It's alive!

From labs to libraries, theaters to theology, Frankenstein at 200 sparks wonder and debate

Initially dismissed by critics as a gothic trifle, Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein: Or, the Modern Prometheus” is now a beloved classic and a cultural icon. The book turns 200 this year, has never been out of print and remains one of the most read novels on U.S. college campuses.

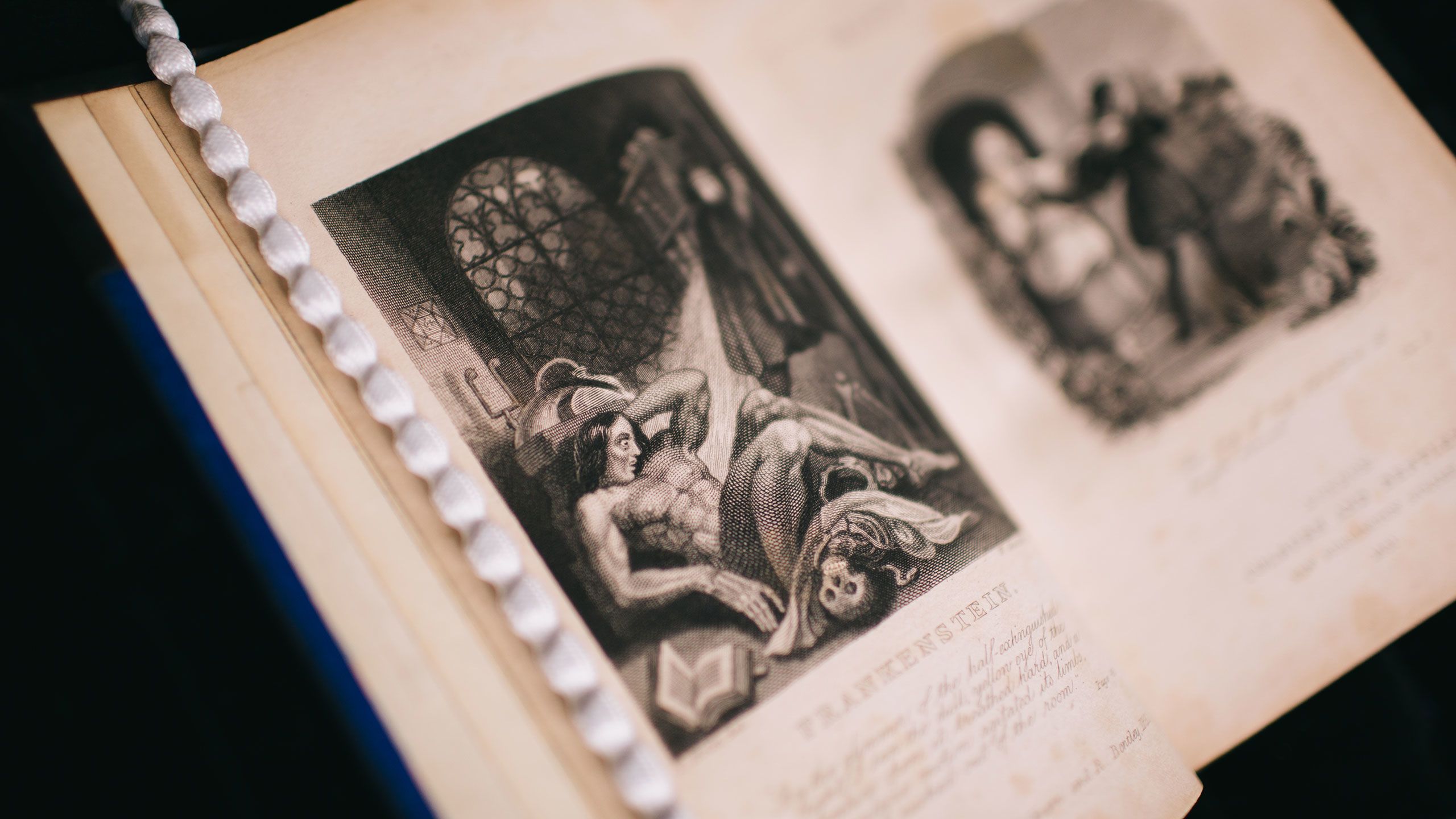

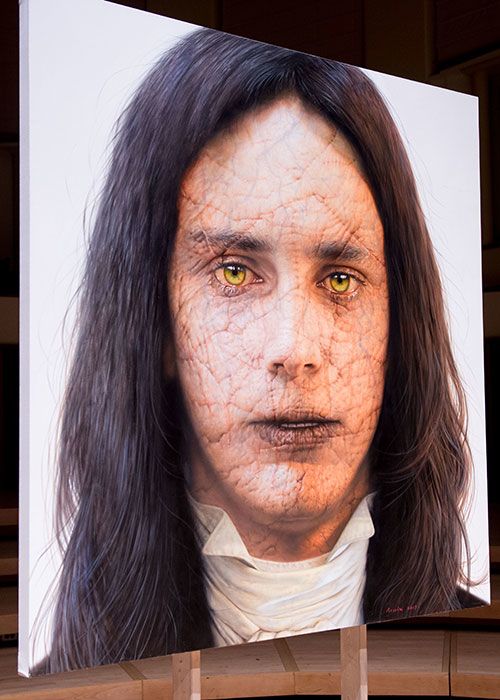

A large-scale interpretive portrait of Victor Frankenstein's creation by artist Ross Rossin is on display at Emory's Schwartz Center for Performing Arts. The painting was commissioned by FACE (Frankenstein Anniversary Celebration at Emory), which is featuring lectures, film screenings and other events throughout the year. On Tuesday, March 27, Rossin will take part in a Rosemary McGee Creativity Conversation, titled "Ultimately Human," with Andrew Young — pastor, diplomat, mayor and civil rights leader — at 7 p.m. at the Schwartz Center.

While the novel is an early, groundbreaking example of science fiction, it cuts across genres. Major questions raised in its pages about science, society and philosophy are still hotly debated.

