In 2004, the Baghdad Airport Road was a vulnerable conduit, a sweeping stretch of pavement that linked the city’s heavily fortified Green Zone — the town's governmental and military core — to the Baghdad International Airport.

To enter or leave the city, you first had to survive Airport Road, a favorite target for lookouts and snipers, rocket-propelled grenades, vehicle-borne suicide bombers and improvised explosive devices.

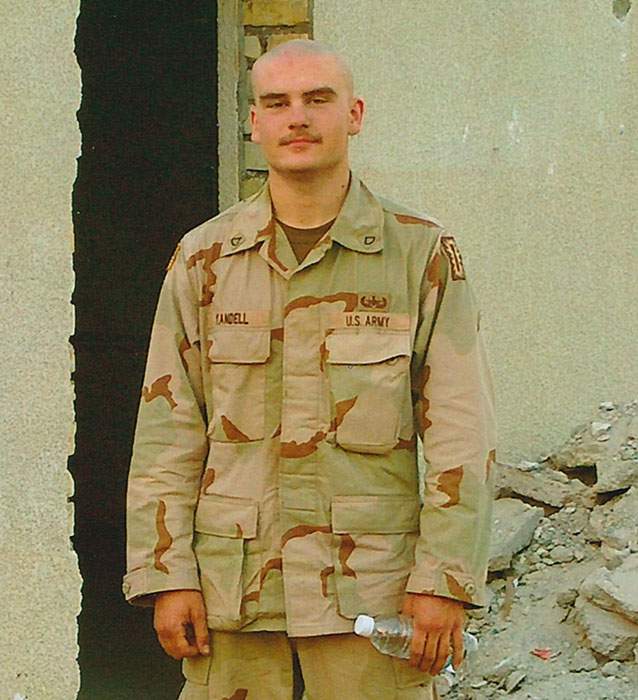

For 19-year-old Pfc. Michael Yandell, a bomb disposal technician for the U.S. Army, neutralizing ordnance was another day at the office, albeit a treacherous one. Over a few months, it wasn't uncommon to see dozens of attempted bombings along the highway.

Following the 2003 invasion of Iraq by U.S. and coalition forces, the road earned many nicknames. As a main artery for supplies, the U.S. military called it "Route Irish." As a frequent point of insurgent attacks, journalists simply dubbed it "the most dangerous road in Iraq."

But for Yandell, now a theological studies PhD student in the Graduate Division of Religion at Emory's Laney Graduate School, experiences along that road — and points beyond — would become a seedbed for scholarship.

Last fall, Emory hosted a symposium through Candler School of Theology's Laney Legacy in Moral Leadership program to explore the concept of "moral injury," the emotional and spiritual pain that can afflict those ordered to act against their own moral beliefs — essentially, a wounding of the soul.

According to information published by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, "the key precondition for moral injury is an act of transgression, which shatters moral and ethical expectations that are rooted in religious or spiritual beliefs, or culture-based, organizational and group-based rules about fairness, the value of life, and so forth."

Across disciplines, it is a rapidly growing field of scholarship, garnering media attention from the New York Times and the Washington Post to military-oriented publications like Stars and Stripes and the Military Times. And for Yandell, it is also deeply personal.

In fact, the earliest threads of his interest arise from his own past, taking root within the raw, morally ambiguous landscape of the Iraq War — imbued with ancient cultures, hidden explosives and complex choices.

His scholarship has provoked a challenging, and at times uncomfortable, exercise in self-examination.

And within it, an ongoing search for both reconciliation and redemption.

Pfc. Michael Yandell in Baghdad in 2004

Part 1: Danger and duty

May 15, 2004 — The call came early, as the sun was beginning to paint a stripe of warm, orange light across the desert horizon: Explosion on Route Irish. Possible secondary device.

For Yandell and then-Staff Sgt.James Burns, of the 752nd Explosive Ordnance Disposal Company, such investigations were routine. Fueled by the daily adrenaline of the call, they reported to the scene.

One IED had already exploded near Baghdad's Yarmouk neighborhood, but reports indicated a secondary projectile in the roadway. Yandell and his team leader sent a camera-loaded robot to investigate. Peering at a control screen from a distance, they studied what appeared to be a cracked, rusted-out 155-millimeter shell.

The original blast had detonated near an American patrol without injuries. Initially, they suspected this was a secondary device that had fizzled.

