A Lifelong Interest Builds a Lasting Legacy

Randall Burkett’s passion for African American history and culture has created a top research collection

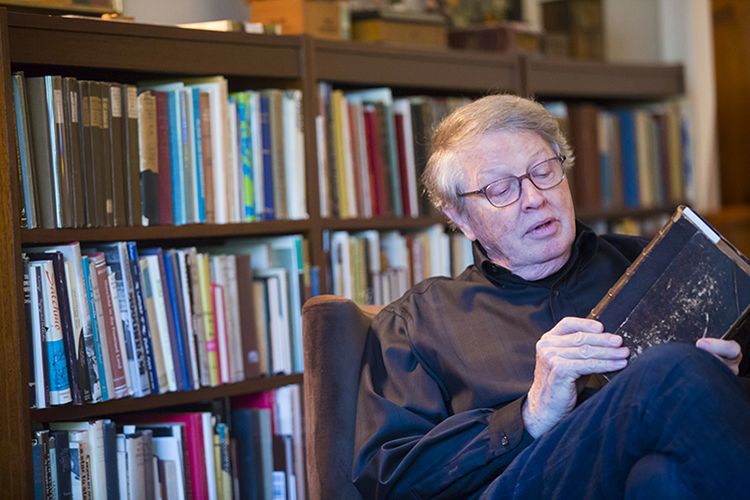

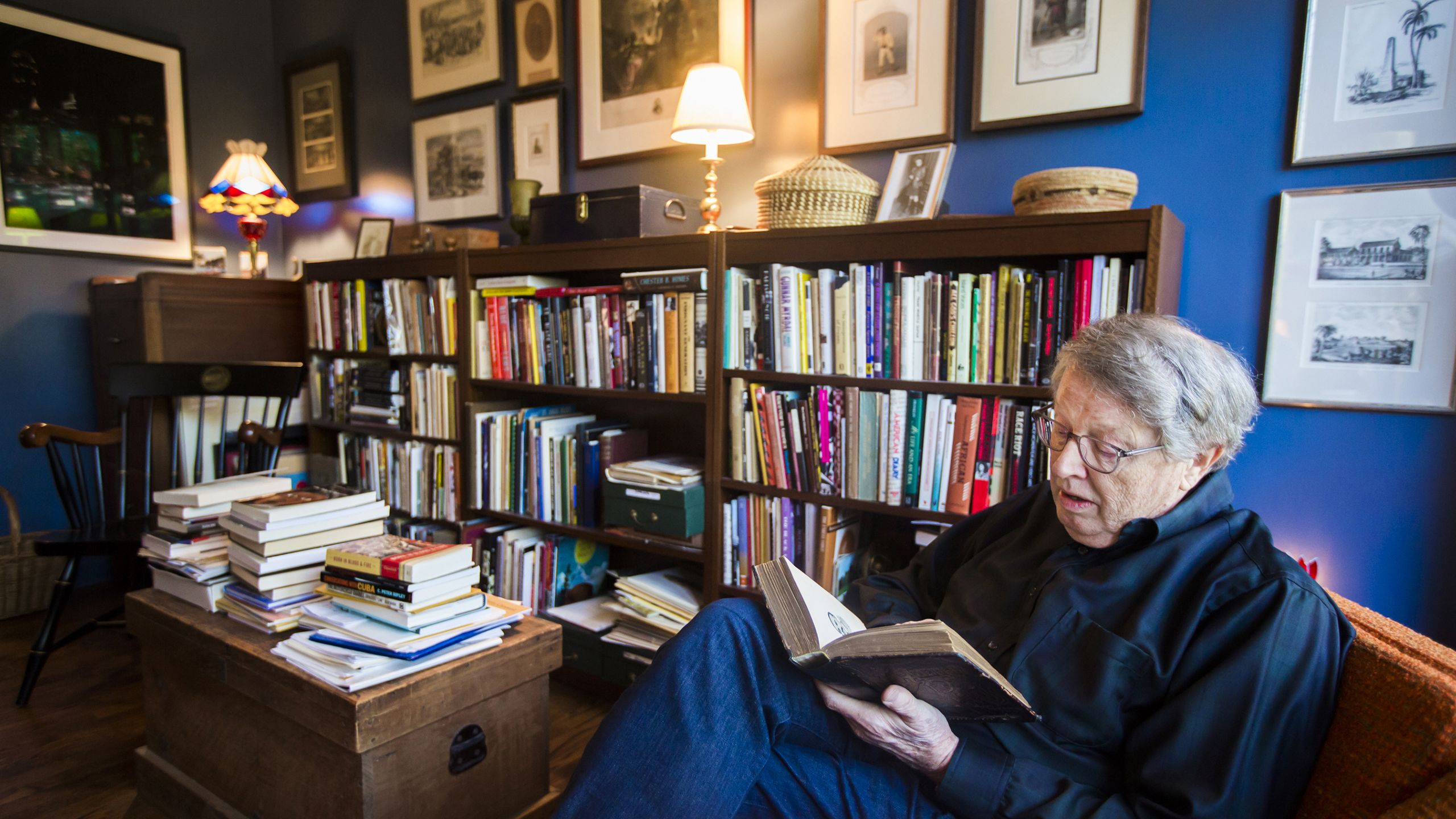

Surrounded by thousands of books on African American history and culture, Randall K. Burkett selects one and settles into a comfortable chair in the library of his home.

