"School. What intelligent observations can I glean from the first two weeks? I pass through the labyrinths, corridors, see familiar faces, select and discard classes and activities, fluctuate between unquenchable curiosity and heavy, inert boredom."

These words, written just over 35 years ago, will feel familiar to most college students — far from home, starting a new academic year, "not having yet settled on the limits, and thus the form, that the new semester will take."

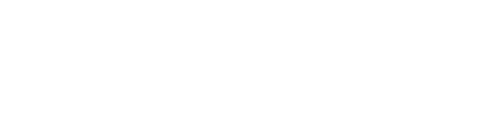

Their young author, writing to his girlfriend and pondering topics ranging from college classes to social class, could be any of us who ever wondered where we fit in the world. Except he went on to become the 44th president of the United States, the first African American to hold the highest office in the nation.

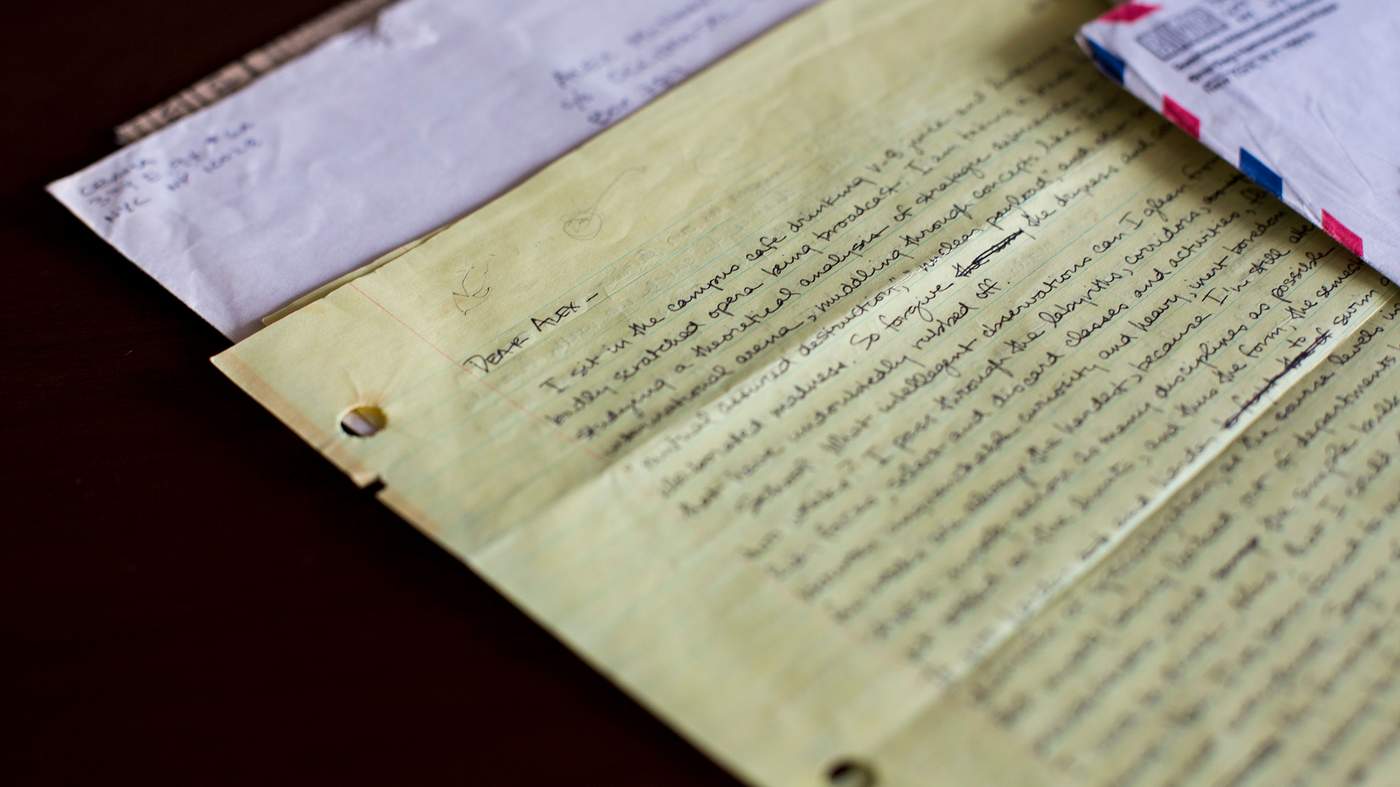

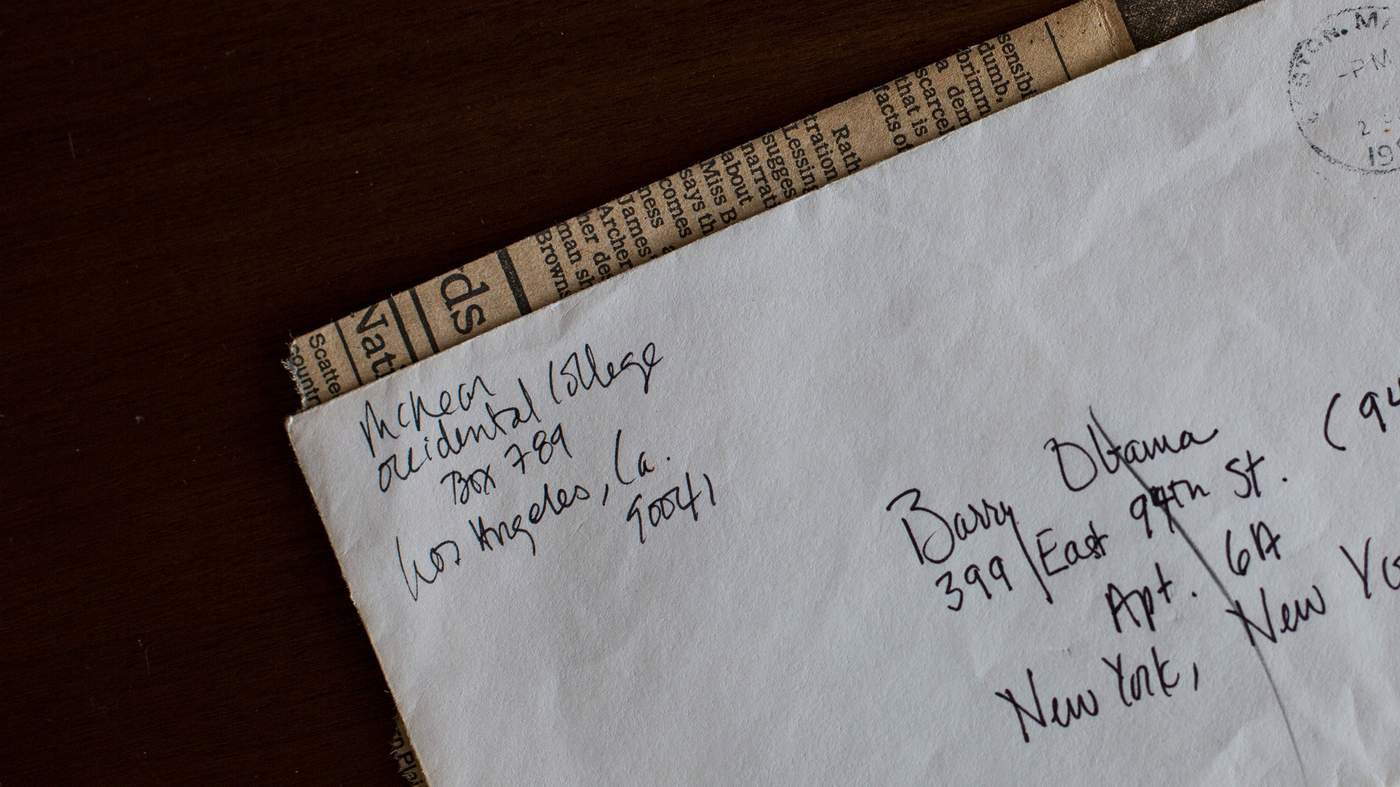

The series of letters written by Barack Obama to his then-girlfriend, Alexandra McNear, are now part of the collection of Emory's Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, where they are available to scholars and students by appointment. There will be an opportunity to view facsimiles of the letters on Friday, Oct. 20, from 2 t0 4 p.m. in the Woodruff Commons of the Rose Library.

