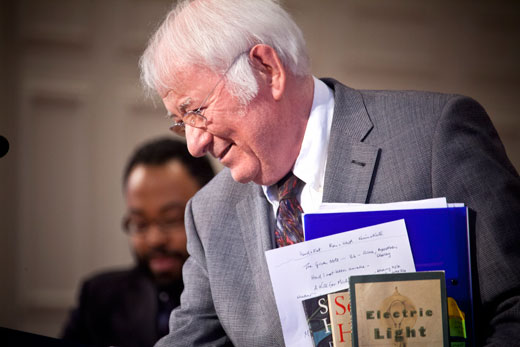

Acclaimed Irish poet Seamus Heaney's March 2 talk at Emory was not so much a reading as a recitation. The Nobel Laureate quoted his poems from memory, referring to the printed page occasionally and putting them in the context of their history, inspiration and creation.

Heaney visited and spoke as part of the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library Reading Series. The series is sponsored by Emory's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL), where a large portion of Heaney's papers reside.

The poems and corresponding stories Heaney shared during the hour he spoke to a full house in Glenn Memorial Auditorium included:

"The Given Note": The Celtic fiddle music played before Heaney's talk prompted the poet to read from and talk about this poem, based on a traditional story from the south of Ireland called "the Tune of the Spirits" about a melody that arrives out of the air. Heaney's fiddler heard "strange noises... bits of a tune / Coming in on loud weather…/The house throbbed like his full violin."

"A Kite for Michael and Christopher": "More wind," Heaney said, segueing into a poem about kites written in the 1970s. Although the poem was for his two boys, Michael and Christopher, Heaney said the inspiration was his own childhood "when my father flew a kite once upon a time. It almost had a fairy-tale effect for us because he wasn't devoted to kite-flying." He described that kite of his childhood as a not being a "nylon flimsy" but a huge one made out of newspapers and paste and sticks, "and it took a kind of small gale to lift it."

"The Tollund Man": A poem about the 4th century B.C. naturally mummified man found in Denmark, which Heaney called Jutland, in the 1950s. His body disintegrated in the air and light, Heaney said. "But they got the technology going in time to keep his head." Discussing the speculation of the Tollund Man's fate, Heaney said, "If he was sacrificed, he was sacrificed to bring back some kind of life to the Earth and to the community. That's what we desperately needed in the '70s in Belfast and the North," referring to the "Troubles" of Northern Ireland.

"Oysters": One of the great reliefs of getting away from all that shadow and gloom and danger was to go the west of Ireland, particularly to an oyster cottage as they call it down in County Galway, Heaney said. He described how the light comes up off the Atlantic Ocean. "[The poem] is also about a kind of promise that is in artwork and a kind of hope that it might embody. "

"The Harvest Bow": This poem, Heaney said, is about a rural artifact made by farmers years ago. "My father used to make them at harvest time from plaited wheat straw and wore on his lapel." He referenced a school of thought linking it to an Indo-European spirit of the corn ritual.

"The Baler": "This is another harvest title," Heaney said, "the hay baler at work." He noted that when he was growing up, he was a "pre-baler, a fork and rake man."

This poem, he said, "moved from the field to the table of our house some sad evening."

"Two Lorries": Heaney had written about two lorries (trucks), one delivering coal to a farmhouse in the country in the 1940s and the other hijacked by presumably the provisional IRA to deliver a proxy bomb, which blew up the center of a small town, he said.

"At the Wellhead": Heaney noted that this poem "does have the age-old trope of the blind singer being the archetype of kind of utterance." The poem's subject is linked to a blind neighbor of his family's.

"Miracle": Heaney used the context of this poem, based on a New Testament miracle in which a paralyzed man is lowered through a roof to Christ for healing, to talk about his brush with a stroke. In both cases, he noted how the positive action could not have occurred without the help of friends.

"Poet to Blacksmith": In reading this one, he said, "I'm sorry I haven't got the Irish to speak to you or read to you but I assure it exists in the mother tongue... It reminds me of my blacksmith neighbor. When I was growing up, he was shoeing horses and now that he's in his late 80s, he's inviting people in to see the forge and say to people that this is the forge Heaney wrote about. In fact, he's on the 'net."

"Midnight Anvil": Heaney sketched a scene describing how the blacksmith on New Year's Eve at the millennium struck his anvil 12 times to ring in the New Year and the new millennium.

He concluded with two "ending" poems, one about birds, the sea and wind, and one about a kite for one of his grandchildren.