STEPPING UP

Wherever they live, whatever their profession, Emory alumni share a common pursuit: service to their communities

Overcoming a history marked by struggle and hardship, a doctor builds a medical career, then uses her success to care for society’s most vulnerable in her adopted country.

A young man witnesses homelessness in an island nation devastated by natural disaster, then comes back to Atlanta resolved to improve the lives of homeless people in his hometown.

Remembering his humble beginnings, an attorney graduates from one of the nation’s most prestigious law schools and makes the life-altering decision to devote himself to helping disadvantaged children pursue dreams of education and professional success.

These Emory alumni and many more have built upon a foundation they say was strengthened on Emory’s campus—to not only do well but to do good in the world.

Emory attracts socially engaged students, encouraging them to lead in building programs to address the issues they care about most. More than five in six students participate in community service and volunteer work, according to the 2017 Emory College Senior Survey, and students have founded 118 special interest organizations to support the community within and outside the university.

Examples: the Homeless Outreach and Awareness Project, which seeks to reduce the distance between the homeless and the rest of society through service, education, and advocacy; and Next Generation Men and Women, which partners Emory undergraduate students with local high schoolers to encourage them to graduate and pursue an occupation or higher education.

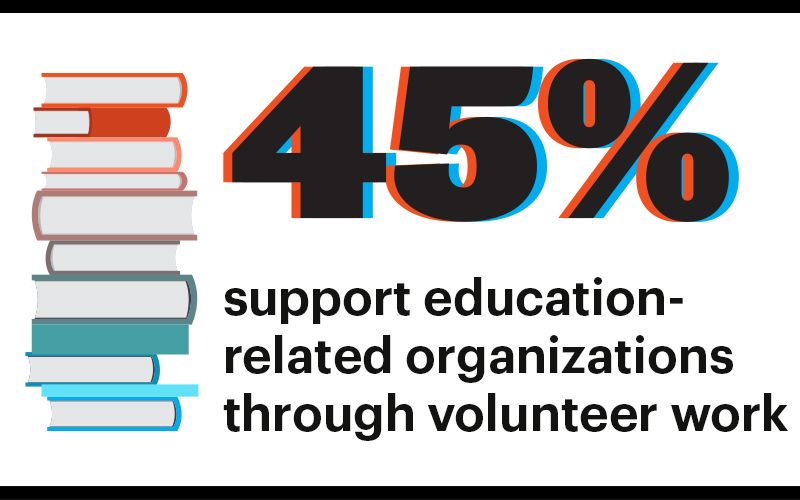

And when they leave, Emory graduates do extraordinary things. According to a recent survey, nearly 60 percent of alumni regularly volunteer in their communities—more than double the national average of 25 percent, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Service feels like part of the fabric of the Emory experience. Our alumni and students devote great energy and passion to the causes they believe in—whether through our annual Emory Cares International Service Day projects or those they champion in their communities every day. We attract students who consider service a part of their academic calling, encourage and cultivate that spirit while they are on campus, and support those efforts when they leave,” says Sarah Cook 95C, senior associate vice president for alumni engagement. “Community service enriched my own experience at Emory, and I am incredibly proud that our alumni and students continue to be drawn to serve and lead positive change in their communities and around the world.”

Taos Wynn founded the Perfect Love Foundation in Atlanta “to harness the collective power of love to address society’s problems.” Photo by Kay Hinton.

Taos Wynn founded the Perfect Love Foundation in Atlanta “to harness the collective power of love to address society’s problems.” Photo by Kay Hinton.

Taos Wynn 06Ox 09C is a provocateur.

His goal: to incite love, hope, and action.

Taos Wynn founded the Perfect Love Foundation in Atlanta “to harness the collective power of love to address society’s problems.” Photo by Kay Hinton.

The youngest of two sons from a military family, Wynn watched his parents—Raymond, a US Army veteran, and Elaine, an educator—open their home to endless streams of kids and neighbors, always willing to help in any way they could.

It came naturally to Wynn to do the same, but it was a trip to Haiti to assist after Hurricane Sandy that propelled him to do more than just acknowledge the greater problems he saw both in developing countries and on the streets of Atlanta.

Beginning with a small contingent of friends who joined him to bring sandwiches to homeless people around Atlanta, Wynn grew that small outreach into the Perfect Love Foundation, the manifestation of his desire to harness the collective power of love to address society’s problems.