Iraqi militants often recycled abandoned artillery shell casings. To circumvent that, Yandell and his company destroyed them. But rather than risk prolonged sniper exposure at the scene, they opted to retrieve this one for disposal back at the base.

Cradling the hefty, 25-inch-long round, Yandell placed it in the truck bed and slid into the driver's seat. Within minutes, both soldiers felt something was wrong.

Burns would later report a strange, bitter smell and the surge of a crushing headache. Yandell's head was pounding, too, amid a cloud of confusion. The sun seemed too bright. His vision blurred. It was a struggle to even see the road.

By the time they reached camp, the shell was leaking liquid. Burns told Yandell to wash off, suspecting they had just ferried a chemical agent onto the base.

Yandell already knew. Staring into a mirror, he couldn’t see his pupils, which had constricted to faint pinpoints. "The classic sign of nerve agent exposure," he recalls.

What happened next remains hazy. He remembers being rushed to a clinic, tended by medics in protective gear.

"To be a good soldier, I had to be in control," says Yandell, who described his experience in an interview with NPR's StoryCorps. "Sarin proved to me I had no control."

The shell was later determined to be a rare binary chemical weapon, bearing twin containers of chemical precursors intended to mix together when fired to form sarin, a banned nerve agent considered lethal in even modest concentrations.

If not for the fact that the shell was quite old — likely left from the Iraq-Iran War in the 1980s — and the chemicals hadn't mixed properly, Yandell might have faced a swift death.

While coalition troops never would find an active weapons of mass destruction program in Iraq, they did discover hidden caches of degraded chemical weapons, many created 20 years earlier.

According to a 2014 New York Times investigation into the impact of Iraq's aging arsenal of abandoned chemical weapons, Yandell was among hundreds of American service members exposed to the remnants of those chemical munitions between 2004 and 2011.

In fact, one retired Army neurologist quoted by the Times believes Yandell and Burns may represent the first documented battlefield exposures to a nerve agent in U.S. history. Ten days later, they received Purple Heart medals, an honor presented to those wounded or killed in the line of service.

It would be years before Yandell fully understood the depth of his wounds.

Part 2: Becoming a soldier

Sitting in a local coffee shop, Yandell gazes out on a sunny day, considering the future, reckoning with the past. More than a decade stands between him and Iraq, but he still grapples with the war — the point of it, his role in it.

A PhD student who completed his comprehensive exams in the fall, he's now an ordained minister immersed in theological studies at Emory’s Laney Graduate School, with the support of a Laney Fellowship. He looks forward to an academic life, with hopes of teaching at the college level.

He has published reflections on his Iraq experiences in Christian publications Plough and Christian Century, and he has an essay included in "Exploring Moral Injury in Sacred Texts" (Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2017) — the only chapter in the book written by a scholar who is not already a professor.

His wife, Amy Yandell, works for the American Academy of Religion at Emory's Luce Center. They are building a good life, filled with wonderfully ordinary things. A beagle. A high school exchange student. A mortgage.

Yet the past tugs at him. Perhaps it always will.

Once a soldier, he now looks back with a scholar's eyes. He's not anti-military. Nor does he assume anyone's experience mirrors his own. But these days, Yandell has the time and space to be contemplative about the personal costs of war. The disillusionment. The regret. The never-ending quest to make sense of it.

He doesn't claim to have answers, only to know that "there is a certain kind of hubris in saying we are going forth to defend freedom and know exactly what the result will be."

Tattoos meander across his forearms, the back of his hands, his throat — all Christian symbols, deliberately chosen. Across his back, beneath a buttoned-up shirt, hides a classic Superman emblem. The bold body art contrasts with a boyish grin and gentle, rumbling voice.

Reflecting on his wartime experience, Yandell acknowledges that chemical weapons are their own form of horror. But then, so are conventional weapons.

"There is a deep inhumanity undergirding the technical drive to make better, more efficient killing devices," he says. "It's revolting to me, in the same way that a lot of other weapons are revolting. Landmines. Cluster bombs. There's no way to avoid civilian casualties. A kid gets their leg blown off. Better or worse than a chemical weapon, it's all pretty horrific."

Yandell remembers the day he chose the military. The morning of Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2001, he was in an economics class at Union City High School in northwestern Tennessee.

Who knew what the future held. Maybe he would work in a comic book store.

But that morning, a television screen that normally scrolled the stock market ticker-tape was interrupted with images from New York's World Trade Center. Yandell felt his emotions cycle from shock to indignation and outrage.