Beautifully composed, the letters "reveal the search of a young man for meaning and identity," says Rosemary Magee, Rose Library director. "While intimate in a philosophical way, they reflect primarily a college student coming to terms with himself and others.

"In fact, they show the same kind of yearnings and issues that our own students face — and that students everywhere encounter," Magee explains. "Thus they will serve as sources of both inspiration and reassurance to people of all ages and backgrounds."

Spanning 1982 to 1984, the letters were written after Obama, who began his college career at California's Occidental College, transferred to Columbia University in New York City.

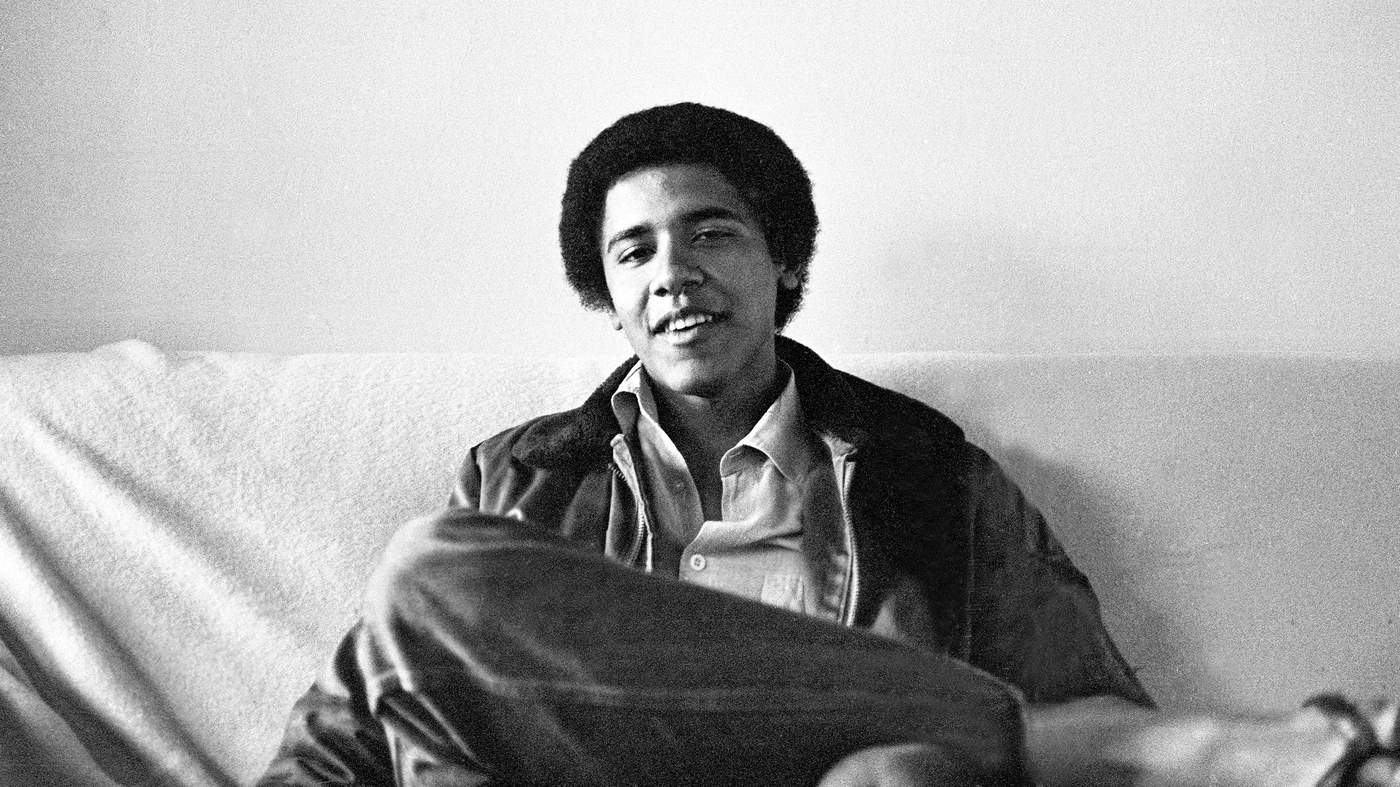

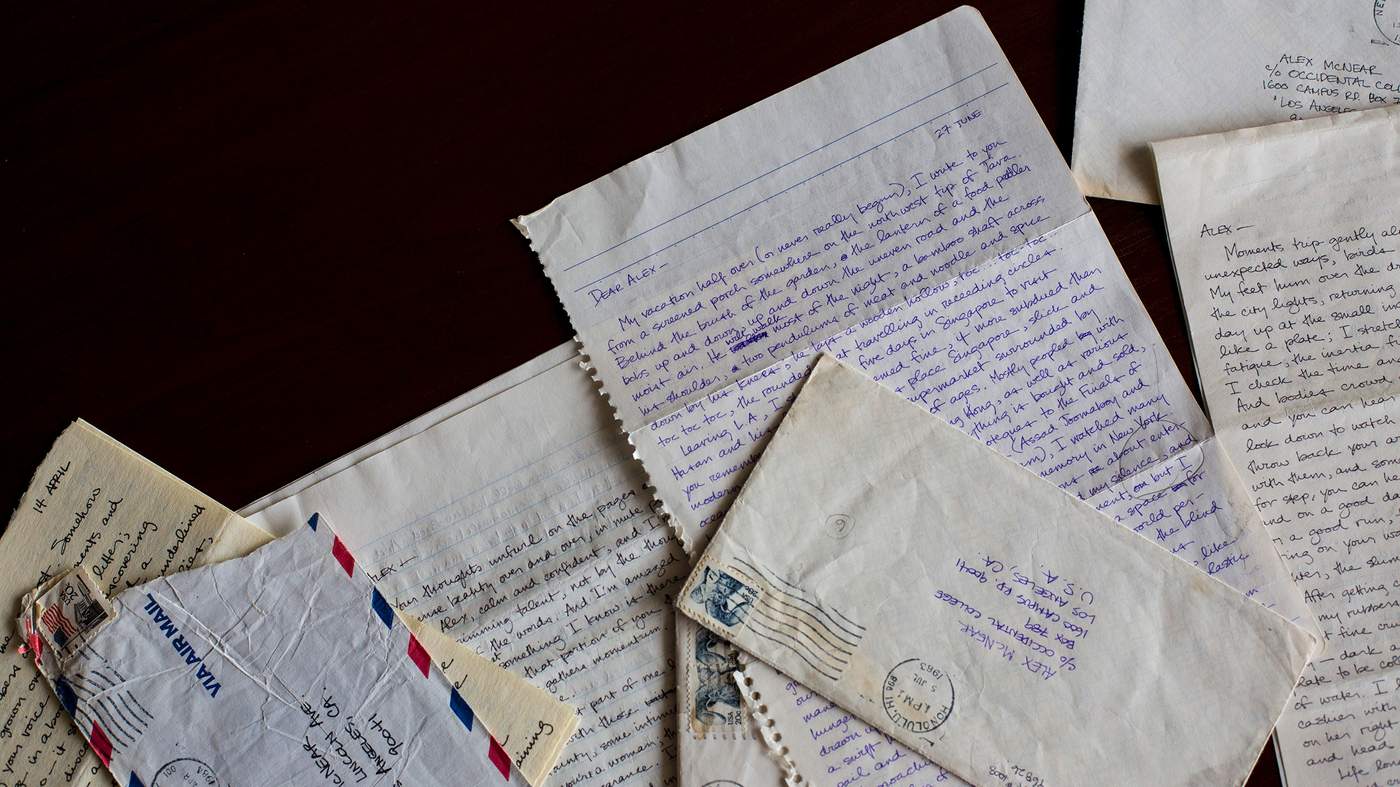

In page after page of neat script — written on lined yellow paper, typing paper, pages torn from spiral notebooks and even an index card — the future president poured out his thoughts and feelings to McNear, a fellow student from Occidental to whom he had grown even closer when she spent the summer of 1982 in New York.