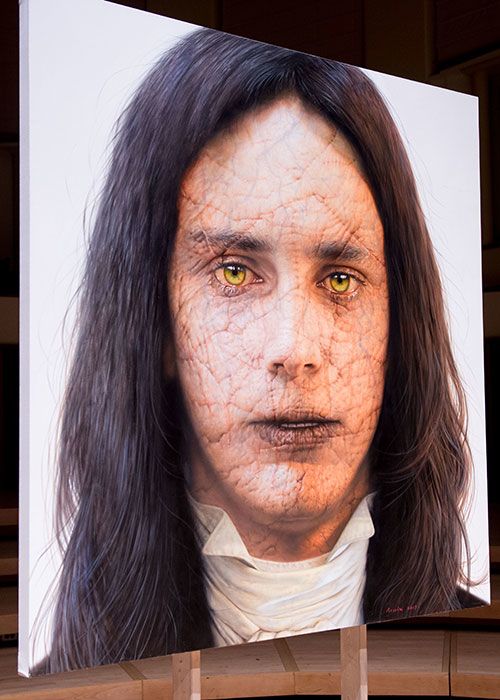

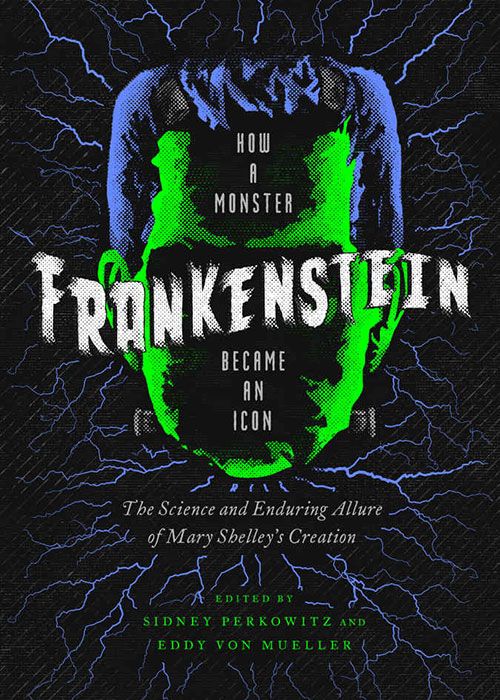

Emory faculty explore many of them in a newly published anthology,“Frankenstein: How a Monster Became an Icon, the Science and Enduring Allure of Mary Shelley’s Creation” (Pegasus Books). The anthology is co-edited by Sidney Perkowitz, Emory emeritus professor of physics, and Eddy Von Mueller, a former Emory professor of film studies who is now an independent filmmaker. They gathered chapters from 17 experts across the country, including five from Emory, on different spheres of Frankenstein’s influence.

Emory faculty from a range of disciplines contributed to a new anthology on Frankenstein.

“Frankenstein is one of the richest novels ever written,” Perkowitz says. “It’s full of important messages, such as there ought to be a way to make sure that science and technology work for the good of humanity, not the bad.”

Perkowitz contributed a chapter in the anthology on how “Frankenstein” relates to the current quest for synthetic life.

“When you see a contemporary film about androids, like ‘Blade Runner 2049,’ you’re seeing the ‘Frankenstein’ story in a 21st-century guise,” he says. “The androids are sleek and modern instead of the shambling, stitched-together creature in ‘Frankenstein,’ but they have the same questions swirling around them. Even as we’re on the verge of artificially generating life, we’re no closer to knowing whether we should.”

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley came of age during the Romantic Era, when relatively new discoveries such as electricity ignited curiosity and the line between the humanities and the sciences had not been drawn, notes Courtney Chartier, head of research services for Emory's Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, which has an original edition of "Frankenstein." Shelley's husband, the poet Percy Shelley, ran experiments in their home with an array of odd devices, such as what his friend and biographer Thomas Jefferson Hogg described as “an electrical apparatus.” The poet would stand on the device and tell Hogg to crank up the machine “until he was filled with the fluid, so that his long, wild locks bristled and stood on end.”

Mary Shelley, shown here later in life, was just 18 when she began writing "Frankenstein."

The couple was staying with friends in a villa in Italy when one member of the group — the poet Lord Byron — suggested that they have a competition to see who could write the best horror story.

Byron probably never suspected that the young Mary Shelley would win.

“She was just 18 when she began writing ‘Frankenstein,’” Perkowitz says. “As an Emory professor emeritus who has taught many exceptionally smart and creative students, I’m stunned that someone of college freshman age produced this powerful work that has endured for 200 years and still speaks to us today. That’s almost more remarkable than the ‘Frankenstein’ book itself.”

The vigor and timeliness of the book is reflected in its myriad themes, from the first famous “deadbeat Dad,” in the form of the monster's creator Victor Frankenstein, to the religious and feminist overtones of a man trying to usurp the power of God and of women to create life on his own. Some see the book as a commentary on mistreatment of “the other,” such as those with disabilities or anyone who differs from the mainstream.

