, 404-727-0501, carol.clark@emory.edu