AIDS in Atlanta

Why the ‘public health capital of the world’ has such high rates of HIV/AIDS, and how researchers are trying to turn the tide.

THE YOUNG MAN had been getting treatment for AIDS at the Ponce de Leon Center in downtown Atlanta for some time, but suddenly he stopped showing up. His doctors weren’t sure why. Maybe he was depressed. Or ill with a related infection. Or he just couldn’t get a ride.

He finally did find his way back to the center, but by that time his AIDS had progressed. He died a few days later.

In metro Atlanta there are thousands of men just like him—young, black, gay or bisexual, and HIV positive. And an alarming number are progressing to AIDS and dying of a disease that has, for decades now, been treatable.

The city that is home to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one of the largest clinics for HIV/AIDS patient care in the country, and top-funded HIV research programs, is also an epicenter of the HIV epidemic in the U.S.

Some zip codes in the Atlanta area have rates of HIV/AIDS that are six- to eight-times higher than the national average. And by the time patients in Atlanta are diagnosed as HIV positive, about a quarter have AIDS, which means they have likely been living with the virus for eight to 10 years.

“Downtown Atlanta has a generalized HIV epidemic that mirrors what we see in some African cities,” says Carlos del Rio, Hubert Professor at Rollins School of Public Health and co-director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research (CFAR).

The reasons have more to do with poverty, lack of insurance, and stigma than with sexual practices. The high rates of HIV/AIDS are mostly confined to a specific group—young, black men who have sex with men. In fact, AIDS is the leading cause of death for black men in Georgia between the ages of 35 and 44.

These men don’t have more partners or indulge in riskier sexual behaviors than their white counterparts, according to studies at Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health. But they are more disadvantaged. They often lack insurance. They may not have transportation, so getting to a clinic can be a challenge.

And due to the stigma associated with their sexual orientation, many don’t have a support system of family and friends.

The result is that advances in drug treatments and care that have transformed HIV into a manageable chronic disease for many have been out of reach for this group.

“A lot of headlines talk about the end of AIDS, but there is a lot of slip between the cup and the lip when you have a population as vulnerable as ours is,” says Wendy Armstrong, an Emory professor of medicine and director of the Ponce de Leon Center, which is part of the Grady Health System and is staffed by Emory doctors. “These are people who are more worried about where they going to sleep or where they’re going to get their next meal than about getting their next HIV treatment.”

Curbing the HIV epidemic in this disenfranchised population will require more than developing better treatments and drugs.

“This is not something that is going to be solved by biomedical researchers,” says del Rio, chair of global health at Rollins. “We need everyone working together to address all the things that keep people from getting the diagnosis and treatment they need—lack of insurance, barriers to care, stigma, and poverty. Emory and our partners are making real progress in Atlanta, but we still have a long way to go.”

“We are reaching teens who are not yet sexually active to try to get them to adopt good habits,” says Patrick Sullivan, Rollins professor of epidemiology.

Overcoming stigma

Getting high-risk men to go in for testing has long been a high hurdle. Some just don’t realize HIV is still such a threat. Others may be in denial. And many do not want to be linked to homosexuality or bisexuality, IV drug use, or an HIV diagnosis.

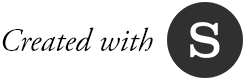

“There is tremendous stigma in many black communities around being gay or bisexual or having HIV,” says Patrick Sullivan, the Charles Howard Candler Professor of Epidemiology at Rollins and director of the school’s Programs, Research, and Innovation in Sexual Minority Health (PRISM). “Some of this is wrapped up in religion and in concepts of masculinity. We did a study about perceptions of stigma around being gay, and white men reported feeling less stigma associated with their sexuality than black men.”

One of Armstrong’s patients had moved out of his mother’s house to keep her from finding out about his HIV status. “He’s been staying in transient housing, dealing with bedbugs and fleas. He said if he were to tell his mom of his diagnosis, he’s afraid it would kill her,” she says.

To overcome obstacles to getting tested, Emory and its partners have been working to make HIV testing routine and free in a variety of sites. Grady Memorial Hospital began “opt-out” HIV testing in its emergency room—you check a box if you don’t want to be tested. This testing often results in one to two new diagnoses a day and has since been expanded to 13 sites, including primary care and neighborhood clinics.

“I’m really passionate about screening patients for HIV,” says Emory emergency medicine physician Bijal Shah. “In 2006, the CDC actually recommended that all patients in acute care settings ages 13 to 64 be tested for HIV, regardless of their chief complaint or risk profile. I had the opportunity to make routine HIV testing part of what we do every day at Grady. I’m proud to say we’ve tested more than 80,000 patients and made more than 500 new HIV diagnoses.”

Rollins physician-researcher Anne Spaulding believes that jails are another place where voluntary screenings could have a large impact. Inmates in Atlanta’s Fulton County Jail are predominantly young (median age 33), male (71 percent), and black (87 percent)—a close match to the high-risk HIV population. Spaulding piloted the use of a voluntary, rapid HIV testing regimen as part of the medical intake process at the jail.

Inmates who tested positive were quickly started on treatment—often before they even left jail. “This was not about detecting HIV/AIDS cases newly acquired within jails,” says Spaulding. “This was about making sure previously infected people didn’t leave jails unaware that they were positive and inadvertently spread the infection.”