“I hold true to the belief that all human progress requires collective action and cannot be limited to one ethnic group, race, or gender,” Wynn says. “It requires activities that foster healthy relationships and an understanding of other people’s cultures and perspectives, so we can better relate to each other and have meaningful conversations that lead to change.”

Three fundamental beliefs underpin all of Wynn’s advocacy efforts—“everyone matters, everyone deserves respect, and everyone has the ability to make a difference”—and his foundation is built on the philosophy that all of these can be accomplished through the fundamental understanding that we are all more alike than we are different.

Since late 2013, the foundation has grown to champion causes including empowering students and citizens as change leaders, promoting unity and understanding among all people, meeting the needs of at-risk groups, and providing relief for communities impacted by disaster. Wynn was named a 2017 Millennial of the Year and received the Georgia Outstanding Citizen Award, one of the state’s highest civilian honors.

“It is our responsibility to instill and share a greater sense of valuing all people,” Wynn says. “For a lot of the challenging or complex issues of the world, we are going to need as much help as we can get. We do not want to dismiss or devalue anyone because everyone has the ability to make a difference and ultimately further social progress.”

Many of the foundation’s volunteers are millennials, and several of their programs focus on preparing children and teenagers to be change leaders for the future. Wynn says teaching respect, understanding, and love for others are concepts he grew up with and Emory reinforced.

“When there is something going on in society at large that we do not agree with, we must accept accountability for those things,” he says. “This isn’t always easy, but it is up to all of us to accept the responsibility of seeing changes through.”

Hassanatu Blake (right), cofounder of Focal Point Global, greets a community entrepreneur.

Hassanatu Blake (right), cofounder of Focal Point Global, greets a community entrepreneur.

In a way, Hassanatu Blake 05MPH was born for service.

A native of Limbe, Cameroon, she was born to a Cameroonian mother and an American father who was serving in the country as an economist with the Peace Corps. The couple had three of their five children in Cameroon before moving to Baltimore, Maryland, with their young family.

Hassanatu Blake (right), cofounder of Focal Point Global, greets a community entrepreneur.

“My father and mother were keen on making sure we knew not only what went on in the United States, but around the world, particularly back home in Cameroon,” Blake says.

Throughout their education, Blake and her twin sister, Hussainatu, were active in volunteer activities and afterward pursued professions that addressed critical issues including access to education, HIV/AIDS prevention, and aiding victims of human tracking. Through these experiences, one common question emerged: “How do we get youth to tackle issues in their own communities?”

The Blakes established Focal Point Global, a nonprofit “focused on connecting youths to have discussions about global issues, then linking them to local organizations to complete projects to address those issues.”

Focal Point Global works to facilitate global connections through technology—including modern social media tools—to link young people with experts and peers around the world who are addressing the issues they face without leaving their city, state, or country.

Since 2010, Focal Point Global has gone on to address high HIV rates in developing countries and a resurgence of HIV incidence in the US. It also has expanded to tackle issues including child trafficking and youth employment and entrepreneurship in disadvantaged areas.

Gulshan Harjee (left), cofounder of the Clarkston Community Health Center.

Gulshan Harjee (left), cofounder of the Clarkston Community Health Center.

Gulshan Harjee 82M 85MR knows what it is like to have to flee your home for a foreign country, hoping to find stability there.

Gulshan Harjee (left), cofounder of the Clarkston Community Health Center.

Three times she had to leave a country where she lived when war or unrest threatened her safety. First her native Tanzania, then Pakistan, then Iran where she attended university.

When the US issued sanctions against the country after the American embassy was seized in 1979, Harjee came to Atlanta where her fiancé was studying law.

“After coming to the United States, I was able to interview at Morehouse, but it was only a two-year medical school and I had to transfer to another medical school to graduate,” Harjee says, adding that her acceptance was facilitated by Louis Sullivan, founding dean and first president of the Morehouse School of Medicine. “He listened to my story and, by giving me that thirty minutes of his busy day, he totally changed my life.”

After finishing the program at Morehouse, and with a recommendation from Sullivan, she was accepted to Emory School of Medicine.