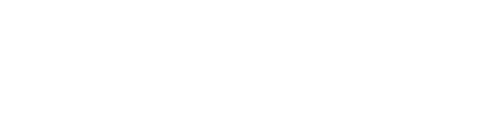

The book, with a well-worn and fraying cover, is “The History of the Negro Race in America” from 1883 by historian George Washington Williams. Burkett remembers his excitement when he stumbled across the volume in 1980 in a store near Boston that mostly sold used furniture.

“It’s inscribed by the author with ‘My study copy,’ ” Burkett says, showing the inscription. “It’s got eight or ten inked marks where he makes little corrections in case he’s able to do a second edition. It’s a great treasure. I’m thrilled to have it.”

Burkett can tell you the background and the collecting story behind nearly all his books. And he can do the same for all of the collections he brought in during his 21 years as curator of African American collections at Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library.

Before he retired in September 2018, his notable “gets” included the papers of historian Carter G. Woodson, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and writer Alice Walker, and the collections of arts historians Camille Billops and James Hatch.

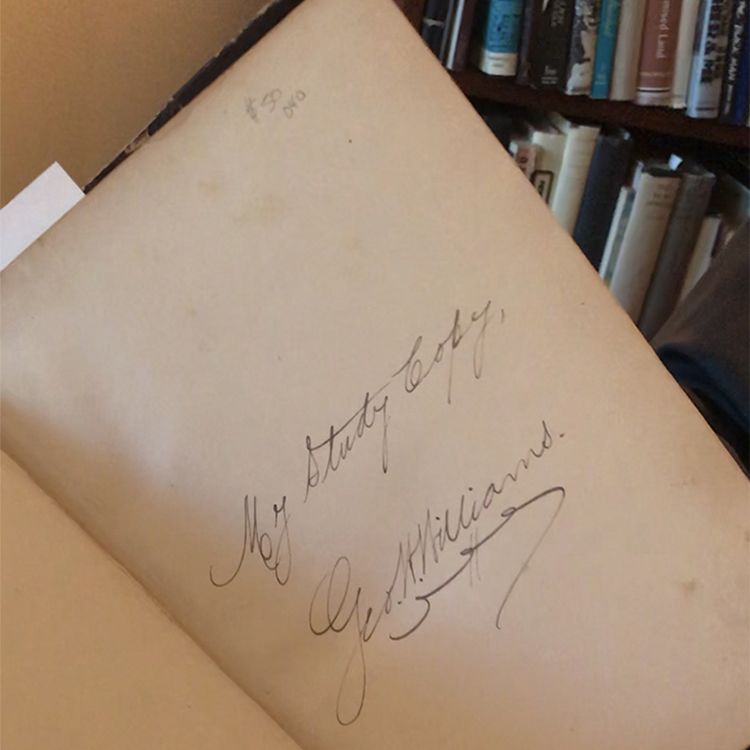

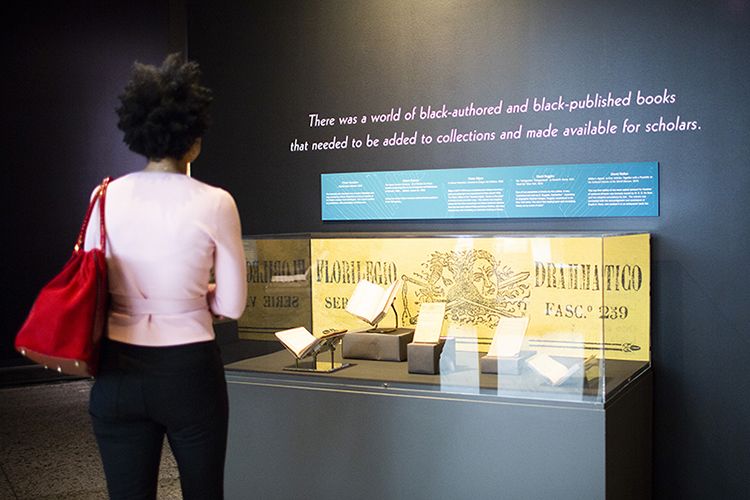

That storied career is celebrated in “Building Emory’s African American Collections: Highlights from the Curatorial Career of Randall K. Burkett,” an exhibition on view in the Woodruff Library’s Schatten Gallery. Included are such treasures as a signed Phillis Wheatley manuscript of her poem “Hymn to Humanity” from 1773 and “Walker’s Appeal,” one of three known existing first editions printed in 1829, formerly owned by W.E.B. Du Bois.

“Randall Burkett is the consummate curator—not only in his own collecting, but also in amassing Emory’s capstone collection of Black Print Culture, a field he helped pioneer,” Kevin Young, director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and former curator of literary collections at the Rose Library, said in September. “The impact of his time at Emory is matched only by his expertise and good humor, all of which have helped make the archives more diverse and inviting.”

An affable personality. An ability to talk, and to really listen, to people. A deep knowledge of African American materials. A keen eye for rare gems. These are a few of Burkett’s traits that have helped him create one of the most extensive archives of African American history and culture among major research universities.