The nine letters in Emory's collection pick up on Sept. 26, 1982, when both are back in classes at their respective schools on opposite coasts, and continue through April 14, 1984, when their romance has cooled to friendship and Obama has finished college and is working at Business International, "with everyone slapping my back" but no passion for the job.

They reference authors ranging from William Butler Yeats and T.S. Eliot to Virginia Woolf and June Jordan, and show a young man trying to make sense of the political and social structures that surround him and grappling with the most effective way to make the changes that he believes are needed.

"What is very striking about the letters is how they show President Obama's intellectual development," says Andra Gillespie, associate professor of political science and director of Emory's James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference. "You can see how intellectually curious he is, even in his early 20s.

"I think undergraduate students will benefit immensely from seeing how, as a young man, Obama internalized his studies and got the most out of a liberal arts education."

The letters join other materials in Emory's Rose Library to enrich research on African American history and culture, says Pellom McDaniels III, curator of African American collections for the Rose Library.

"From slavery to the civil rights movement, and now, to the first African American president of the United States, these collections provide tremendous insight into what can be described as a spiritual odyssey to wholeness," he says.

In the Sept. 26, 1982, letter — the first in the Emory collection and one of the longest — Obama writes from the campus café, where he is "drinking V8 juice and listening to a badly scratched opera being broadcast."

Obama had transferred to Columbia as a junior in 1981. Now starting his senior year, he explains how "it gets harder and harder to swim against the channels of specialization, as the course levels increase," and notes that his favorite class so far is a physics course for non-mathematicians (Obama majored in political science) that he is taking to fill a science requirement.

Yet he observes wryly that even this class doesn't truly offer a break from the difficult questions about the behavior of people and nations that fill most of his time.

"Thinking in purely scientific terms, and dealing with scales far removed from the human world, gives me a release and creative escape from the frustrations of studying men and their frequently dingy institutions," Obama writes, before adding, "Of course, the fact that the knowledge I absorb in the class facilitates nuclear war prevents a clean break."

He talks about friends coming to visit, but notes ruefully "how quickly the class lines are being drawn" with old friends moving into the roles that society seems to prescribe for them.

One college friend will soon marry and take over the family business, while a high school friend now manages a supermarket, racking up possessions like TVs and new cars.

"I must admit large dollops of envy for both groups, my American friends consuming their life in the comfortable mainstream, the foreign friends in the international business world," Obama tells McNear. "Caught without a class, a structure, or a tradition to support me, in a sense the choice to take a different path is made for me.

"The only way to assuage my feelings of isolation are to absorb all the traditions, classes, make them mine, me theirs. Taken separately, they're unacceptable and untenable."

Emblematic of the entire series of correspondence, he also takes time to respond point by point to a previous letter from McNear, who is struggling with her own understanding of herself and the world.

"I trust you know that I miss you, that my concern for you is as wide as the air, my confidence in you as deep as the sea, my love rich and plentiful," he pledges, before signing the missive "Love, Barack."

In the letters that follow, Obama seeks to relate to McNear as both boyfriend and scholar, connecting through words across the miles that separate them.

Writing next on Nov. 20, 1982, he struggles with "choice" — and whether he truly has choices in who he is and will be — attempting to explain further what he has meant by the word in past conversations with McNear.

"I use the word 'choice' as a convenient shorthand for the way my past resolves itself," he writes. "Not just my past, but the past of my ancestors, the planet, the universe."

The letters clearly show that for Obama, "writing is a form of discovery, a way of discovering himself and charting a future," Magee says. "He is looking to find his place and he doesn't neatly fit the categories that surround him, which is a concern to him, yet he also recognizes that it gives him a distinct perspective that he is grappling with."

Attempting to lay out his thoughts about power, he writes in depth about sex, class and race, and the relationships among them.

From his own thinking and books he's been reading, he expresses his concern about the role Western men have played in subjugating others, "the ideology they present is backed by a very real power; it's a symbiotic relationship that, in a limited time frame, can be said to 'work' for them."