After completing her training, she remained in Decatur, practicing internal medicine and doing community work. In 2015, her years of community involvement led her to help found the Clarkston Community Health Center—a comprehensive, free clinic that provides medical, dental, and mental health care to indigent, uninsured, and underinsured patients—with her colleagues, Atlanta pharmacist and Emory parent Saeed Raees and Emory cardiologist Arshed Quyyumi, a professor of medicine and director of Emory’s Clinical Cardiovascular Research Institute.

The center serves impoverished patients without health insurance, about 80 percent of them refugees and immigrants.

“If you sat down and talked to the families of patients who come to the Clarkston Community Health Center, you would wonder how these people make it, how do they pay bills and buy food?” says Harjee.

Care is provided by physicians and other medical practitioners from Atlanta and the surrounding areas who donate their time and services to the clinic. Through the years, Harjee’s life has been marred by tragedy and challenges, but her dedication to her community has never wavered.

“I came here with nothing, and when I think about where I grew up and what I went through compared to what I am able to do today, I feel I need to give back,” she says.

James O'Neal, founder of the educational nonprofit Legal Outreach.

James O'Neal, founder of the educational nonprofit Legal Outreach.

For a while, as a student at Harvard Law School, James O’Neal 77Ox 79C felt adrift, disconnected from the rudder he had felt steering him all of his life.

James O'Neal, founder of the educational nonprofit Legal Outreach.

“Growing up in the sixties and seventies, I saw the law as a tool of change and I wanted to pursue a career where I would be informing, helping, and advocating for people,” he says.

But when he saw his classmates taking high-paying private-sector jobs, he began to question his focus.

The moment of decision came during his third year of law school, when he applied for and was awarded the Public Interest Law Fellowship, funded by members of the class of 1982 to support one classmate to do something new and different in the field of public interest law.

O’Neal partnered with a youth guidance center in Harlem to experiment with his idea of combining law and education to affect the career aspirations of urban youth positively.

During the year, he taught elementary and high school students, as well as those in a program for first-time offenders. In each setting, he had experiences that showed he could make a difference.

“They equated the legal system with an oppressive system based on the encounters they’d had with police,” he says. O’Neal fashioned his classroom into a courtroom, allowing students to serve as lawyers and judges. It led to a slow change in their perceptions.

Realizing he was exactly where he needed to be, O’Neal incorporated Legal Outreach as an educational nonprofit that celebrated its thirty-fifth anniversary this year. Its partners include seven law schools, forty law firms, judges, and more than two hundred attorneys.

As of 2018, 731 students have completed College Bound, the organization’s comprehensive, four-year program designed to equip students from underserved communities with the academic tools they need to succeed. Of those, 99.3 percent have attended college and more than 75 percent of graduates have matriculated to top-ranked colleges and universities including Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Swarthmore, Cornell, NYU, Williams, Wesleyan, and more.

“We seek to provide kids with hope, first and foremost,” O’Neal says. “We want to provide them with a clear vision of what they can achieve.”

After supporting his three children, two of whom are now surgeons, through school; founding a thriving seven-physician practice; and spending more than twenty-five years doing teaching rounds at Grady Memorial Hospital, Robert K. Shuler Sr. 60M 61MR had more than earned the right to slow down.

Robert Shuler, a medical missionary for Flying Doctors of America, with patients in Kenya.

He decided it was time to “do all the crazy things I’d never been able to do.”

For some retirees, that might mean hitting the beach or spending days fishing or playing golf. For Shuler, it meant travel, but not quite the kind most retirees pursue. Since retiring in 2008, Shuler regularly joins medical mission trips with Flying Doctors of America and the Peachtree Road United Methodist Church. In his travels, he’s worked with patients in Haiti, Peru, India, Kenya, Madagascar, Panama, Zambia, Paraguay, and the Republic of Georgia.

Shuler went on his first medical mission trip as a senior resident in pediatrics and always hoped to be able to perform a similar service again.

“I’ve been to Kenya three times and the Republic of Georgia four times with Peachtree Road,” says Shuler. “My most recent trip was to Zambia.”

The outpouring of gratitude and support from the communities he has served is astounding, he says. “In so many parts of the rest of the world the medical care is so poor, I feel like if my old brain will still keep working, it is the least I can do. It also helps keep my medical skills up; it keeps me on the go and maybe I can make some less fortunate lives a little better,” Shuler says.