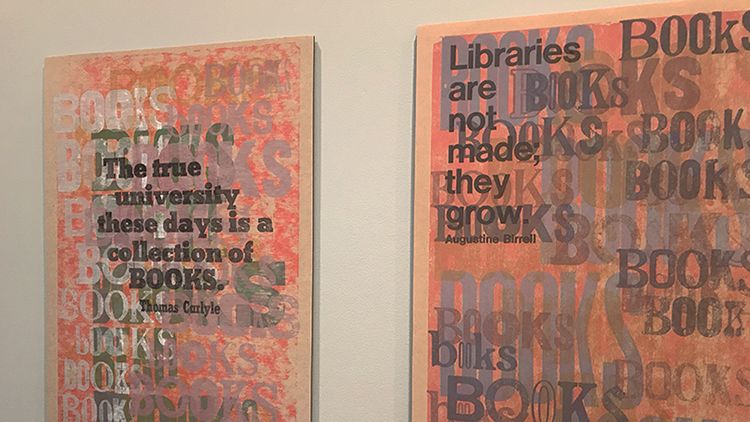

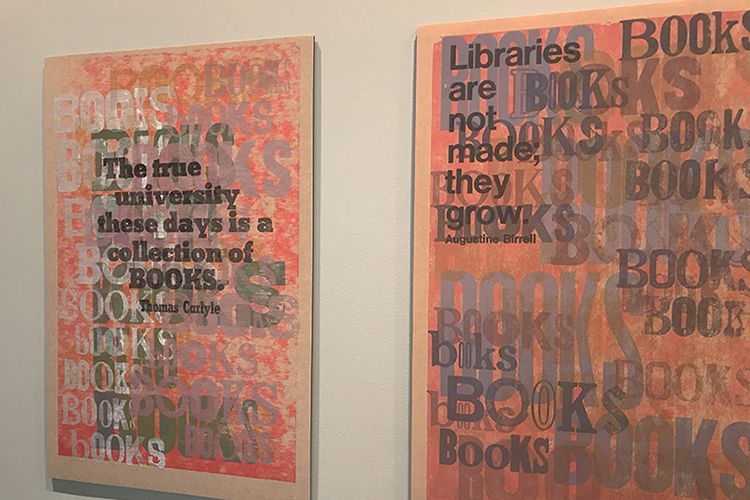

Rose Library’s collections include the papers of artist and letterpress printer Amos P. Kennedy Jr.

One of Burkett’s treasured books is “The History of the Negro Race in America” from 1883.

One of Burkett’s treasured books is “The History of the Negro Race in America” from 1883.

Rose Library’s collections include the papers of artist and letterpress printer Amos P. Kennedy Jr.

Rose Library’s collections include the papers of artist and letterpress printer Amos P. Kennedy Jr.

The Gift of Gab

Born and raised in a small town on the Ohio/Indiana border called Union City, Indiana, Burkett showed an early gift for gab.

Growing up, he would take hours to finish his newspaper route.

He’d start on one side of each street, stop at each house and chat for a bit with customers, and then move on to the next. One woman would get frustrated waiting for him. “She’d ask, ‘Why can’t you just cross the street and deliver my paper? I have to wait until you stop at every house until you make it around to mine!’ ” Burkett remembers with a laugh. “My family knew everybody in town.”

Burkett on his first day of kindergarten.

Not surprisingly, he comes from a family of collectors. His father treasured 900 pocketknives and close to 600 writing instruments, from ballpoints to fountain pens. His mother collected tea cups and paperweights. His grandmother’s weakness was matchboxes. She would empty them out, fill them with pennies and give them to Burkett and his brother for their birthdays. However, Burkett himself didn’t collect much but coins—that is, until he went to Harvard.

Burkett on his first day of kindergarten.

Burkett on his first day of kindergarten.

