The darkest day of Marjorie Stowe's depression came when her long-time psychiatrist told her she obviously was choosing to resist the healing effects of one medication after another, psychotherapy, electric shock. "You must be getting some emotional payoff that prevents you from letting your depression go," he said. "Secretly, you must enjoy being this way."

What's left when your own psychiatrist gives up on you? During the day, praying helped her hold on. At night, she prayed not to wake up.

Growing up in Franklin Springs, Georgia, the youngest of a Pentecostal minister's six children, Stowe was a serious, unsmiling child. She graduated from hometown Emmanuel College, took pre-pharmacy courses at the University of Hawaii, and earned a PharmD from Campbell University in North Carolina. She managed it all — school, then work and marriage — with the help of antidepressants.

Her plunge into suicidal darkness began at 39, after the birth of her daughter. Could it be hormonal? Her gynecologist shook her head, then told Stowe about an Emory neurologist named Helen Mayberg she had just read about, who was doing a special type of brain surgery with electrodes for treatment-resistant depression, with promising results. You have a physical illness of the brain, the gynecologist said. This might be your best hope.

Fifteen percent of Americans have clinical depression during some portion of their lives. A third of those have major depression: suicidal thoughts, a sense of disconnection from the world. For a few of those, the entire arsenal of traditional treatments — therapy, medications, even electroconvulsive therapy — doesn't work. These are the patients Mayberg sees.

Stowe was a model case. Indeed, her long-term depression was so severe, it made it difficult for her to gather the required documentation and go through the long psychiatric interviews.

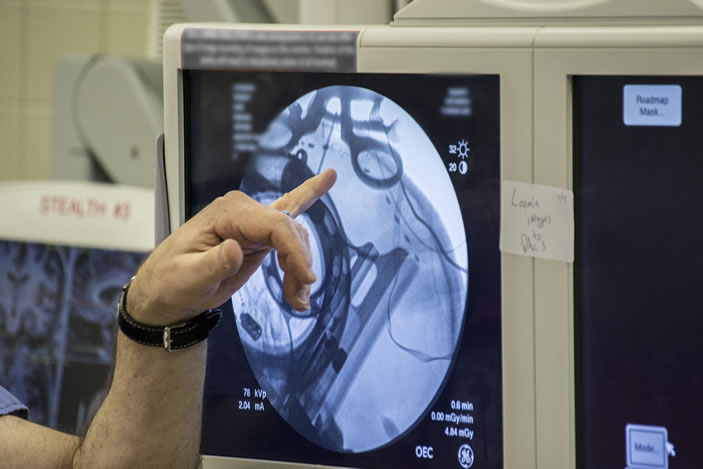

The day of surgery, Emory neurosurgeon Robert Gross implanted very thin wires with tiny electrodes in two small lobes deep at the midline of Stowe's brain.

Mayberg stood beside Gross, quietly talking to Stowe, guiding her through the process as she often does with patients. Gross was the surgeon, Mayberg the architect and team leader. Precisely where Gross placed the electrodes was based on Mayberg's extensive brain maps, both of activity in different regions of the brains of depressed patients and of the neural cables that connect these regions, allowing communication between them. Stowe was awake to report any sensations when the electrodes were activated. (It's not as bad as it sounds, since the brain has no pain receptors.)

The electrodes' job is to deliver a small amount of electrical current to the specific region of the brain Mayberg discovered is overactive in people with depression. This region, Area 25, serves as a kind of junction box, so adjusting activity here is like tuning the entire depression circuitry. The electrodes are connected to an implantable pulse generator (IPG), a pacemaker-like device placed under Stowe's collarbone. The IPG keeps a steady stream of low voltage flowing into the patient's brain.

As the electrodes are tested in the OR, patients often report an emotional weight being lifted instantaneously—one way the team knows the electrode is in the right place. Within a week after surgery, with the electrical current flowing continuously, Stowe began to notice sunlight, birdsong. Her sense of humor returned. Her boss didn't recognize her on the phone, so changed was her voice.

Two years later, Stowe says the procedure has been transformative. "It brought me out of the pit," she says. "People who haven't been there can't understand what a gift it is to feel joy. I always loved my family. Now I enjoy them."

Her 5-year-old daughter, Maddie, doesn't remember the mommy who cried every day, only the happy one involved in her life. They enjoy horseback riding, playing in the park, and getting mani-pedis on girls' days out. Before deep brain stimulation (DBS), Stowe felt completely dependent on her husband, Jeff, a Home Depot project manager. After the procedure, she feels like an equal partner—and it's fun, she says: "Laughing like we used to, motorcycles, camping, Georgia Tech football, happy times with my daughter and stepsons, Joshua, Sean, and Zachary."

She recently started training for a 5-K race, determined to be as healthy physically as she now feels mentally. Jeff refers to her as "the new and improved version."

This major shift in mood and energy level took some getting used to, however. "After 30 years in a kind of prison, it was a big adjustment to suddenly be well," says Stowe. "I didn't know what to do, what to feel." The research team's responsibility doesn't end in the OR, says Mayberg. Stowe receives ongoing treatment from behavioral therapist Cynthia Romero, psychiatrist Patricio Riva Pose, and the rest of the DBS research team.

Now that Stowe's brain is able to focus, thanks to the "reset" of DBS, she is learning to enjoy the moment, to not dread the future, and — hardest of all, she says — to let go of the guilt about what her family went through during her illness.