Obama clearly relishes the back-and-forth conversation with McNear, the intellectual parry with someone who makes him question his own beliefs.

The challenge, he writes early in the Nov. 20 letter, "lies in forging a unity, mixing it up, constructing the truth to be found between the seams of individual lives. All of which requires breaking some sweat. Like a good basketball game. Or a fine dance. Or making love.

"We will talk long and deep, Alex," he promises,"and see what we can make of this."

And talk they do, in seven more letters over almost 18 months — written from New York, from "a screened porch somewhere on the northwest tip of Java," from times when Obama has just visited McNear, and finally, from when they have become friends who remain in touch less frequently.

In a missive from Feb. 10, 1983, Obama offers a detailed description of his daily routine of running and visiting a nearby Greek coffee shop — "My feet hum over the dry walks" — then ponders the concept of "resistance."

"I watch men and women pouring into the present mold, siphoned this and that way, and it worries me, the weight and momentum of these fluid lives sluiced into serving a distorted system," he writes, but notes that he "can see and taste the possibility of switching the gates, channeling the energy towards something of vitality and dignity."

With most people "busy keeping mouths fed and surroundings intact," Obama tells McNear, "it is left to the obsessed ones like us to make the alternatives more tangible, the contours of life's possibilities more defined, so that resistance and destruction arrive in the form of creation."

But there are also moments of levity within the deep discussions.

Two letters from April 1983 show the young Obama immersed in the details of university life, chafing a bit under the weight of "churning out the assignments" as he continues to ponder the bigger questions that fill his thoughts.

In an April 1 letter, he recounts trying to track down the person who has the papers "upon whom my graduation depends," as his "wicked imagination" spins out humorous worst-case scenarios: "She's a madwoman who lures unsuspecting undergraduate papers into her home and then burns them, or uses them to line the bottom of the gold finch cage. …

"But despite this mild anxiety, I stay in a piece, workin' my magic," Obama jokes.

He also reflects on uncertainty about his relationship with McNear as integral to his uncertainty about "everything I believe."

"I feel sunk in that long corridor between old values, actions, modes of thought, and those that I seek, that I'm working towards," he says.

Writing again April 27, he tries to engage with the "big questions" McNear has posed to him in letters and phone conversations, about her own worries and their relationship.

Obama writes of time they spent together at his friend Wahid's apartment: "A young black man with his arm behind his head, staring at the ceiling with moist eyes, and a young white woman resting her head on his arm, alone and facing the swirling expanse, outside the room, inside themselves, separate in the eye of the storm."

He worries whether he is coming across as "a blathering chump," yet concludes that he can't separate his questions about his own identity from larger questions and concerns about the world.

"I don't distinguish between struggling with the world and struggling with myself. … I enter a pact with other people, other forces in the world, that their problems are mine and mine are theirs. … The minute others imprint my senses, they become me and I must deal with them or else close part of myself off and make myself and the world smaller, lukewarm."

In closing, Obama notes that he plans to take a two-month vacation to Indonesia and Hawaii starting the next month, and adds that he will be in Los Angeles in late May, "so I can make more sense over dinner."

Obama's next note to McNear comes two months later, a month into his trip. Written June 27, 1983, the short letter reflects on how class and race are made even more complicated by national identities.

After seeing McNear in Los Angeles, he visits with his mother and sister, "who are doing well," in Java. Yet despite living in Indonesia as a young boy, Obama finds that he no longer fits there, either.

Obama's mother was born in Kansas, his father, in Kenya; the couple met while attending the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Obama was born Aug. 4, 1961, in Honolulu. His mother and father frequently lived apart before separating when Obama was two; in 1965, his mother married a man from Indonesia who was also a student at the University of Hawaii.

The family later moved to Indonesia, but at age 10, Obama moved back to Honolulu to live with his maternal grandparents.

"I can't speak the language well anymore," he tells McNear. "I'm treated with a mixture of puzzlement, deference and scorn because I'm American, my money and my plane ticket back to the U.S. overriding my blackness. I see old dim roads, rickety homes winding back towards the fields, old routes of mine, routes I no longer have access to."