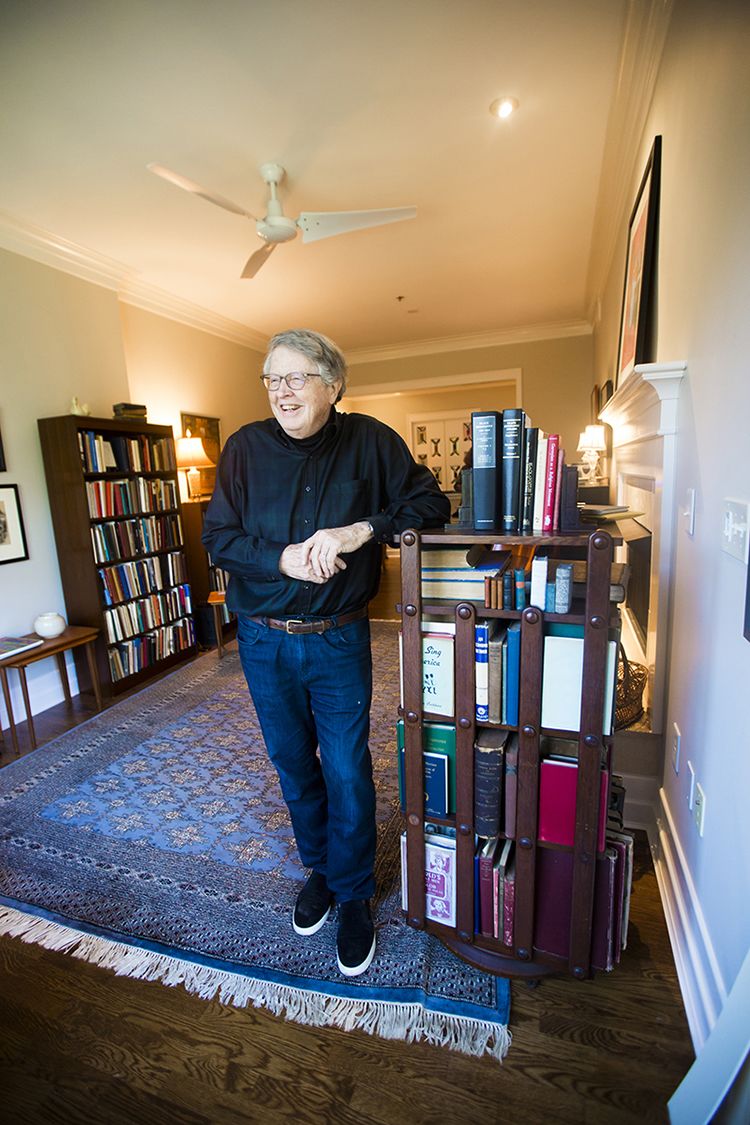

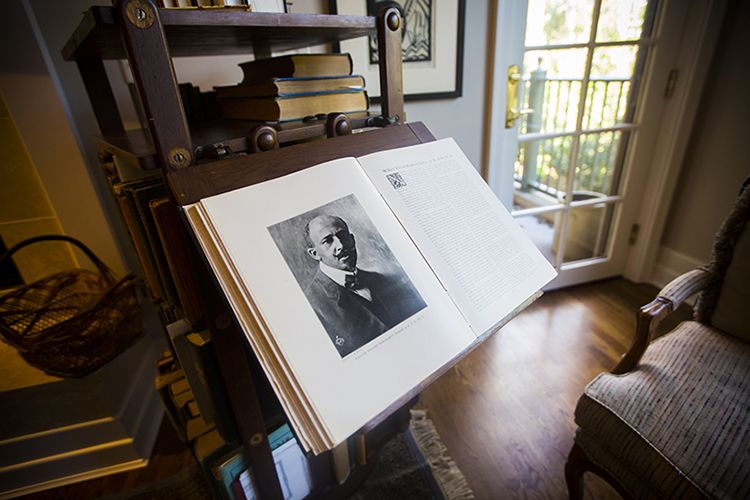

In Burkett’s home library, the rotating wooden bookstand with a foldout writing desktop is more than 100 years old.

In Burkett’s home library, the rotating wooden bookstand with a foldout writing desktop is more than 100 years old.

An Interest Takes Root

Burkett became interested in African American studies in the mid-1960s while pursuing his master’s degree in religious history at Harvard Divinity School.

His research on African American religious history was hampered by scant information on the topic.

After earning his master’s, he began working on his PhD at the University of Southern California, with his dissertation on Marcus Garvey, the Black Power movement, and African American religion.

When he couldn’t find research materials, he resorted to buying his own at bookshops and library sales. His first purchase, still in his home library, was a 1927 first edition of "Who’s Who in Colored America.”

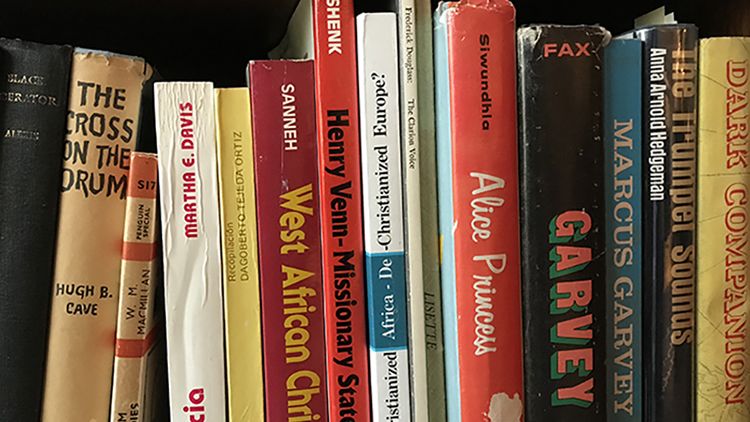

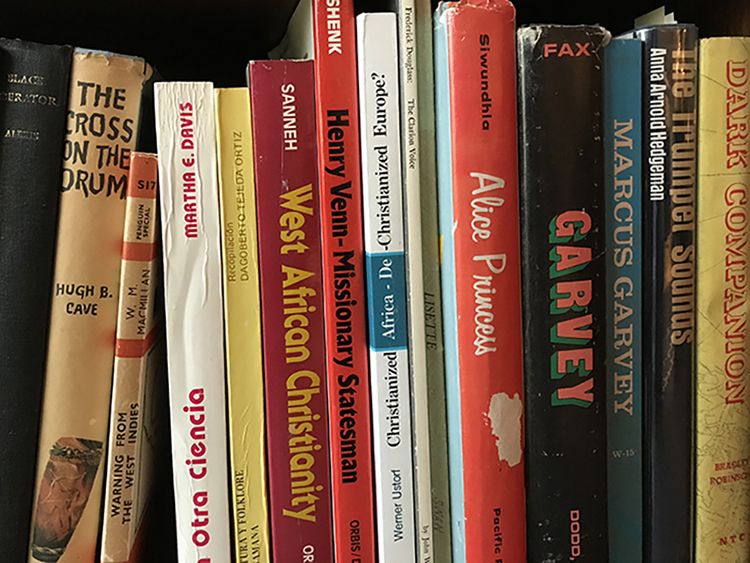

Burkett still has books on Marcus Garvey from his dissertation days.