Within days, he was talking to a U.S. Army recruiter. "It wasn't so much a sense of duty that drove me, as it was a teen feeling invulnerable," he reflects. "I was going to do amazing things across the world."

Michael Yandell was inspired to join the military by the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

After graduation, he reported for basic training. His test scores allowed him a choice of specialties; he chose Explosive Ordnance Disposal.

Simply put, his job was to render explosives safe. Beyond the danger, it emphasized the protection of lives, which appealed to him. Following training, Yandell was stationed at the Army's Pine Bluff Arsenal, in Arkansas. It felt good to be a part of something bigger than himself, to have a mission.

Growing up, Yandell had always loved superheroes — especially Superman and the X-Men, heroic mutants born with special powers who fight for peace and equality. In comic books, there was moral clarity; it was easy to tell the good guys from the bad guys.

Deploying to Iraq in February 2004, Yandell traded a world that made sense, "where violence and killing were acts to be punished, understood to be wrong," for a world where all bets were off. "I was a willing participant in the war, because I understood that the so-called enemy was evil," he recalls, flatly.

By the time Yandell arrived to serve in Operation Iraqi Freedom II, President George W. Bush had already declared "mission accomplished."

To Yandell, it was clear that things were just getting started.

Part 3: Starting to question

In Iraq, danger was a given. IEDs were proliferating, and larger military objectives seemed to constantly shift. There was little time for soul-searching and reflection.

Down time was spent in escape — working out, listening to heavy metal music, playing cards. Raised in the Disciples of Christ church, Yandell hadn't defined his own faith practice. But wherever he went, he carried a copy of the Gideons' New Testament in his pocket and found a way to church services.

"The biggest benefit was immediately finding yourself in a place that is familiar. That's important when you're single and alone,” he says. "At a church, you feel at home."

Yandell often heard religious language woven into talk of defending freedom, along with entrenched stereotypes of exactly who were the enemies and who were the good guys.

Reality was more complex. He met Iraqis grateful for his presence, but also those who feared and resented him.

"It was definitely easy to demonize, to dehumanize everyone in the Middle East as people who would execute terrorist acts — it all became conflated. You didn't necessarily think about the violence we were responsible for," he says.

While recovering from sarin exposure, Yandell watched the Abu Ghraib prison scandal unfolding in the news. Returning to duty, "I really lost all sense of confidence in myself as a soldier, a technician prepared for whatever was going on," he says. "The job just wasn't the same."

At the time, EOD specialists received six-month deployments; shorter stints meant to combat stress and burnout. Yandell returned to Arkansas, on the fast track to becoming a sergeant. After the life-and-death intensity of Iraq, "working a John Kerry rally at Disney World was just weird," he chuckles.

Yandell began to struggle. He suffered light sensitivity, couldn't sleep. He felt anxious. Unsettling memories crowded him, day and night. When his unit prepared to redeploy, Yandell wasn't cleared to join them. "It was not an easy couple of years," he recalls.

Following a parade of physicians and counselors, he amassed "a stack of paperwork of potential diagnoses," but little else. When he mentioned the sarin exposure, he felt skepticism.

In 2006, Yandell finally received a diagnosis that seemed to fit — bipolar disorder — along with a medical retirement. Back home, he enrolled at the University of Tennessee at Martin, about 10 miles from where he'd grown up, with plans to major in music education.

"I wanted to get as far away as I could from the life I'd just left behind and do something different," he says. "Teaching music to school children sounded completely different."

Early in his studies, Yandell recalls hearing a history professor speak on a panel about the Iraq War from an outsider’s perspective. "Seeing this guy, in a room filled with people hostile to his position, critically evaluate what had happened over there was eye-opening," he recalls.

He walked away understanding that you can question faith, belief and nationalism and not be against their underlying values. "To critique faith doesn't mean I'm unfaithful. To critique what my country has done doesn't mean I hate my country," he explains.

Seeking electives, Yandell signed up for a religious studies course called "God and Human Happiness." The class arose from the teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas and affirmed the idea that there had long been people "who asked the biggest, most profound questions about issues like human suffering and our very existence," Yandell recalls.

"That's not to say we ever get the answers right," he adds. "But the process of struggling with those questions in an honest way was exciting."

Within him, something was beginning to awaken.

Part 4: Finding a purpose

By fall 2012, Yandell had decided to pursue those big questions, enrolling at Texas Christian University's Brite Divinity School just as the seminary was launching a program arising from a relatively new field of study.

