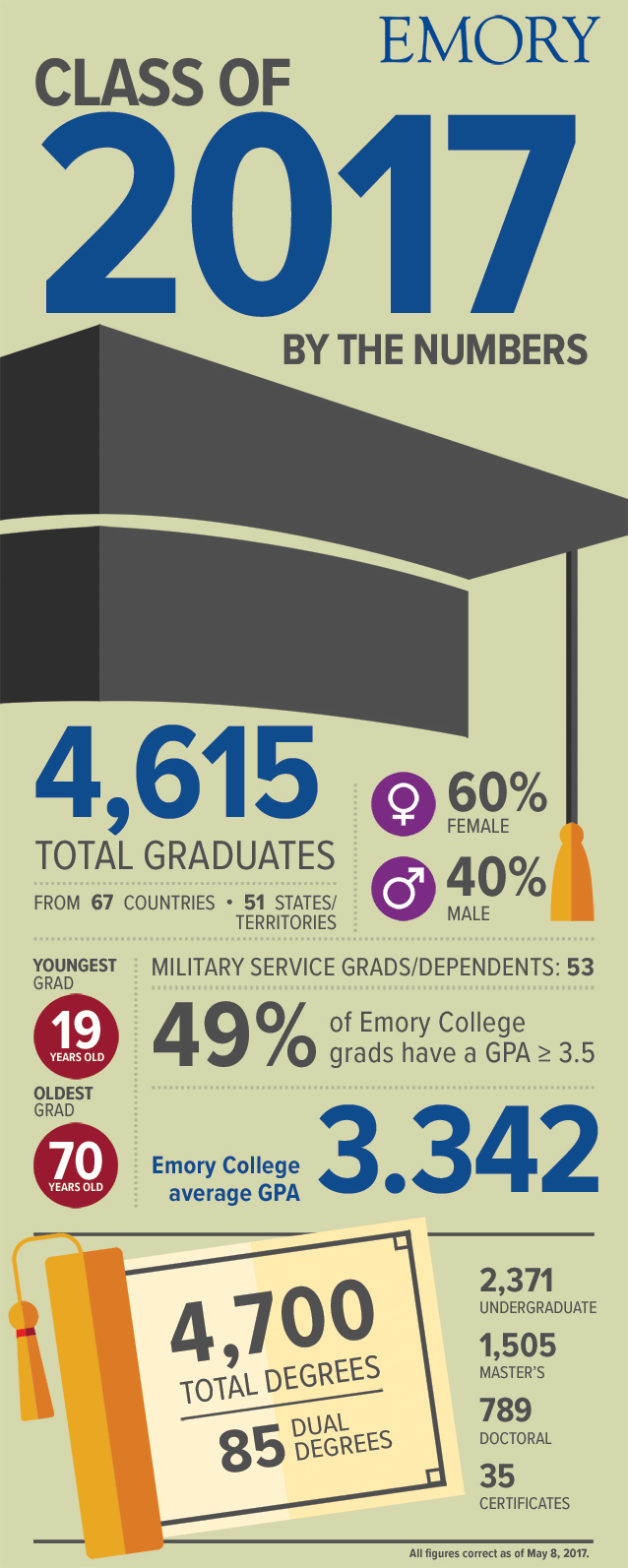

In her keynote, Trethewey acknowledged similarities to this year’s graduates, who collectively earned a record-setting 4,700 degrees.

“Like you, I am moving on from a place I have known and loved for years,” she said. “I have made friendships and an intellectual community that I will cherish the rest of my life. For me, as for you, it is time to face new challenges, to continue to grow.”

After 15 years at Emory, Trethewey, the Robert W. Woodruff Professor of English and Creative Writing and director of Emory’s Creative Writing Program, will join Northwestern University’s English department this fall.

Surveying the expansive sea of graduates, Trethewey acknowledged there was a time that she could never have imagined returning to the Atlanta community, “which for me is a place of personal trauma and great loss.”

In 1985, Trethewey’s mother was murdered by her stepfather, “just over five miles away from where I now stand,” she explained. “When I left … I thought I could simply run away from it and distance myself from that history that bound me to this place.”

“What drew me back was Emory,” she said. “Being here has been more than just a job for me — it has transformed me.”

In her keynote, Trethewey told graduates that she chose to come to Emory for many of the reasons they did, including an environment that nourished “rigorous intellectual pursuits and deeply enriching and transformative creative and artistic ones.”

But folded into the experience was the challenge of confronting uncomfortable truths. No matter how hard she tried to avoid it, “the past kept finding me, inserting itself into my daily life,” Trethewey said.

While jogging through Decatur Cemetery, Trethewey recalled seeing a section devoted to fallen Confederate soldiers. At the time, she was writing “Native Guard,” which tells the story of an all-black regiment in the Union Army, composed largely of former slaves, who had guarded Confederate prisoners of war.

Those Union soldiers had been largely forgotten, “erased from the monumental landscape, buried in the recesses of our collective history,” Trethewey explained.

The encounter inspired her to write a poem about the Confederate soldiers, “but what came out instead was a poem about the day I buried my mother,” she said.

The poem included the line: “I wander now among names of the dead: My mother’s name, stone pillow for my head,” which was “a beautiful lie,” said Trethewey.

Reluctant to memorialize the name of her mother’s murderer, she had never ordered a headstone. “It was a failure of imagination,” she said, admitting she hadn’t thought to use her mother’s maiden name on the headstone.

But it was a failure that prodded a critical self-examination — a goal that Trethewey urged Emory's newest graduates to also pursue.

In today's tumultuous times, Tretheway told graduates, it is more important than ever for them to move forward as critical thinkers.

“Don’t be ignorant of history, fooled by the false narratives of those who lie about the past for their own gains,” she said. “Don’t squander the years you spent here by becoming complacent as a reader and not challenging your own assumptions, as well as the unsubstantiated claims of others.

“Ask questions,” she said. “Remember the primacy of evidence.”

She closed her address by quoting a line from a poem by her late father, poet Eric Trethewey: "Why are we not better than we are?"

"By asking that question of our individual and collective selves … we can rise above the empty rhetoric of self-interest and self-aggrandizement that characterizes our troubled national moment," Trethewey concluded, "and make of ourselves, the way we lead our lives, poetry."