“There was very little interest in African American religious history in academia at this time,” Burkett says. “Nobody was interested in the books that I was interested in, so they were very affordable.”

Burkett and his wife, Nancy, pictured in Rio de Janeiro in 2003.

Burkett and his wife, Nancy, pictured in Rio de Janeiro in 2003.

After graduation, Burkett and his wife, Nancy (whom he still refers to as my “girlfriend”), settled in Worcester, Massachusetts, where she spent her career as a librarian at the American Antiquarian Society, and he worked at the College of the Holy Cross. The two had met in 1961 as American University undergraduates and married soon after graduation. Burkett continued collecting books on African American history and culture; by then, the deeply rooted interest had become a permanent part of him.

“The National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race” (1919), open to the section on W.E.B. Du Bois.

“The National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race” (1919), open to the section on W.E.B. Du Bois.

Burkett’s career included 12 years as the associate director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research at Harvard (where he worked with Henry Louis Gates Jr.) before he retired from that position. Burkett had nice retirement plans – but then Emory came calling.

Burkett still has books on Marcus Garvey from his dissertation days.

Burkett still has books on Marcus Garvey from his dissertation days.

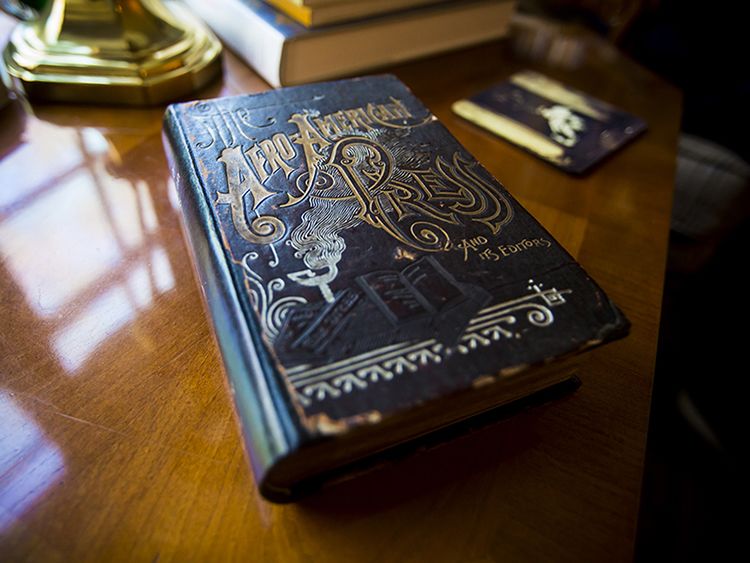

“The Afro-American Press and its Editors” (1891) detailed black periodicals and journalists between 1827-1891.

“The Afro-American Press and its Editors” (1891) detailed black periodicals and journalists between 1827-1891.

The Emory Years

Emory’s African American Studies faculty members, particularly the late professor Rudolph Byrd, were key in encouraging the library to start collections in their field of study – and in Burkett’s hiring in 1997.

Newly retired from the Du Bois Institute, Burkett learned about the job from one of Nancy’s colleagues, who showed him the listing.

“I was certain that Emory wouldn’t be interested in me, but I suspected they didn’t have a clear idea what they ought to collect. So I thought I would come down and offer suggestions as to how they might focus,” Burkett said in a 2016 interview. To his surprise, but apparently no one else’s, he was offered the job. “I was astonished and delighted, I must say. It’s the best move that I’ve made. It’s been a tremendous opportunity and a great pleasure.”

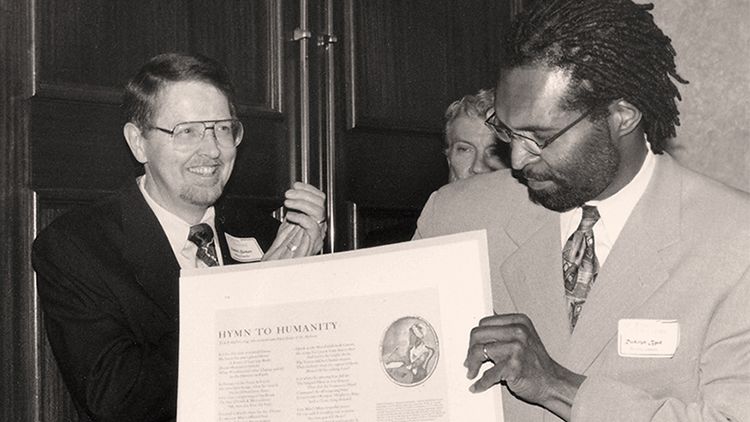

Rudolph Byrd (right), professor of African American Studies, with Burkett in 1997.