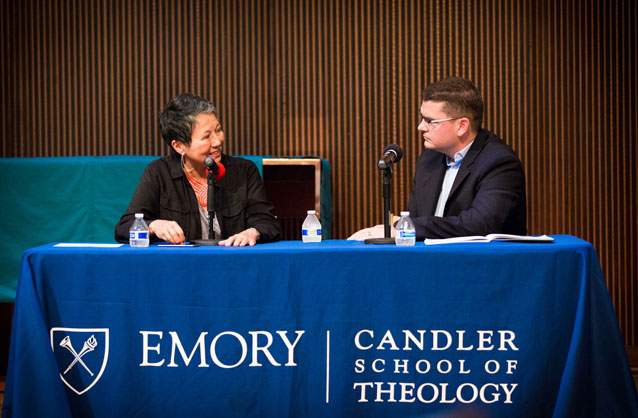

Co-founded by the Rev. Dr. Rita Nakashima Brock, the Soul Repair Center was dedicated to research into moral injury and how religious leaders could best support military veterans and their families. The more Yandell read, the more he identified with it.

"Moral injury results in a kind of schism between one's perceived moral self and one's actions," he explains. "When you recognize that you have failed to live by your own moral convictions — sort of a moral identity crisis."

Advanced by Jonathan Shay, a physician and clinical psychiatrist who worked with Vietnam veterans, the term described a betrayal of a person's moral values under a superior's authority in a high-stakes situation. For Yandell, the term resonated.

"For me, part of wanting to pursue a theological education was wrestling with questions of violence, suffering and evil," he says. "How do I take this experience of war — as absurd and insane as it seems — and give it meaning beyond suffering and chaos?"

As part of the center's launch, Brock asked Yandell if he would speak on a veterans' panel.

"Of course, at the time I had no idea he'd never talked in public before about his war experience," she says. "He was shy and modest, but deeply intelligent. And when he got up to speak, it was just dazzling."

Rita Nakashima Brock served as keynote speaker at Emory's recent symposium on moral injury, moral repair and moral leadership.

With a voice sometimes wavering, Yandell spoke of disillusionment — not with the U.S. military's ability to carry out missions, not with his brothers and sisters in arms. What had begun to erode for him was "my younger self's perception of good and evil," he explained. "That's the best way I could describe moral injury."

In Iraq, it was easy to believe they were liberating the poor, the weak and oppressed. On a daily basis, EOD technicians were cleaning streets of bombs, saving lives and property. "Of course that was the morally right action," he said. "I was one of the good guys— or so I thought…"

In hindsight, not only was it hard to recapture feelings of moral certainty, "I find it hard to even imagine what it felt like," he told the audience.

"What comes to mind is not the fact that we removed dangerous devices and saved lives. It's the fact that almost all those munitions and explosive materials were manufactured either in the Soviet Union or the United States long before they were used as IEDs planted on the streets of Baghdad. Would they have even been placed on the streets of Baghdad had the U.S. military not been present?"

The images that haunted him, he said, were those of Iraqi children, often clustered at an incidence response scene asking for candy. At the time, they made him angry. He had a mission to make things safer. They were in the way.

"Now, I find myself asking what does it mean to have a child consistently witness that explosive force and destruction — even if the destruction is serving to remove dangerous devices from their streets?"

In retrospect, Yandell saw the rightness and wrongness of war as inextricably bound. Was there anything about it that offered moral certainty?

"For me, the words 'good' and 'evil' have no place in the discussion about war," he explained. "The moment one can be labeled 'evil' and another 'good' is the moment people start dying."

Public speaking wasn't easy, but it helped him find a voice. He quickly became a regular speaker for the Soul Repair Center; it helped him untangle his own thoughts, make his own peace.

Increasingly, clergy and congregations were being asked to respond to issues of moral injury, and Yandell intended be a pastor. Brock suggested a detour. Go for a PhD, she urged. In the end, it could only make him a better pastor.

"Dr. Brock, are you telling me this because I'm a veteran?" he asked.

"No," she told him. "I'm saying this to you because you will make an amazing contribution."

Part 5: Naming moral injury

Ellen Ott Marshall, an associate professor of Christian ethics and conflict transformation in Emory’s Candler School of Theology, always looks forward to teaching what has become one of her favorite doctoral seminars: "Questions of War."

The topic fits well within the Graduate Division of Religion's concentration in religion, conflict and peacebuilding. Last year, the class included two students who happened to be military veterans, including Yandell. But the subject appealed to a broad range of scholars.