An active member of the Emory School of Medicine Alumni Board, Shuler serves on the nominating committee of the Emory GO-TRAVEL (Global Outreach Traveling Resident Award to Visit, Experience, and Learn) program, which supports resident education in unique international training experiences.

“As long as I am physically and mentally able, I plan to continue to help others,” the eighty-three-year-old Shuler says. “I get more out of it than I probably give. The feeling of helping someone else is enough. I’ve been in places where children probably had never seen a doctor. I feel like I am giving back for the good life I have had.”

Robert Shuler, a medical missionary for Flying Doctors of America, with patients in Kenya.

Robert Shuler, a medical missionary for Flying Doctors of America, with patients in Kenya.

In her career as an attorney focused on collaborative reproduction and surrogacy, Rachel Loftspring 04C is accustomed to protecting the rights of parents even before they’ve become parents.

Rachel Loftspring launched Bringing Up Family to help parents advocate for family-friendly change.

And as a mother of two young children—Mila, three, and Levi, one—Loftspring understands firsthand how challenging it is for working parents to integrate the jobs that support their families and the families they are supporting—especially when relatively few employers provide paid parental leave and very few laws exist to protect or provide family or medical leave.

One of the ways Loftspring chose to address these issues was with Bringing Up Family, a website that offers free information, advice, and resources parents can use to advocate for change in their local governments, at home, and in their workplaces.

“Parents are extremely busy and adding activism to their daily to-do list is asking a lot. But there are thirty-five million American families with children under eighteen and the goal is to harness that power by giving individual parents access to resources so that, person by person, we can come together and reshape the system,” Loftspring says.

Through the website BringingUpFamily.org, Loftspring marshalled her professional and personal experience to provide concise guides parents can use to take “that first and really important step toward change.”

“Taking effective action can be big or small,” she says. “Advocating is not easy and a lot of times you aren’t successful, but it is about continuing to take action, continuing to educate, and continuing to push for change.”

Rachel Loftspring launched Bringing Up Family to help parents advocate for family-friendly change.

Rachel Loftspring launched Bringing Up Family to help parents advocate for family-friendly change.

Munir Meghjani cofounded H.O.P.E. to connect nonprofits with young adults who can help them thrive.

Munir Meghjani cofounded H.O.P.E. to connect nonprofits with young adults who can help them thrive.

“Knowledge is everywhere right now,” says Munir Meghjani 08Ox 10C. “The internet revolutionized that. Google put it all right at your fingertips.”

Munir Meghjani cofounded H.O.P.E. to connect nonprofits with young adults who can help them thrive.

However, the test for present and future generations is not simply acquiring knowledge, but developing the ability to deploy research, discoveries, works, and breakthroughs in the service of what is good—to enrich, change, and save lives.

This is what drives Meghjani, a commercial and investment real estate broker and entrepreneur in Atlanta who believes his Emory education allowed—perhaps even required—him to pursue his calling for philanthropy, volunteerism, and altruism.

Meghjani is cofounder and executive director of H.O.P.E. (Helping Organizations & People Everywhere), an Atlanta-based nonprofit that connects organizations and charities worldwide with young adults who have the skills and desire to create sustainable solutions to fundamental societal problems. The issues range from global poverty to rights and empowerment for women and girls in developing countries.

He also played a critical role in the start of Activist Recruiting Organizing & Mentoring in Atlanta—a group created as a “gateway” for mobilizing interested citizens on social justice initiatives through networking, training, and mentorship with social justice groups around Atlanta.

“What we need to understand is that, as a world, there is only a limit to how high any of us can go when others are still down,” Meghjani says.

When people lack access to knowledge, they lack access to power and those with knowledge must share it.

“It’s only when you accept the fact that you’re a global citizen, that you realize your actions have a butterfly effect no matter where you are,” he says. “You may not see it today, but you’ll feel the impact tomorrow.”

Gabriel Wardell contributed to this story.

Causes and Effects

Although nearly 60 percent of Emory alumni serve their communities, fewer than 30 percent have donated to the university. Gifts to Emory support future leaders who will collectively impact all areas of need, from homelessness to climate change. Learn more and register for the 15th anniversary of Emory Cares International Service Day .

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Magazine,

Emory News Center, and Emory University.