Once Burkett had been hired, Byrd brought him to a lawn party before the fall semester started. When Burkett introduced himself to one guest as the new curator of African American collections, the woman pulled back her hand and scoffed, “That’s just like Emory to hire a white guy to be in charge of African American collections!”

But anyone who knows Burkett, or has talked with him for even a few minutes, can sense his passion for ensuring that African American history and culture – conveyed through the African American voice – is well represented in Emory’s collections. And his enthusiasm is contagious.

“He’s so easy to talk to,” says Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, associate professor of American Studies and African American Studies. “Any book that came out, he knew about it. He was always talking about one of the collections. He created this buzz and energy around the collections that got people excited about the materials.”

Burkett with the late Dorothy Cotton (left), former education director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and former Rose Library director Rosemary M. Magee in 2013.

Jennifer Gunter King, who became the Rose Library’s director in October 2018, says its African American collections were part of what inspired her to pursue the job.

After meeting Burkett and learning more about how he built the archive over the years, she understood his foresight and vision in collecting materials that tell a vivid history of the many people and organizations that compose America’s history – a story of struggle and success, of community and faith, and humanity.

“Randall has played a vital role in building an extraordinary collection at the Rose Library,” King says. “Throughout his curatorial career, his efforts have created not only an extensive archive documenting African American history and culture, but also an amazing network of people connected to these collections.

“This network includes donors, families and descendants, community members, scholars, artists, students, and the general public. All these people significantly enrich our knowledge and appreciation of the history represented in these singular collections, as well as assure us that the past is not forgotten.”

Rudolph Byrd (right), professor of African American Studies, with Burkett in 1997.

Rudolph Byrd (right), professor of African American Studies, with Burkett in 1997.

Burkett with the late Dorothy Cotton (left), former education director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and former Rose Library director Rosemary M. Magee in 2013.

Burkett with the late Dorothy Cotton (left), former education director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and former Rose Library director Rosemary M. Magee in 2013.

Jennifer Gunter King, new director of the Rose Library.

Jennifer Gunter King, new director of the Rose Library.

The Burkett Legacy

Emory’s African American collections reflect the legacy of more than Burkett’s knowledge and persistence.

They are testimony to the relationships he’s built with donors, book dealers, and collectors over the years.

One notable example: the Billops-Hatch archives. This trove, collected over four decades by Camille Billops and James Hatch, contains African American-authored books and play scripts, theater and movie posters, periodicals, photographs, and recordings of their own salon-type interviews with African American artists, writers, and performers.

“They live in New York,” Burkett says. “They could have placed these collections anywhere. There were a number of institutions interested.”

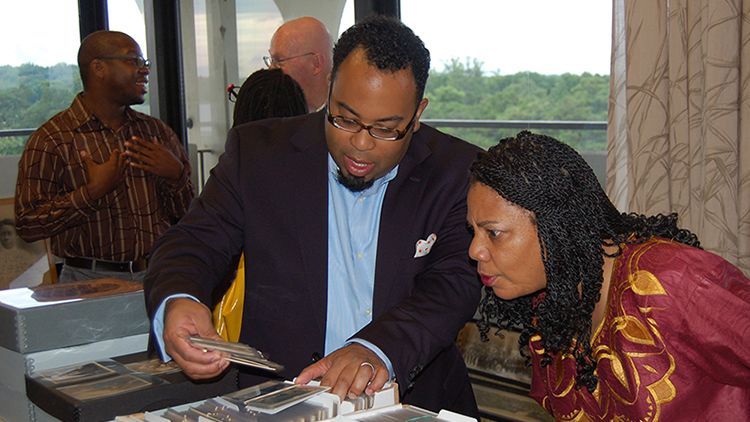

Billops and Hatch review materials from their collection with Burkett in 2012.

Burkett asked Billops what she hoped to see for the collection. Extensive cataloging of the materials? A fellowship for researchers to study in the collection? An exhibition? A special room dedicated to their collections?

“Yes, we want all of that,” Burkett says she responded. The business of collecting, he says, is also about listening to what the donor wants – and making sure you can deliver before you make a promise. (And yes, all four of those wishes for the Billops-Hatch collection came true.)

Camille Billops has been so pleased with the treatment of the archive, she’s become an amazing advocate for Emory, directing other donors to place their papers with the Rose Library and helping to bring in additional collections, Burkett says.

Camille Billops and James Hatch view the 2016 “Still Raising Hell” exhibition, based on their collection.

Another standout collection is the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection, which became the Rose Library’s first major photo archive when it was acquired in 2012. It’s a story of serendipity, for Burkett and for Emory.

Burkett visited rare book seller Robert Langmuir in Philadelphia many times over the years, purchasing books and other items from him, and the two became friends. Langmuir collected African American materials, his fondness inspired by his childhood years growing up in African American neighborhoods in Philadelphia.

During one visit, Langmuir told Burkett he was going to refocus his collecting and wanted to get rid of everything, including a large collection of photographs, albums, and scrapbooks he had amassed from his visits to flea markets, auctions, estate sales, and other means. “How much for all of it?” Burkett asked, intrigued.