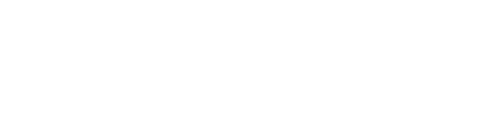

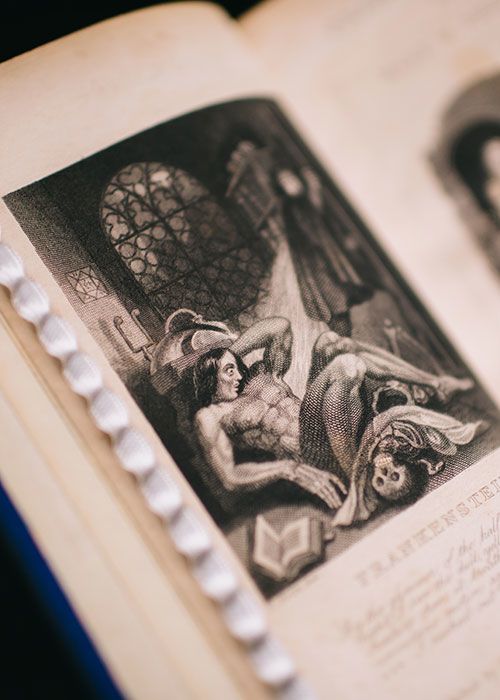

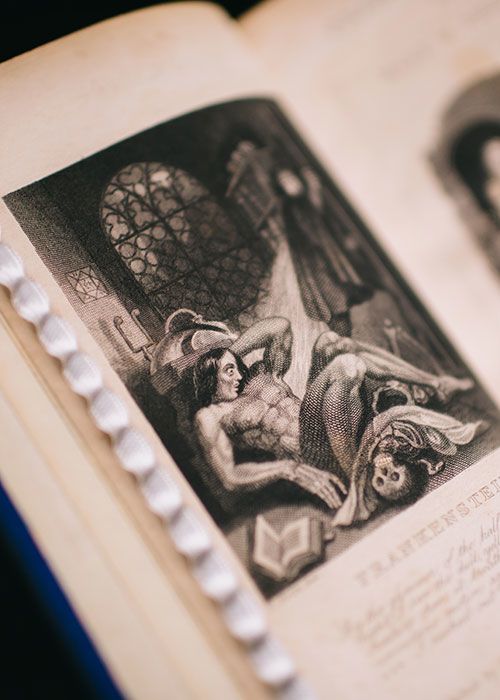

An 1831 copy of "Frankenstein" in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library features an early depiction of the "creature" and a prologue by Mary Shelley. She explains how she was inspired by the work of Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin's grandfather, and many others. (Photo by Stephen Nowland, Emory Photo/Video)

“What was kind of delightful as we were talking to people from all these different disciplines to create the anthology is how ‘Frankenstein’ becomes a meeting ground,” Von Mueller told WABE in a recent interview. “It’s really a nexus at which all of these distinctions dissolve and we can come together to talk about this one story.”

Chemistry professor David Lynn writes about how his own work, to uncover the molecular basis of life, echoes ideas expressed in Frankenstein. Steven Kraftchick, a professor at Emory's Candler School of Theology, takes on the question, what is a monster? Emory English professor Catherine Ross Nickerson describes the origins of the novel, while Laura Otis, also from the English department, reviews how Shelley’s novel depicts the emotions of an unwanted being in a way that few writers have matched.

Following are excerpts from each of their chapters.

Emory faculty from a range of disciplines contributed to a new anthology on Frankenstein.

Emory faculty from a range of disciplines contributed to a new anthology on Frankenstein.

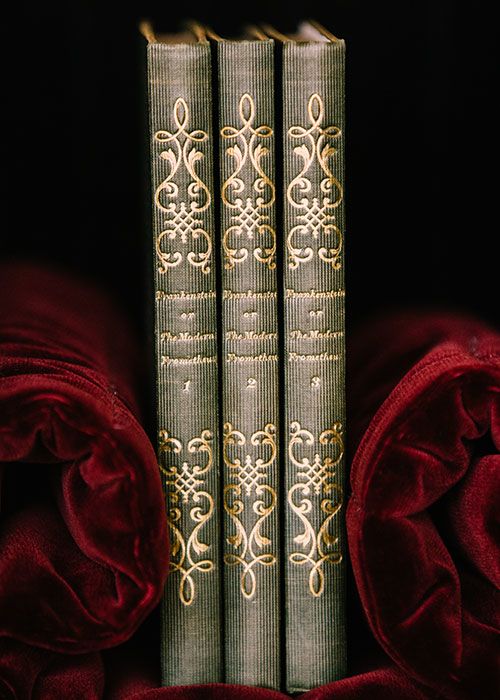

A copy of the 1818 original novel "Frankenstein" resides in Emory's Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library. It was first published anonymously as a "triple decker," or serialization of slim, separately bound segments of the story. (Photo by Stephen Nowland, Emory Photo/Video)

A copy of the 1818 original novel "Frankenstein" resides in Emory's Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library. It was first published anonymously as a "triple decker," or serialization of slim, separately bound segments of the story. (Photo by Stephen Nowland, Emory Photo/Video)

Mary Shelley, shown here later in life, was just 18 when she began writing "Frankenstein."

