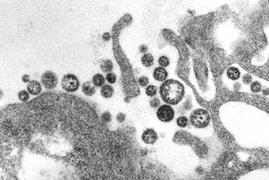

Lassa virus sample (photo from CDC library).

Lassa virus is thought to cause hundreds of thousands of infections each year in West Africa.

Two patients infected with Lassa virus in 2016 in West Africa were treated in Atlanta and Frankfurt, Germany with an experimental combination of the antiviral drugs ribavirin and favipiravir, doctors report.

The case report was published June 22, 2017 in Clinical Infectious Diseases. A companion article in Journal of Infectious Diseases describes the immune response to Lassa virus seen in one of the patients.

Ribavirin is the only medical countermeasure known to be effective against Lassa virus, which is estimated to infect 100,000 to 300,000 people per year in West Africa. Favipiravir is proposed to be active against several types of RNA viruses including influenza, and has also been tested against Ebola virus.

It is unclear whether favipiravir was critical for these patients' survival, says Colleen Kraft, MD, who is co-senior author of the CID paper together with Timo Wolf, MD, from University Hospital Frankfurt.

"Since favipiravir was reported to have a low side-effect profile in treating Ebola virus disease, we added it for Lassa treatment since we did not know whether our patients' conditions would worsen," she says. "We don't think that favipiravir caused any major side effects, but we cannot say anything conclusive on efficacy."

Kraft is associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine and medicine (infectious diseases) at Emory University School of Medicine. The patients were treated at Emory University Hospital's Serious Communicable Diseases Unit and at University Hospital Frankfurt's isolation unit.

The mortality rate from Lassa virus infection is estimated at one percent overall, but it rises to 15-20 percent with severe cases requiring hospitalization, and ribavirin treatment, if begun early enough, has been shown to substantially reduce mortality.

If later shown to be effective, favipiravir could be another option for treatment of Lassa fever in West Africa, Kraft says. In contrast to ribavirin, usually only available orally in resource-limited settings but ideally delivered intravenously, favipiravir can be delivered orally.

Both patients' infections resulted from contact with the same individual at a missionary hospital in Togo, who died from Lassa fever after evacuation to Germany. One of the patients, who provided nursing care to the person in Togo who later died, was evacuated to Emory eight days after becoming sick. The patient's suspected Lassa fever infection was verified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) upon admission to Emory University Hospital. The other patient, a mortician who handled the body, was evacuated to Frankfurt after doctors had confirmed his Lassa infection in Togo.

The patients experienced symptoms including fever, sore throat, cough, headache, weakness, muscle and joint pain, diarrhea and hearing problems. The Atlanta patient was discharged after 25 days and the Frankfurt patient was discharged after 39 days.

For both patients, favipravir treatment was stopped after five days because of nausea and elevated transaminase, a sign of possible liver damage, although the authors write that elevated transaminase may have been due to the viral infection. Also, in the Frankfurt patient, atrial fibrillation, a common cardiac arrhythmia, appeared during favipiravir treatment and disappeared afterwards.

Immunology

In the patients' body fluids, such as blood, semen, saliva and urine, researchers looked for infectious virus, viral RNA, and antibodies generated against the virus. This is how they were able to track how long the virus lasted in the body.

In the patient treated at Emory, researchers observed that the virus was undetectablie in the blood around 20 days after symptom onset. However, some immune cell responses, especially the CD8 T cells, lasted for several days more. In this later phase, the patient experienced symptoms such as swollen lymph nodes and inflammation of the epididymis, a coiled tube near the testicles that stores and carries sperm.

Lassa virus is carried by rodents in West Africa, and most infections are thought to come from contact with rodents or contamination with the rodents' droppings or urine, rather than human-to-human contact. Still, because Lassa virus was detectable in the patients' semen for several weeks after recovery, sexual transmission should be considered possible, the authors write.

Lead author Anita McElroy, MD, PhD, and colleagues including Emory scientists Rama Akondy, PhD and Ali Ellebedy, PhD reported the immunology results in detail in the JID paper. McElroy is affiliated with Emory and the CDC. Research on patient samples was conducted at Biosafety Level 4 facilities at the CDC in Atlanta, and the Institute of Virology at Philipps University Marburg in Germany.

The co-first authors of the CID paper are infectious disease fellow Vanessa Raabe, MD from Emory and Gerrit Kann, MD from Frankfurt. Additional authors from Emory include Bruce Ribner, MD, MPH, Jay Varkey MD, Aneesh Mehta, MD, G. Marshall Lyon, MD and Sharon Vanairsdale, RN. Other authors come from Hospital of Hope in Togo, Samaritan's Purse, CDC and the Institute of Virology in Marburg.

Favipiravir was obtained from Medivector; the U.S. Food and Drug Administration provided emergency investigational new drug approval.