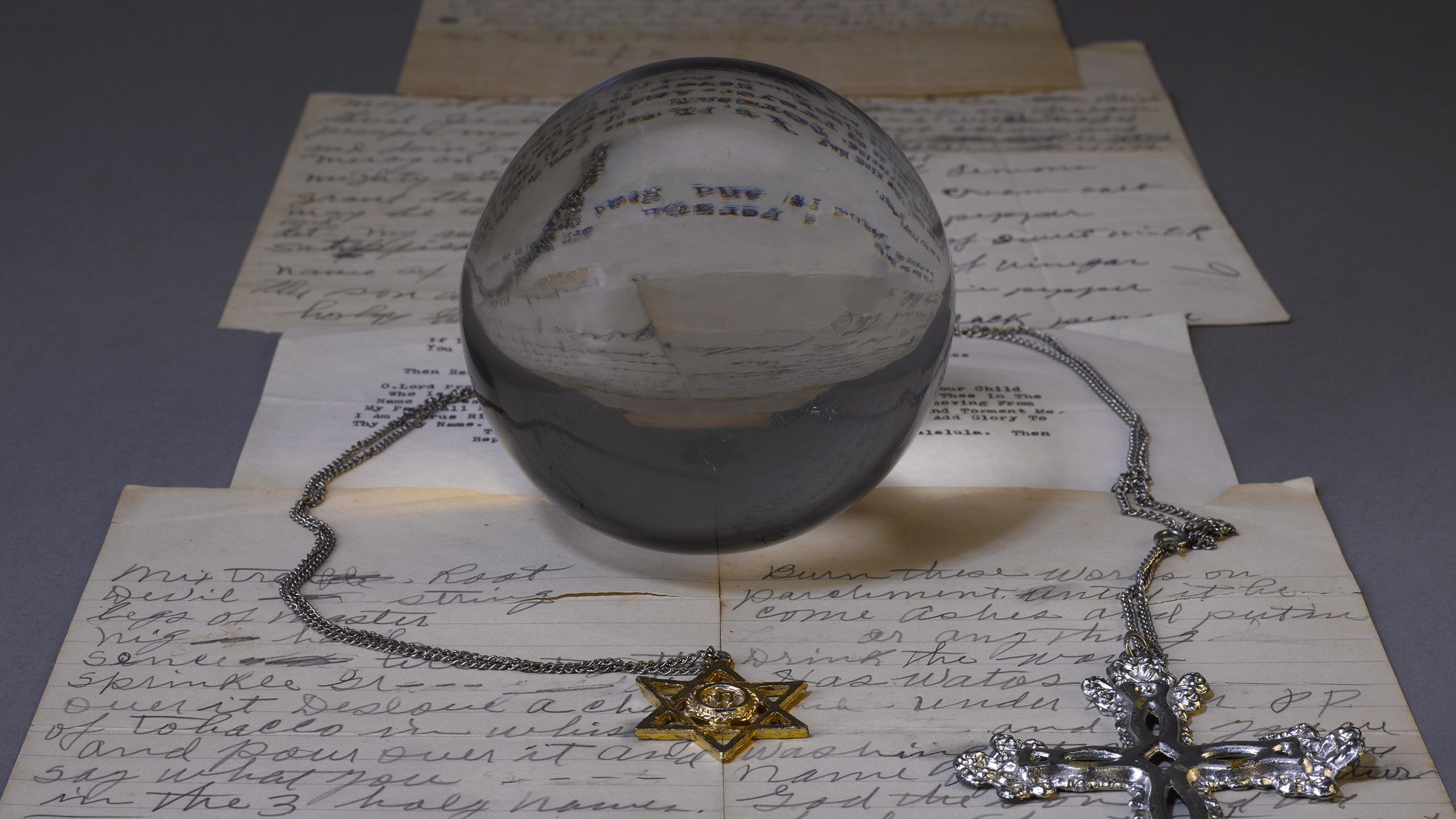

An image from the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection.

The Rose Library’s Langmuir collection contains more than 12,000 images that depict African American life and culture from the late 1880s to the 1970s. It includes an astounding array of photographs, tintypes, daguerreotypes, cabinet cards, panoramas, and photographic postcards. Many of the photographs were taken by African American photographers, and over 10,000 images have been digitized. The collection has sparked class research, exhibits, and even faculty-authored books.

Browse a digitized portion of the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection

Wallace-Sanders has a second book on mammies in progress, and she is curating an exhibit on the subject that opens in the Schatten Gallery this spring. Both projects draw heavily from the Langmuir collection. She remembers the day Emory hosted a media event to announce it had acquired the Langmuir photograph collection. Boxes of photos were spread across library table tops. Students, faculty, staff, reporters, and photographers examined the images with alternating fascination and excitement.

Kevin Young and Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, associate professor of African American Studies, examine the Langmuir photo collection in 2012.

“I was there the day the collection came in,” Wallace-Sanders recalls. “I was dancing around. I was trying not to scream with excitement. That was an extraordinary day.” Prior to that day, she says, she was at a point where she was looking beyond Emory, wanting to further her research.

“It was a game changer for me,” she says. “I’m so glad that I didn't give up on Emory. The day the Langmuir photographs arrived, I knew I could work in that collection for the rest of my career.”