Mary Shelley, shown here later in life, was just 18 when she began writing "Frankenstein."

An 1831 copy of "Frankenstein" in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library features an early depiction of the "creature" and a prologue by Mary Shelley. She explains how she was inspired by the work of Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin's grandfather, and many others. (Photo by Stephen Nowland, Emory Photo/Video)

An 1831 copy of "Frankenstein" in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library features an early depiction of the "creature" and a prologue by Mary Shelley. She explains how she was inspired by the work of Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin's grandfather, and many others. (Photo by Stephen Nowland, Emory Photo/Video)

A large-scale interpretive portrait of Victor Frankenstein's creation by artist Ross Rossin is on display at Emory's Schwartz Center for Performing Arts. The painting was commissioned by FACE (Frankenstein Anniversary Celebration at Emory), which is featuring lectures, film screenings and other events throughout the year. On Tuesday, March 27, Rossin will take part in a Rosemary McGee Creativity Conversation, titled "Ultimately Human," with Andrew Young — pastor, diplomat, mayor and civil rights leader — at 7 p.m. at the Schwartz Center.

A large-scale interpretive portrait of Victor Frankenstein's creation by artist Ross Rossin is on display at Emory's Schwartz Center for Performing Arts. The painting was commissioned by FACE (Frankenstein Anniversary Celebration at Emory), which is featuring lectures, film screenings and other events throughout the year. On Tuesday, March 27, Rossin will take part in a Rosemary McGee Creativity Conversation, titled "Ultimately Human," with Andrew Young — pastor, diplomat, mayor and civil rights leader — at 7 p.m. at the Schwartz Center.

Chemistry professor David Lynn co-wrote a chapter called “What Would Mary Shelley Say Today?” with Jay Goodwin, from the MacArthur Foundation. An excerpt:

Shelley’s description of the scientist Victor Frankenstein, raising mortuaries and slaughterhouses for the materials for his Creature, conjures up graphic social images. A creature stitched from parts of multiple human and possibly animal parts, a patchwork quilt of skin, organs, and limbs most assuredly would have appeared uniquely grotesque to the naïve eye and repulsed even its creator.

We can see the faint echoes of this hybrid creature foreshadowing the emergent work in human/animal chimeric biology in present times, which is often branded as “Frankensteinian” in its pursuit and ethical implications.

Shelley also wove in origins-of-life themes, how to bring about life from inanimate matter, and the synthesis of a whole being by analogy, using component parts from different sources. These themes re-emerge today in the disciplines of systems and synthetic biology. While chemistry and electricity are both critical determinants of the genesis, function and reproduction of living matter, they in turn depend on the fundamental blueprints for life, ensconced at the molecular level, that underlie the central dogma of molecular biology.

Emeritus professor of physics Sidney Perkowitz wrote a chapter called "Frankenstein and Synthetic Life: Fiction, Science and Ethics." An excerpt:

In reality, making synthetic life is both science and fiction and even science and myth, with roots far older than this century or the 19th, when Shelley wrote. She understood this, for the full title of her story is “Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus.” In Greek mythology, Prometheus was a Titan, one of the powerful divinities who preceded Zeus and the other Olympian gods. In some versions of the myth Prometheus creates mankind, and in all versions he steals fire from the Olympians for the benefit of humanity. These actions angered Zeus, who punished Prometheus by sentencing him to eternal torment.

In Mary Shelley’s novel, Victor Frankenstein creates a living being with the hope of creating a superior version of humanity, but like Prometheus, he pays a price for his aspirations. Stories like these raise timeless issues and express significant truths. At the deepest level, they reflect our own feelings about life and death. Furthermore, they present the long-standing moral questions that synthetic life would raise. A modern scientist could still share the same goals and fears as Victor Frankenstein, but with one great difference: Now we truly have the scientific tools to modify and perhaps even create living beings.