His roots with McNear, too, feel less certain, as is the route their relationship will take.

"I think of you often, though I stay confused about my feelings," Obama writes. "It seems we will ever want what we cannot have; that's what binds us; that's what keeps us apart."

The next letter in Emory's collection, written Sept. 1, 1983, from Honolulu, shows Obama responding directly to a difficult letter from McNear that addressed their relationship.

"I am not so naïve as to believe that a distinct line exists between romantic love and the more quotidian, but perhaps finer bonds of friendship," he writes, "but I can feel the progression from one to the other (in my mind)."

Obama also gently mocks the tone and tenor of some of his earlier letters: "When I sit down to write, I no longer feel the need to bleed for brilliance on the page; I trust the strength of our relationship enough that I can show myself with curlers in my hair, my will sapped, my confidence shaken, a bit peevish perhaps, a bit dull."

Gillespie contrasts these passages to his more cerebral musings: "It is interesting to see Obama as a young romantic partner, especially in a relationship that predates his relationship with Michelle Obama.

"The letters that Emory has capture the arc of the end of a relationship," she says. "While there isn’t a Dear John/Jane letter here, you do see the aftermath of a breakup. It’s raw and very human."

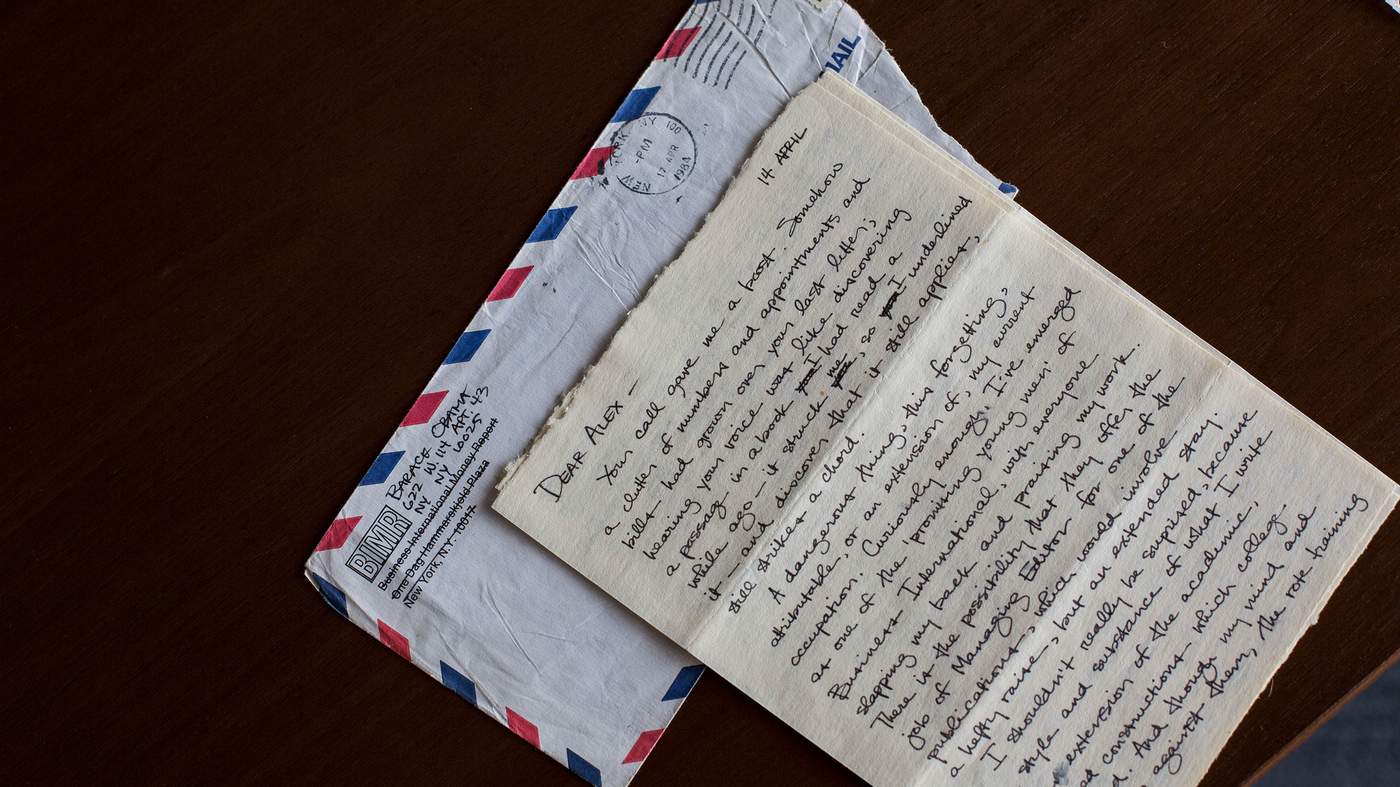

The final two letters in Emory's collection reflect a young man in transition — from school to work, from romance to friendship, and from theories about how to make change in the world to more practical thoughts of how he might apply them.

Back in New York City, Obama writes to McNear on Nov. 15, 1983, describing how he visited Wahid on Long Island, "spying on the damp A-frame life of suburbia," and how upon his return to the city, "Manhattan swallowed me without a sound."

Much of his time is spent on routine matters: "I have tried to tie down the stakes of life out of school, starting with employment and housing, before winter turns humorless." He is renting a room from a woman who is a dancer and taxicab driver, but suspects he may move; "jobs are a more ticklish problem."

"Salaries in the community organizations are too low to survive on right now, so I hope to work in some more conventional capacity for a year, allowing me to store up enough nuts to pursue those interests next," he says.

Money is a more immediate problem, too — "One week I can't pay postage to mail a resume and writing sample, the next I have to bounce a check to rent a typewriter" — so Obama takes a temporary job moving files from the Manhattan fire department to a new location.