Burkett’s legacy is secure in other ways. A few years ago, the Burketts established the Randall and Nancy Burkett Award for Research in Black Print Culture. The award supports researchers exploring the Rose Library’s holdings of rare manuscript, ephemeral, photographic, and print materials produced by and for African Americans. Its purpose? To encourage research and writing on the history and importance of black printing, authorship, and publishing.

The Burketts donated a large portion of their personal collection to Emory in 2011.

Burkett also donated a substantial portion of his personal collection of African American books, photographs, artifacts, and other materials to the Rose collection. The materials include the papers of William H. Scott (1848-1910), a 12-year-old slave who escaped and became an aide to a Union Army officer, who educated him.

Scott went on to become a teacher, minister, political activist, and one of the 29 founding members of the Niagara Movement, which was the predecessor of the NAACP. Scott’s grandson bequeathed the papers to Burkett in the hope his grandfather’s story would be made public. The Scott archive includes a Civil War sword, which Scott took from the body of a Confederate soldier during a lull in the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Burkett displays a Civil War sword from the William H. Scott collection.

“I would love to see someone write a book about William H. Scott and use these papers to research it,” Burkett says. “He has an amazing life story.”

Billops and Hatch review materials from their collection with Burkett in 2012.

Billops and Hatch review materials from their collection with Burkett in 2012.

Camille Billops and James Hatch view the 2016 “Still Raising Hell” exhibition, based on their collection.

Camille Billops and James Hatch view the 2016 “Still Raising Hell” exhibition, based on their collection.

An image from the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection.

An image from the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection.

Kevin Young and Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, associate professor of African American Studies, examine the Langmuir photo collection in 2012.

Kevin Young and Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, associate professor of African American Studies, examine the Langmuir photo collection in 2012.

The Burketts donated a large portion of their personal collection to Emory in 2011.

The Burketts donated a large portion of their personal collection to Emory in 2011.

Burkett displays a Civil War sword from the William H. Scott collection.

Burkett displays a Civil War sword from the William H. Scott collection.

What the Future Holds

The future of Emory’s African American collections is in good hands with Pellom McDaniels III as the curator.

Thinking he would retire in the near future and wanting to prepare a successor, Burkett first approached McDaniels in 2007 about the job.

The two had met in 2001 when McDaniels was a graduate student at Emory. A professor asked McDaniels to help prepare an exhibit using materials from the collections. This gave McDaniels a chance to work in the archives, where Burkett regaled him with stories about poet Langston Hughes and his leftist friends. From the start, McDaniels admired Burkett and his deep knowledge of the collections. “I thought he was a fountain of knowledge,” McDaniels recalls.

But in 2007, McDaniels had just started his first teaching job at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. The two agreed to wait a few years. In 2010, McDaniels became associate curator of African American collections, traveling between Atlanta and Kansas City. In 2012, the time was right. McDaniels settled in Atlanta to become the curator of the collections, and Burkett became research curator. McDaniels says he has learned much from Burkett, perhaps most importantly to listen to donors.

“While the materials we collect are important, cool, and unique, what’s most significant are the relationships we have with our donors. It’s important that we respect their stories, so we will have a greater appreciation and reverence for the materials and the experiences connected to them,” McDaniels says.

Pellom McDaniels is now the curator of African American collections.

As for Burkett, he’s still at work on a few projects. He’s compiling a complete list of city directories within the Rose Library’s African American collections. Most of them chronicle black businesses and professionals in various cities from the early to mid-1900s. The oldest one in the collection is from 1891 and covers nine Eastern U.S. cities. “We will send this list to book dealers and ask if they can locate any that are not on the list,” he says.

He also plans to work on collective biographies of African Americans in specific areas, such as a who’s who among Baptist ministers.

Under McDaniels, the Rose Library’s African American collection are expanding more into the community. Exhibits are going out into schools, where materials are being incorporated into classwork. He is also partnering with cultural organizations such as the Alliance Theatre, which mounted an exhibit from Pearl Cleage’s papers when one of her plays was being produced there a few years ago.

“I can’t imagine anyone else I would rather hand this over to,” Burkett says. “With Pellom, we’re going to continue to build this archive. He has a commitment to broadening the use of the collections, and that will be an important next step.”

Two students work with the African American collections in the Rose Library.

University Librarian Yolanda Cooper is equally optimistic about expanding on and honoring Burkett’s vision.

“Emory University has one of the best collections of African American materials in the country due to the exceptional work of Randall Burkett, the architect of this amazing resource,” she says. “We have been very fortunate to benefit from someone who saw the intrinsic value of collecting this precious history and telling stories that are quite often missing from other collections.”

“We are also very fortunate to have Pellom McDaniels, the current curator for African American collections at Emory, to continue his work in its development,” she adds. “This archive remains one of our collecting priorities, and we look forward to its advancement in the future.”

Pellom McDaniels is now the curator of African American collections.

Pellom McDaniels is now the curator of African American collections.

This quote from Burkett appears in the exhibition that highlights his curatorial career.

This quote from Burkett appears in the exhibition that highlights his curatorial career.

Two students work with the African American collections in the Rose Library.

Two students work with the African American collections in the Rose Library.

University Librarian Yolanda Cooper.

University Librarian Yolanda Cooper.

Story by Maureen McGavin

Design by Gretchen Warner