Fulton County has since suspended the rapid HIV testing program, even though it was successful. The move disappointed many and underscores the belief that Atlanta could do more to expand routine HIV testing.

“We could take a page from other cities’ playbooks,” says Sullivan. “In D.C., you can get an HIV test at the Department of Motor Vehicles. In London, there are self-service kiosks for testing. New York, San Francisco, and Boston are all more aggressive in their fight against AIDS than Atlanta has been.”

Streamlining the process

Testing is just the first step. Patients then have to get into treatment, a process that can be slow and challenging even for those fortunate enough to have insurance. Those without insurance rely on the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program to cover their medical care and support services. Enrolling requires assembling a daunting set of documents—a task that can prove virtually impossible for a person without transportation or a permanent address.

A couple of years ago, Fulton County created a task force to curb AIDS, which included Emory clinicians as well as other local health care providers, people living with AIDS, community advocates, and others. The group set an ambitious goal of getting newly diagnosed patients into treatment within 72 hours.

Toward that end, the local Ryan White program relaxed the time frame required to submit documentation for eligibility.

Then the physician leadership at the Ponce Center led an effort to restructure the admission system and reworked doctors’ schedules. The streamlined process worked so well that the facility was quickly overwhelmed.

“We got more new patients in six weeks than we normally get in a year,” says Armstrong. “We can treat our way out of this epidemic if we can get people into care.”

Keeping them well

Making sure that patients keep taking their medications can be a job in itself, according to Atlanta physician Melanie Thompson, an Emory School of Medicine alumna and chair of the HIV Medicine Association.

She tells of one of her patients who worked a manual labor job with no health benefits, slept on friends’ couches, and relied on others to bring him to appointments.

Thompson and her staff worked out a system to keep close track of his medicine refills, calling to remind him when his medicine was going to run out and when he was scheduled for appointments.

“To keep this man in care, we have to do an awful lot of hand-holding,” says Thompson.

“And that is just the reality. In some sense, the easy job has been done. People who have insurance and more stable lives are doing really well. But it’s going to take a lot more energy and resources to help those who have more complex lives.”

Avoiding infection

HIV-negative men can avoid infection, even when they couple with positive partners, thanks to an extremely effective pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) marketed under the brand name Truvada, which contains the Emory-developed drug Emtriva. The problem for some is finding where to get it.

Rollins researchers developed the PrEP Locator, the first searchable national database of clinics that prescribe PrEP.

For Rick Perera, an Atlanta man who has been on PrEP for several years, the locator’s ability to identify which providers have PrEP navigators—people who can help clients through the labyrinth of requirements and forms—is especially valuable.

“It is a lot to take on,” says Perera. “In addition to the medication itself, you have quarterly office visits and testing. Insurance might pay for some or all of it. Financial assistance is available. But wading through all the paperwork that is required can be very hard. Being able to find a PrEP navigator is a tremendous service.”

The PrEP Locator has been useful in highlighting where providers are not available, as well.

“We discovered there is just one PrEP provider south of I-20, even though that is where most of the risk and the HIV cases are,” says Sullivan. “Until you know where the services are being provided, you can’t know where the gaps are.”

The Rollins PRISM program has developed a variety of tools and apps aimed at preventing infection and initiating treatment. One app being tested is aimed at 13- to 18-year-olds. “We are reaching teens who are not yet sexually active to try to get them to adopt good habits,” says Sullivan. “This type of technology can reach young people where they are—which is on their phones.”

Carlos del Rio, chair of the Rollins Hubert Department of Global Health, is co-director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research.

Carlos del Rio, chair of the Rollins Hubert Department of Global Health, is co-director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research.

Wendy Armstrong is an Emory professor of medicine and director of the Ponce de Leon Center, which provides services to about 6,200 people in the area living with HIV/AIDS.

Wendy Armstrong is an Emory professor of medicine and director of the Ponce de Leon Center, which provides services to about 6,200 people in the area living with HIV/AIDS.

Rollins epidemiologist Patrick Sullivan directs the school's Programs, Research, and Innovation in Sexual Minority Health.

Rollins epidemiologist Patrick Sullivan directs the school's Programs, Research, and Innovation in Sexual Minority Health.

Reaching out

The strongest concentrations of HIV/AIDS cases in Georgia are found in Fulton, DeKalb, and Clayton counties. Metro Atlanta has the fourth-highest HIV rate of major U.S. cities.

Finding and helping the people these statistics represent can be daunting. “There is still a lot of work that needs to be done here, but we are finally lining up everyone to work together,” says del Rio.

A case in point: researchers at Rollins, the University of Houston, and the Southern AIDS Coalition are establishing a center for a new 10-year, $100 million initiative by Gilead Sciences, through which they will map service providers and areas of need across the South.

“A lot of smaller organizations have strong connections in the community, but they may not have the resources to compete for grants or access to the latest training and technology,” says Neena Smith-Bankhead, a Rollins program director. “We want to work with them to build their capacity to better serve and care for those with HIV in their own communities.” EHD

To support the Center for AIDS Research at Emory, contact Ashley Michaud, senior director of development, at 404.778.1250 or ashleymichaud@emory.edu.