Steven J. Kraftchick, a professor at Candler School of Theology, wrote a chapter called "Who is a Monster, When?" An excerpt:

The English term “monster” (by way of French) likely derives from the Latin words montrare “to demonstrate” and monere “to warn.” In effect,“monsters” demonstrate or warn; their presence attempts to make “something” evident. But of course, this raises the question of what, exactly that “something” is. And, once we are here, we see that “monsters” demonstrate only that they are phenomena that press the limits of the ordinary, expanding or contracting the usual and normal to a point of individual and social discomfort or rupture.

“Monsters” reveal not themselves but the limits of the ordinary and acceptable, as well as our inability to comprehend things that seem strange, unfamiliar, and discordant. We freely use the term “monster” in all sorts of settings: a monster deal at a store, a monstrous child, a monster truck, a monstrous ego, etc., thinking that we have identified an object or event, when, in actuality, we have simply pointed to its resistance to identification. Barbara Freeman suggests that this is what the monstrous does to all our attempts to define such terms, because by its very nature monstrosity defies definition, and the very attempt to do so demonstrates the limits of our language and our capacities to know and categorize ourselves and our surroundings.

English professor Laura Otis' chapter is called "Frankenstein: Representing the Emotions of Unwanted Creatures." An excerpt:

Mary Shelley’s novel, “Frankenstein,” depicts the emotions of an unwanted being in a way that can inform scientists and that few writers have matched. Accused of murder and bullied by her confessor, Shelley’s character Justine laments, “I almost began to think that I was the monster that he said I was.” Like Justine, scientist Victor Frankenstein’s abandoned creature sees himself as a monster — almost. One of the commonest words in Shelley’s text is “wretch,” used both by Frankenstein for the creature he has made and by the creature for himself. This double-edged word means both a “despicable person” and a “miserable person,” suggesting a vicious cycle. “All men hate the wretched,” says the creature, who feels wretched because he is unwanted and is unwanted because he is wretched.

The pain, gall, ice, fire and whirlwinds that represent his emotions reveal the forces acting on him, but also his fierce will to live. Shelley’s “Frankenstein” stands out among literary works for its sympathetic depiction of an unwanted being. Even though the creature’s rage and hatred lead to murder, Shelley represents his emotions as the products of natural and social forces that could work similarly on any deserted human being.

English professor Catherine Ross Nickerson's chapter is entitled "Hideous Progeny: Telling a Tale of Monsters in 'Frankenstein.'" An excerpt:

This book about unhallowed beginnings has its own famous origin story. Mary Shelley wrote the original version of the tale as an entertainment for a circle of artists and writers, including Lord Byron and her husband, Percy Shelley, on vacation in Italy in the summer of 1816. They were staying together in a large house, and it rained a great deal. To entertain themselves, they started reading ghost stories aloud in the evenings, and when they ran out of published stories, they proposed writing their own. Shelley’s first version of the story was created there, as a tale to be read aloud in a single evening.

She continued to work on it, expanding it into a novel over the next two years, and publishing it in 1818. Shelley revised it significantly for a new edition in 1831, adding an introduction that sheds light on her own understanding of the novel. The introduction also discusses her intellectual history and background. She was the daughter of two intellectual radicals, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, both of whom were involved in revolutionary movements in the late 18th century. The way that they had grappled with the troubling characteristics of British social order in the period — the sexism, the racism, the disenfranchisement of the middle and lower class — clearly influenced Shelley and shaped the narrative of “Frankenstein.”

Learn more about the Frankenstein Anniversary Celebration at Emory:

- FACE Calendar of Events — Spring 2018

- Rossin's Emory residency celebrates Ethics & the Arts, Frankenstein — Aug. 23, 2017

- Photos: Frankenstein's creation, unveiled — Sept. 27, 2017

- Andrew Young, Ross Rossin to be featured in March 27 conversation at Emory — March 19, 2018