"Traditionally, the question of war is whether or not it is morally justified," Marshall explains. "But obviously, now there are many questions surrounding war. And increasingly, moral injury is a question students really want to explore."

Part of the appeal may be that being "injured in the soul," out of duty to an entity that betrays you, "is very recognizable to students, who are trying to sort through their own questions of conscience and duty," she says.

"Moral injury gives language to that. How do I think about duty and conscience? What happens when I do something out of duty that betrays my moral conscience? Who can be injured by whom?"

Emory PhD student Jenn Carlier recognized elements of moral injury within her research on addiction. Elizabeth Bounds, an associate professor of Christian ethics at Candler who studies moral and theological responses to conflict and violence, has examined ways incarcerated people — and those who guard them — may experience moral injury.

"There is discussion among scholars in religion about how broadly the concept can be used, especially in relation to the concept of trauma, which also can include the shattering of moral worlds," Bounds says.

In the 1980s, Robert Franklin, Emory's James T. and Berta R. Laney Professor of Moral Leadership, was first exposed to signs of moral injury while working with Vietnam veterans and law enforcement officers as a hospital chaplain on the south side of Chicago.

"I heard their confessions and cries of anguish long before I had the powerful vocabulary of moral injury to name it," he recalls.

Since then, the phenomenon has only grown. In fact, Franklin believes "we're now witnessing so many instances of people who feel their moral codes are being violated."

"In the military, in law enforcement and even the corporate and political arena, people may be ordered to do things they don't think are right and proper," he says. "So this phenomenon of being directed by people in authority to violate your own moral code is of growing societal interest — an eruption of discontent in the moral arena."

In response, Franklin has seen growing interest and research on the topic developing at Emory. "We have faculty in areas of ethics and theology and pastoral care who are very concerned about this unique species of injury and the possibilities for therapy and positive transformation," he says.

He's especially excited to find researchers investigating social dimensions of the phenomenon.

"They are not only looking at those in authority who violate an individual's moral conscience," he says, "but how we transform conflict itself, working on issues of reconciliation against groups that have been at odds or nations at war — from conflict resolution to conflict transformation."

Part 6: Looking to the future

Last fall, academics and students, military veterans and religious leaders gathered in Emory's Cannon Chapel as part of a three-day symposium on moral injury, moral repair and moral leadership.

"I feel like we're living in a moral injury moment," announces Brock, the keynote speaker, referring to today’s global and political climate. “I don’t think it’s an accident that we’re here.”

Clinical evidence now suggests spiritual practices, such as mindfulness, are helpful in addressing moral trauma, as are rituals, Brock says. Educating religious leaders to recognize moral injury can be critical. "Good chaplains can see things happening that a commander can't," she notes.

Later, Yandell joins her for a panel discussion. War is a mystery, he acknowledges, different for everyone who endures it.

While being exposed to sarin was the physical injury that garnered him the Purple Heart, he attributes his moral injury more to the cumulative effect of what he saw and did, the realities of working in a war zone.

Rita Nakashima Brock, Michael Yandell's mentor at Brite Divinity School, speaks with him on a panel at Emory's symposium on moral injury, moral repair and moral leadership.

In some ways, Yandell now sees his ability to experience moral injury as a sign of his own humanity — to accept dark feelings about "having done bad as a human" without self-loathing.

War wounded him, but it did not destroy him.

Yandell keeps few physical mementos of his military service — a uniform that hangs in a closet, a few grainy photos. He gave his Purple Heart to his sister. Beyond his scholarship, he doesn't talk much about the wounds of war.

But they remain. Spontaneous tears of rage on a trip to the grocery store. Difficulty looking someone in the eye when he's thanked for his service. Watching children scamper at his church in Decatur, he's reminded of Iraqi children begging for candy.

"The war lives in me, is a part of me," he acknowledges.

"In a sense, I don't think moral injury ever goes away. I will always live with this memory of war," he explains. "That's not something you heal from, but it is something that you integrate into your life."

And so, Yandell seeks his own peace. "If you can reckon with the experience and not pretend it's something it wasn't, then find something good you can do in service to others, I think that's a key to coping," he says.

The love of friends and family to see him through hard times. Having a life, a marriage. Engaging in meaningful work. It all helps.

"It doesn't change the past, but it eases the present," he says. "It reminds you that there is something left you can offer the world."

On the road to reconciliation, that's a solid start.