Working alongside lower-income young people, elderly women and unemployed former students, he realizes that these workers have "a greater political perception" than he expected, and feels a particular affinity for the black and Latino workers, which he says "strengthened me in some important way."

"I feel lonely yet surefooted, and hope all goes well for you," he concludes.

The final letter in the collection comes more than four months later, on April 14, 1984, as Obama has taken a job at Business International and is absorbing the lessons of the corporate world. His writing is still lyrical and his thoughts still focused, but both are less abstract than in the earlier letters.

He notes how pleased he was to talk with McNear on the phone and tells her about his job, where he is somewhat bemused at his success: "Curiously enough, I've emerged as one of the 'promising young men' of Business International, with everyone slapping my back and praising my work," he says.

He adds that he has "cultivated strong bonds with the black women and their children in the company, who work as librarians, receptionists, etc.," while "the only black men are teen messengers."

"The resistance I wage does wear me down — because of the position, the best I can hope for is a draw, since I have no vehicle or forum to try to change things," he notes. "For this reason, I can't stay very much longer than a year. Thankfully, I don't yet feel like the job has dulled my senses or done irreparable damage to my values, although it has stalled their growth."

For Gillespie, whose upcoming book is about the Obama administration, the letters provide a glimpse of his future as well as insight into his past.

"Obama says things in his letters which foreshadow things that have become a part of his public biography," she explains.

"You can see how he's formulating his identity as a black man and a part of a black community. And he's a little proto-feminist, too. There are nice connections between his thoughts in these letters, and what he discusses in 'Dreams from My Father.'"

As the thoughts of a young person reflecting upon his place in the world, the letters are also in conversation with other Rose Library materials, Magee notes.

“In this way, they connect with the poetry of Seamus Heaney and Natasha Trethewey; the historical presence of public figures like Sam Nunn; and the creative, intellectual energy of Jack Kerouac, Alice Walker and Flannery O’Connor," she says. "They invite people of all backgrounds and disciplines into the conversation.”

Late in the final letter, Obama reflects on his "political reading/spectating":

"My ideas aren't as crystallized as they were while in school, but they have an immediacy and weight that may be more useful if and when I'm less observer and more participant."

And, of course, what a participant he became.